An

Introduction to

Aikido

Beginning the Journey

Table of Contents

Aikido and Combat Effectiveness. 3

Training the Mind in Aikido. 5

A Personal Note

Much of this document was originally The Aikido Primer by Eric Sotnak (http://home.neo.lrun.com/sotnak/primer.html). The following is Mr. Sotnak’s introduction:

Introductory notice:

Please feel free to copy and distribute this primer to fellow aikidoists, non-aikidoists, friends, enemies, or people who just need something to put them to sleep. Should you wish to customize it for your own dojo, you may do so, but do, please, endeavor to make any changes commensurate with the overall spirit of the thing. If you want to avoid being blamed for any mistakes in this document or for the content, you could include this introductory notice or attach my name somewhere else within the document. I hereby disclaim any responsibility for the content or for errors within any versions of this document not modified by myself.

I have adopted the Western convention for personal names in this document, i.e., first name first, family name second.

This version is dated September 1999.

Most of the remainder of this document was culled from resources on the Internet. Particular thanks to Jun Akiyama for his wonderful website, AikiWeb (http://www.aikiweb.com). All photographs herein contained are the copyrighted property of their respective copyright holders.

And there is a very small part of this document that comes from my personal experience as an Aikidoka. I do plan to update/rewrite this document frequently to include more of my personal observations. I also plan to eventually add diagrams of techniques.

Good luck, and may you find peace and happiness on your journey.

Steven M. Fellwock

Lincoln, Nebraska

September 2000

An Introduction to Aikido

Introduction

Although Aikido is a

relatively recent innovation within the world of martial arts, it is heir to a

rich cultural and philosophical background. Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969)

created Aikido in Japan. Before creating Aikido, Ueshiba trained extensively

in several varieties of jujitsu, as well as sword and spear fighting. Ueshiba

also immersed himself in religious studies and developed an ideology devoted

to universal socio-political harmony. Incorporating these principles into his

martial art, Ueshiba developed many aspects of Aikido in concert with his

philosophical and religious ideology.

Although Aikido is a

relatively recent innovation within the world of martial arts, it is heir to a

rich cultural and philosophical background. Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969)

created Aikido in Japan. Before creating Aikido, Ueshiba trained extensively

in several varieties of jujitsu, as well as sword and spear fighting. Ueshiba

also immersed himself in religious studies and developed an ideology devoted

to universal socio-political harmony. Incorporating these principles into his

martial art, Ueshiba developed many aspects of Aikido in concert with his

philosophical and religious ideology.

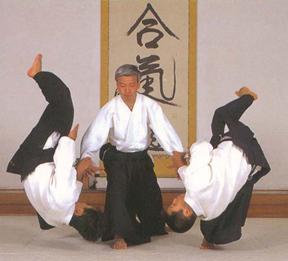

Aikido is not primarily a system of combat, but rather a means of self-cultivation and improvement. Aikido has no tournaments, competitions, contests, or “sparring.” Instead, all Aikido techniques are learned cooperatively at a pace commensurate with the abilities of each trainee. According to the founder, the goal of Aikido is not the defeat of others, but the defeat of the negative characteristics which inhabit one’s own mind and inhibit its functioning.

At the same time, the potential of Aikido as a means of self-defense should not be ignored. One reason for the prohibition of competition in Aikido is that many Aikido techniques would have to be excluded because of their potential to cause serious injury. By training cooperatively, even potentially lethal techniques can be practiced without substantial risk.

It must be emphasized that there are no shortcuts to proficiency in Aikido (or in anything else, for that matter). Consequently, attaining proficiency in Aikido is simply a matter of sustained and dedicated training. No one becomes an expert in just a few months or years.

An Introduction to Aikido

History of Aikido

Aikido’s

founder, Morihei Ueshiba, was born in Japan on December 14, 1883. As a boy, he

often saw local thugs beat up his father for political reasons. He set out to

make himself strong so that he could take revenge. He devoted himself to hard

physical conditioning and eventually to the practice of martial arts,

receiving certificates of mastery in several styles of jujitsu, fencing, and

spear fighting. In spite of his impressive physical and martial capabilities,

however, he felt very dissatisfied. He began delving into religions in hopes

of finding a deeper significance to life, all the while continuing to pursue

his studies of budo, or the martial arts. By combining his martial training

with his religious and political ideologies, he created the modern martial art

of Aikido. Ueshiba decided on the name “Aikido” in 1942 (before that he

called his martial art “aikibudo” and “aikinomichi”).

Aikido’s

founder, Morihei Ueshiba, was born in Japan on December 14, 1883. As a boy, he

often saw local thugs beat up his father for political reasons. He set out to

make himself strong so that he could take revenge. He devoted himself to hard

physical conditioning and eventually to the practice of martial arts,

receiving certificates of mastery in several styles of jujitsu, fencing, and

spear fighting. In spite of his impressive physical and martial capabilities,

however, he felt very dissatisfied. He began delving into religions in hopes

of finding a deeper significance to life, all the while continuing to pursue

his studies of budo, or the martial arts. By combining his martial training

with his religious and political ideologies, he created the modern martial art

of Aikido. Ueshiba decided on the name “Aikido” in 1942 (before that he

called his martial art “aikibudo” and “aikinomichi”).

On the technical side, Aikido is rooted in several styles of jujitsu (from which modern judo is also derived), in particular daitoryu-(aiki)jujitsu, as well as sword and spear fighting arts. Oversimplifying somewhat, we may say that Aikido takes the joint locks and throws from jujitsu and combines them with the body movements of sword and spear fighting. However, we must also realize that many Aikido techniques are the result of Master Ueshiba’s own innovation.

On the religious side, Ueshiba was a devotee of one of Japan’s so-called “new religions,” Omoto Kyo. Omoto Kyo was (and is) part neo-Shintoism, and part socio-political idealism. One goal of Omoto Kyo has been the unification of all humanity in a single “heavenly kingdom on earth” where all religions would be united under the banner of Omoto Kyo. It is impossible sufficiently to understand many of O-Sensei’s writings and sayings without keeping the influence of Omoto Kyo firmly in mind.

Despite what many people think or claim, there is no unified philosophy of Aikido. What there is, instead, is a disorganized and only partially coherent collection of religious, ethical, and metaphysical beliefs which are only more or less shared by Aikidoka, and which are either transmitted by word of mouth or found in scattered publications about Aikido.

Some examples: “Aikido is not a way to fight with or defeat enemies; it is a way to reconcile the world and make all human beings one family.” “The essence of Aikido is the cultivation of ki [a vital force, internal power, mental/spiritual energy].” “The secret of Aikido is to become one with the universe.” “Aikido is primarily a way to achieve physical and psychological self-mastery.” “The body is the concrete unification of the physical and spiritual created by the universe.” And so forth.

At the core of almost all philosophical interpretations of Aikido, however, we may identify at least two fundamental threads: (1) A commitment to peaceful resolution of conflict whenever possible. (2) A commitment to self-improvement through Aikido training.

Training

Aikido practice begins the moment you enter the dojo! Trainees ought to endeavor to observe proper etiquette at all times. It is proper to bow when entering and leaving the dojo, and when coming onto and leaving the mat. Approximately 3-5 minutes before the official start of class, trainees should line up and sit quietly in seiza (kneeling) or with legs crossed.

The only way to advance in Aikido is through regular and continued training. Attendance is not mandatory, but keep in mind that in order to improve in Aikido, one probably needs to practice at least twice a week. In addition, insofar as Aikido provides a way of cultivating self-discipline, such self-discipline begins with regular attendance.

Your training is your own responsibility. No one is going to take you by the hand and lead you to proficiency in Aikido. In particular, it is not the responsibility of the instructor or senior students to see to it that you learn anything. Part of Aikido training is learning to observe effectively. Before asking for help, therefore, you should first try to figure the technique out for yourself by watching others.

Aikido training encompasses more than techniques. Training in Aikido includes observation and modification of both physical and psychological patterns of thought and behavior. In particular, you must pay attention to the way you react to various sorts of circumstances. Thus part of Aikido training is the cultivation of (self-)awareness.

The following point is very important: Aikido training is a cooperative, not competitive, enterprise. Techniques are learned through training with a partner, not an opponent. You must always be careful to practice in such a way that you temper the speed and power of your technique in accordance with the abilities of your partner. Your partner is lending his/her body to you for you to practice on – it is not unreasonable to expect you to take good care of what has been lent you.

Aikido training may sometimes be very frustrating. Learning to cope with this frustration is also a part of Aikido training. Practitioners need to observe themselves in order to determine the root of their frustration and dissatisfaction with their progress. Sometimes the cause is a tendency to compare oneself too closely with other trainees. Notice, however, that this is itself a form of competition. It is a fine thing to admire the talents of others and to strive to emulate them, but care should be taken not to allow comparisons with others to foster resentment, or excessive self-criticism.

If at any time during Aikido training you become too tired to continue or if an injury prevents you from performing some Aikido movement or technique, it is permissible to bow out of practice temporarily until you feel able to continue. If you must leave the mat, ask the instructor for permission.

Although Aikido is best learned with a partner, there are a number of ways to pursue solo training in Aikido. First, one can practice solo forms (kata) with a jo or bokken. Second, one can “shadow” techniques by simply performing the movements of Aikido techniques with an imaginary partner. Even purely mental rehearsal of Aikido techniques can serve as an effective form of solo training.

It is advisable to practice a minimum of two hours per week in order to progress in Aikido.

Aikido and Combat Effectiveness

Many

practitioners of Aikido (from beginners to advanced students) have concerns

about the practical self-defense value of Aikido as a martial art. The attacks

as practiced in the dojo are frequently unrealistic and may be delivered

without much speed or power. The concerns here are legitimate, but may,

perhaps, be redressed.

Many

practitioners of Aikido (from beginners to advanced students) have concerns

about the practical self-defense value of Aikido as a martial art. The attacks

as practiced in the dojo are frequently unrealistic and may be delivered

without much speed or power. The concerns here are legitimate, but may,

perhaps, be redressed.

In the first place, it is important to realize that Aikido techniques are usually practiced against stylized and idealized attacks. This makes it easier for students to learn the general patterns of Aikido movement. As students become more advanced, the speed and power of attacks should be increased, and students should learn to adapt the basic strategies of Aikido movement to a broader variety of attacks.

Many Aikido techniques cannot be performed effectively without the concomitant application of atemi (a strike delivered to the attacker for the purpose of facilitating the subsequent application of the technique). For safety’s sake, atemi is often omitted during practice. It is important, however, to study atemi carefully and perhaps to devote some time to practicing application of atemi so that one will be able to apply it effectively when necessary.

Aikido is sometimes held up for comparison to other martial arts, and Aikido students are frequently curious about how well a person trained in Aikido would stand up against someone of comparable size and strength who has trained in another martial art such as karate, judo, ju jutsu, or boxing. It is natural to hope that the martial art one has chosen to train in has effective combat applications. However, it is also important to realize that the founder of Aikido deliberately chose to develop his martial art into something other than the most deadly fighting art on the planet, and it may very well be true that other martial arts are more combat effective than Aikido. This is not to say that Aikido techniques cannot be combat effective – there are numerous practitioners of Aikido who have applied Aikido techniques successfully to defend themselves in a variety of life-threatening situations. No martial art can guarantee victory in every possible circumstance. All martial arts, including Aikido, consist in sets of strategies for managing conflict. The best anyone can hope for from their martial arts training is that the odds of managing the conflict successfully are improved. There are many different types of conflict, and many different parameters that may define a conflict. Some martial arts may be better suited to some types of conflict than others. Aikido may be ill suited to conflicts involving deliberate provocation of an adversary to fight. While there are some who view this as a shortcoming or a liability, there are others who see this as demonstrating the foolhardiness of provoking fights.

Since conflicts are not restricted to situations that result in physical combat, it may be that a martial art which encodes strategies for managing other types of conflict will serve its practitioners better in their daily lives than a more combat-oriented art. Many teachers of Aikido treat it as just such a martial art. One is more commonly confronted with conflicts involving coworkers, significant others, or family members than with assailants bent on all-out physical violence. Also, even where physical violence is a genuine danger, many people seek strategies for dealing with such situations, which do not require doing injury. For example, someone working with mentally disturbed individuals may find it less than ideal to respond to aggression by knocking the individual to the ground and pummeling him or her into submission. Many people find that Aikido is an effective martial art for dealing with situations similar to this.

In the final analysis, each person must decide individually whether or not Aikido is suited to his or her needs, interests, and goals.

Weapons Training

Some

dojo hold classes which are devoted almost exclusively to training with to jo

(staff), tanto (knife), and bokken (sword); the three principal weapons used

in Aikido. However, since the goal of Aikido is not primarily to learn how to

use weapons, trainees are advised to attend a minimum of two non-weapons

classes per week if they plan to attend weapons classes.

Some

dojo hold classes which are devoted almost exclusively to training with to jo

(staff), tanto (knife), and bokken (sword); the three principal weapons used

in Aikido. However, since the goal of Aikido is not primarily to learn how to

use weapons, trainees are advised to attend a minimum of two non-weapons

classes per week if they plan to attend weapons classes.

There are several reasons for weapons training in Aikido. First, many Aikido movements are derived from classical weapons arts. There is thus a historical rationale for learning weapons movements. For example, all striking attacks in Aikido are derived from sword strikes. Because of this, empty-handed striking techniques in Aikido appear very inefficient and lacking in speed and power, especially if one has trained in a striking art such as karate or boxing.

Second, weapons training is helpful for learning proper ma ai, or distancing. Repeatedly moving in and out of the striking range of a weapon fosters an intuitive sense of distance and timing – something which is crucial to empty-hand training as well.

Third, many advanced Aikido techniques involve defenses against weapons. In order to ensure that such techniques can be practiced safely, it is important for students to know how to attack properly with weapons, and to defend against such attacks.

Fourth, there are often important principles of Aikido movement and technique that may be profitably demonstrated by the use of weapons.

Fifth, training in weapons kata is a way of facilitating understanding of general principles of Aikido movement.

Sixth, weapons training can add an element of intensity to Aikido practice, especially in practicing defenses against weapons attacks.

Seventh, training with weapons provides Aikidoka with an opportunity to develop a kind of responsiveness and sensitivity to the movements and actions of others within a format that is usually highly structured. In addition, it is often easier to discard competitive mindsets when engaged in weapons training, making it easier to focus on cognitive development.

Finally, weapons training is an excellent way to learn principles governing lines of attack and defense. All Aikido techniques begin with the defender moving off the line of attack and then creating a new line (often a non-straight line) for application of an Aikido technique.

About Bowing

It is common for

people to ask about the practice of bowing in Aikido. In particular, many

people are concerned that bowing may have some religious significance. It does

not. In Western culture, it is considered proper to shake hands when greeting

someone for the first time, to say “please” when making a request, and to

say “thank you” to express gratitude. In Japanese culture, bowing (at

least partly) may fulfill all these functions. Bear in mind, too, that in

European society only a few hundred years ago a courtly bow was a conventional

form of greeting.

It is common for

people to ask about the practice of bowing in Aikido. In particular, many

people are concerned that bowing may have some religious significance. It does

not. In Western culture, it is considered proper to shake hands when greeting

someone for the first time, to say “please” when making a request, and to

say “thank you” to express gratitude. In Japanese culture, bowing (at

least partly) may fulfill all these functions. Bear in mind, too, that in

European society only a few hundred years ago a courtly bow was a conventional

form of greeting.

Incorporating this particular aspect of Japanese culture into our Aikido practice serves several purposes:

- It inculcates a familiarity with an important aspect of Japanese culture in Aikido practitioners. This is especially important for anyone who may wish, at some time, to travel to Japan to practice Aikido. There is also a case to be made for simply broadening one’s cultural horizons.

- Bowing may be an expression of respect. As such, it indicates an open-minded attitude and a willingness to learn from one’s teachers and fellow students.

- Bowing to a partner may serve to remind you that your partner is a person – not a practice dummy. Always train within the limits of your partner’s abilities.

The initial bow, which signifies the beginning of formal practice, is much like a “ready, begin,” uttered at the beginning of an examination. So long as class is in session, you should behave in accordance with certain standards of deportment. Aikido class should be somewhat like a world unto itself. While in this “world,” your attention should be focused on the practice of Aikido. Bowing out is like signaling a return to the “ordinary” world.

When bowing either to the instructor at the beginning of practice or to one’s partner at the beginning of a technique it is considered proper to say “onegai shimasu” (lit. “I request a favor”) and when bowing either to the instructor at the end of class or to one’s partner at the end of a technique it is considered proper to say “domo arigato gozaimashita” (“thank you”).

Training the Mind in Aikido

The founder (Morihei Ueshiba) intended Aikido to be far more than a system of techniques for self-defense. His intention was to fuse his martial art to a set of ethical, social, and dispositional ideals. Ueshiba hoped that by training in Aikido, people would perfect themselves spiritually as well as physically. It is not immediately obvious, however, just how practicing Aikido is supposed to result in any spiritual (= psycho-physical) transformation. Furthermore, many other arts have claimed to be vehicles for carrying their practitioners to enlightenment or psychophysical transformation. We may legitimately wonder, then, whether, or how, Aikido differs from other arts in respect of transformative effect.

It should be clear that any transformative power of Aikido, if such exists at all, cannot reside in the performance of physical techniques alone. Rather, if Aikido is to provide a vehicle for self-improvement and psychophysical transformation along the lines envisioned by the founder, the practitioner of Aikido must adopt certain attitudes toward Aikido training and must strive to cultivate certain sorts of cognitive dispositions.

Classically, those arts, which claim to provide a transformative framework for their practitioners, are rooted in religious and philosophical traditions such as Buddhism and Taoism (the influence of Shinto on Japanese arts is usually comparatively small). In Japan, Zen Buddhism exercised the strongest influence on the development of transformative arts. Although Morihei Ueshiba was far less influenced by Taoism and Zen than by the “new religion,” Omoto Kyo, it is certainly possible to incorporate aspects of Zen and Taoist philosophy and practice into Aikido. Moreover, Omoto Kyo is largely rooted in a complex structure of neo-Shinto mystical concepts and beliefs. It would be wildly implausible to suppose that adoption of this structure is a necessary condition for psychophysical transformation through Aikido.

So far as the incorporation of Zen and Taoist practices and philosophies into Aikido is concerned, psychophysical transformation through the practice of Aikido will be little different from psychophysical transformation through the practice of arts such as karate, kyudo, and tea ceremony. All these arts have in common the goal of instilling in their practitioners cognitive equanimity, spontaneity of action/response, and receptivity to the character of things just as they are (shinnyo). The primary means for producing these sorts of dispositions in trainees is a two-fold focus on repetition of the fundamental movements and positions of the art, and on preserving mindfulness in practice.

The fact that Aikido training is always cooperative provides another locus for construing personal transformation through Aikido. Cooperative training facilitates the abandonment of a competitive mind-set that reinforces the perception of self-other dichotomies. Cooperative training also instills a regard for the safety and well being of one’s partner. This attitude of concern for others is then to be extended to other situations than the practice of Aikido. In other words, the cooperative framework for Aikido practice is supposed to translate directly into a framework for ethical behavior in one’s daily life.

Furthermore, it should be clear that if personal transformation is possible through Aikido training, it is not an automatic process. This should be apparent by noticing the fact that there are Aikido practitioners with many years of experience who still commit both moral and legal infractions. Technical proficiency and broad experience in the martial arts is by no means a guarantee of ethical or personal advancement. This fact often comes as a great disappointment to students of Aikido, especially if they should discover that their own instructors still suffer from a variety of shortcomings. In fact, however, this itself constitutes a valuable lesson: Technical proficiency is an easier goal to attain than that of personal improvement. Although both of these goals may require a lifetime of commitment, it is considerably easier to make the sort of sacrifices and efforts required for technical proficiency than it is to make the sacrifices and efforts required for substantive personal transformation and improvement.

The path to self-improvement and personal transformation must begin somewhere, however. Perhaps the most important (and easily forgotten) starting point for both students and teachers of Aikido is to bear constantly in mind that the people one is training with are one and all human beings like oneself, each with a unique perspective, and capable of feeling pain, frustration and happiness, and each with his or her own goals of training.

If one takes seriously the notion that part of one’s Aikido training should aim towards self-improvement, one may sometimes have to consider how one will be viewed by others. Someone may have superb technical ability and yet be viewed by others as a self-centered and inconsiderate bully.

A Note on Ki

The

concept of ki is one of the most difficult associated with the

philosophy and practice of Aikido. Since the word “Aikido” means

something like “the way of harmony with ki,” it is hardly surprising that

many Aikidoka are interested in understanding just what ki is supposed to be.

Etymologically, the word “ki” derives from the Chinese “chi.”

In Chinese philosophy, chi was a concept invoked to differentiate

living from non-living things. But as Chinese philosophy developed, the

concept of chi took on a wider range of meanings and interpretations.

On some views, chi was held to be the most basic explanatory material

principle – the metaphysical “energy” out of which all things were made.

The differences between things depended not on some things having chi

and others not, but rather on a principle (li, Japanese = ri) which

determined how the chi was organized and functioned (the view here

bears some similarity to the ancient Greek matter-form metaphysic).

The

concept of ki is one of the most difficult associated with the

philosophy and practice of Aikido. Since the word “Aikido” means

something like “the way of harmony with ki,” it is hardly surprising that

many Aikidoka are interested in understanding just what ki is supposed to be.

Etymologically, the word “ki” derives from the Chinese “chi.”

In Chinese philosophy, chi was a concept invoked to differentiate

living from non-living things. But as Chinese philosophy developed, the

concept of chi took on a wider range of meanings and interpretations.

On some views, chi was held to be the most basic explanatory material

principle – the metaphysical “energy” out of which all things were made.

The differences between things depended not on some things having chi

and others not, but rather on a principle (li, Japanese = ri) which

determined how the chi was organized and functioned (the view here

bears some similarity to the ancient Greek matter-form metaphysic).

Modern Aikidoka are less concerned with the historiography of the concept of ki than with the question of whether or not the term “ki” denotes anything real, and, if so, just what it does denote. There have been some attempts to demonstrate the objective existence of ki as a kind of “energy” or “stuff” that flows within the body (especially along certain channels, called “meridians”). So far, however, there are no reputable studies that conclusively demonstrate the existence of ki. Traditional Chinese medicine appeals to ki/chi as a theoretical entity, and some therapies based on this framework have been shown to produce more positive benefit than placebo, but it is entirely possible that the success of such therapies is better explained in ways other than supposing the truth of ki/chi theory. Many people claim that certain forms of exercise or concentration enable them to feel ki flowing through their bodies. Since such reports are subjective, they cannot constitute objective evidence for ki as “stuff.” Nor do anecdotal accounts of therapeutic effects of various ki practices constitute evidence for the objective existence of ki – anecdotal evidence does not have the same evidential status as evidence resulting from reputable double-blind experiments involving strict controls. Again, it may be that ki does exist as an objective phenomenon, but reliable evidence to support such a view is so far lacking.

There are a number of Aikidoka who claim to be able to demonstrate the (objective) existence of ki by performing various sorts of feats. One such feat, which is very popular, is the so-called “unbendable arm.” In this exercise, one person extends her arm while another person tries to bend the arm. First, she makes a fist and tightens the muscles in her arm. The other person is usually able to bend the arm. Next, she relaxes her arm (but leaves it extended) and “extends ki” (since “extending ki” is not something most newcomers to Aikido know precisely how to do, is often simply advised to think of her arm as a fire-hose gushing water, or some such similar metaphor). This time, the other person finds it far more difficult to bend the arm. The conclusion is supposed to be that it is the force/activity of ki that accounts for the difference. However, there are alternative explanations expressible within the vocabulary or scope of physics (or, perhaps, psychology) that are fully capable of accounting for the phenomenon here (subtle changes in body positioning, for example). In addition, the fact that it is difficult to filter out the biases and expectations of the participants in such demonstrations makes it all the more questionable whether they provide reliable evidence for the objective existence of ki.

Not all Aikidoka believe that ki is a kind of “stuff” or energy. For some Aikidoka, ki is an expedient concept – a blanket-concept that covers intentions, momentum, will, and attention. If one eschews the view that ki is an energy that can literally be extended, to extend ki is to adopt a physically and psychologically positive bearing. This maximizes the efficiency and adaptability of one’s movement, resulting in stronger technique and a feeling of affirmation both of oneself and one’s partner.

Irrespective of whether one chooses to take a realist or an anti-realist stance with respect to the objective existence of ki, there can be little doubt that there is more to Aikido than the mere physical manipulation of another person’s body. Aikido requires sensitivity to such diverse variables as timing, momentum, balance, the speed and power of an attack, and especially to the psychological state of one’s partner (or of an attacker).

In addition, to the extent that Aikido is not a system for gaining physical control over others, but rather a vehicle for self-improvement (or even enlightenment [see satori]), there can be little doubt that cultivation of a positive physical and psychological bearing is an important part of Aikido. Again, one may or may not wish to describe the cultivation of this positive bearing in terms of ki.

Ranking in Aikido

Policies governing rank promotions may vary, sometimes dramatically, from one Aikido dojo or organization to another. According to the standard set by the International Aikido Federation (IAF) and the United States Aikido Federation (USAF), there are 6 ranks below black belt. These ranks are called kyu ranks. In the IAF and USAF, colored belts do not usually distinguish kyu ranks. Other organizations (and some individual dojo) may use some system of colored belts to signify kyu ranks, however. There are a growing number of Aikido organizations and each has its own set of standards for ranking.

Eligibility for testing depends primarily (though not exclusively) upon accumulation of practice hours. Other relevant factors may include a trainee’s attitude with respect to others, regularity of attendance, and, in some organizations, contribution to the maintenance of the dojo or dissemination of Aikido.

Whatever the criteria for rank promotion, it is important to keep in mind that rank promotion does not necessarily translate into ability. The most important accomplishments in Aikido or any other martial art are not external assessments of progress, but rather the benefits of your training to yourself.

Basic Aikido Vocabulary

Agatsu – “Self victory.” According to the founder, true victory (masakatsu) is the victory one achieves over oneself (agatsu). Thus one of the founder’s “slogans” was masakatsu agatsu – “The true victory of self-mastery.”

Aikido – The word “Aikido” is made up of

three Japanese characters: ai = harmony, ki = spirit, mind, or universal

energy, do = the Way. Thus Aikido is “the Way of Harmony with Universal

Energy.”

However, aiki may also be interpreted as “accommodation to circumstances.”

This latter interpretation is somewhat nonstandard, but it avoids certain

undesirable metaphysical commitments and also epitomizes quite well both the

physical and psychological facets of Aikido.

Aikidoka – A practitioner of Aikido.

Aikikai – “Aiki association.” A term used to designate the organization created by the founder for the dissemination of Aikido.

Ai hanmi – Mutual stance where uke and nage each have the same foot forward (right-right, left-left).

Ai nuke – “Mutual escape.” An outcome of a duel where each participant escapes harm. This corresponds to the ideal of Aikido according to which a conflict is resolved without injury to any party involved.

Ai uchi – “Mutual kill.” An outcome of a duel where each participant kills the other. In classical Japanese swordsmanship, practitioners were often encouraged to enter a duel with the goal of achieving at least an ai uchi. The resolution to win the duel even at the cost of one’s own life was thought to aid in cultivating an attitude of single-minded focus on the task of cutting down one’s opponent. This single-minded focus is exemplified in Aikido in the technique, ikkyo, where one enters into an attacker’s range in order to affect the technique.

Ashi sabaki – Footwork. Proper footwork is essential in Aikido for developing strong balance and for facilitating ease of movement.

Atemi – (lit. Striking the Body.) Strike directed at the attacker for purposes of unbalancing or distraction. Atemi is often vital for bypassing or “short-circuiting” an attacker’s natural responses to Aikido techniques. The first thing most people will do when they feel their body being manipulated in an unfamiliar way is to retract their limbs and drop their center of mass down and away from the person performing the technique. By judicious application of atemi, it is possible to create a “window of opportunity” in the attacker’s natural defenses, facilitating the application of an Aikido technique.

Bokken = bokuto – Wooden sword. Many Aikido movements are derived from traditional Japanese fencing. In advanced practice, weapons such as the bokken are used in learning subtleties of certain movements, the relationships obtaining between armed and unarmed techniques, defenses against weapons, and the like.

Budo – “Martial way.” The Japanese character for “bu” (martial) is derived from characters meaning “stop” and (a weapon like a) “halberd.” In conjunction, then, “bu” may have the connotation “to stop the halberd.” In Aikido, there is an assumption that the best way to prevent violent conflict is to emphasize the cultivation of individual character. The way (do) of aiki is thus equivalent to the way of bu, taken in this sense of preventing or avoiding violence so far as possible.

Chiburi – “Shake off blood.” A sword movement where the sword is quickly drawn to one side at the end of a strike. Thus chiburi migi = shake off blood to the right.

Chokusen – Direct. Thus chokusen no irimi = direct entry.

Chudan – “Middle position.” Thus chudan no kamae = a stance characterized by having one’s hands or sword in a central position with respect to one’s body.

Chushin – Center. Especially, the center of one’s movement or balance.

Dan – Black belt rank. In IAF Aikido, the highest rank it is now possible to obtain is 9th dan. There are some Aikidoka who hold ranks of 10th dan. These ranks were awarded by the founder prior to his death, and cannot be rescinded. White belt ranks are called kyu ranks.

Do – Way/path. The Japanese character for “do” is the same as the Chinese character for Tao (as in “Taoism”). In aiki-do, the connotation is that of a way of attaining enlightenment or a way of improving one’s character through aiki.

Dojo – Literally “place of the Way.” Also “place of enlightenment.” The place where we practice Aikido. Traditional etiquette prescribes bowing in the direction of the shrine (kamiza) or the designated front of the dojo (shomen) whenever entering or leaving the dojo.

Dojo cho – The head of the dojo. A title. Currently, Moriteru Ueshiba (grandson of the founder) is dojo cho at World Aikido Headquarters (hombu dojo) in Tokyo, Japan.

Domo arigato gozaimas’ta – Japanese for “thank you very much” (for something that has already taken place). At the end of each class, it is proper to bow and thank the instructor and those with whom you’ve trained.

Domo arigato gozaimasu – Japanese for “thank you very much” (for something that is currently taking place).

Doshu – Head of the way (currently Moriteru Ueshiba, grandson of Aikido’s founder, Morihei Ueshiba). The highest official authority in IAF Aikido.

Douitashimashite – Japanese for “you are welcome.”

Engi – Interdependent origination (Sanskrit = pratityasamutpada). In Buddhist philosophy, phenomena have no unchanging essences. Rather, they originate and exist only in virtue of material and causal conditions. Without these material and causal conditions, there would be no phenomena. Furthermore, since the material and causal conditions upon which all phenomena depend are continually in flux, phenomena themselves are one and all impermanent. Since whatever is impermanent and dependent for existence on conditions has no absolute status (or is not absolutely real), it follows that phenomena (what are ordinarily called “things”) are have no absolute or independent existential status, i.e., they are empty. To cultivate a cognitive state in which the empty status of things is manifest is to realize or attain enlightenment. The realization of enlightenment, in turn, confers a degree of cognitive freedom and spontaneity that, among other (and arguably more important) benefits, facilitates the performance of martial techniques in response to rapidly changing circumstances. (See ku.)

Fudo shin – “Immovable mind.” A state of mental equanimity or imperturbability. The mind, in this state, is calm and undistracted (metaphorically, therefore, “immovable”). Fudomyo is a Buddhist guardian deity who carries a sword in one hand (to destroy enemies of the Buddhist doctrine), and a rope in the other (to rescue sentient beings from the pit of delusion, or from Buddhist hell-states). He therefore embodies the two-fold Buddhist ideal of wisdom (the sword) and compassion (the rope). To cultivate fudo shin is thus to cultivate a mind which can accommodate itself to changing circumstances without compromise of principles.

Fukushidoin – A formal title whose connotation is something approximating “assistant instructor.”

Furi kaburi – Sword-raising movement. This movement in found especially in ikkyo, irimi-nage, and shiho-nage.

Gedan – Lower position. Gedan no kamae is thus a stance with the hands or a weapon held in a lower position.

Gi (dogi) (keiko gi) – Training costume. Either judo-style or karate-style gi is acceptable in most dojo, but they should be white and cotton. (No black satin gi with embroidered dragons, please.)

Gomen nasai – Japanese for “Excuse me, I am sorry.”

Gyaku hanmi – Opposing stance (if uke has the right foot forward, nage has the left foot forward, if uke has the left foot forward, nage has the right foot forward).

Hakama

– Divided skirt usually worn by black-belt ranks in Aikido and Kendo. In

some dojo, the hakama is also worn by women of all ranks, and in some dojo by

all practitioners. The hakama has seven pleats. “The seven pleats symbolize

the seven virtues of budo,” O-Sensei said. “These are jin (benevolence),

gi (honor or justice), rei (courtesy and etiquette), chi (wisdom and

intelligence), shin (sincerity), chu (loyalty), and koh (piety). We find these

qualities in the distinguished samurai of the past. The hakama prompts us to

reflect on the nature of true bushido. Wearing it symbolizes traditions that

have been passed down to us from generation to generation. Aikido is born of

the bushido spirit of Japan, and in our practice we must strive to polish the

seven traditional virtues.”

Hakama

– Divided skirt usually worn by black-belt ranks in Aikido and Kendo. In

some dojo, the hakama is also worn by women of all ranks, and in some dojo by

all practitioners. The hakama has seven pleats. “The seven pleats symbolize

the seven virtues of budo,” O-Sensei said. “These are jin (benevolence),

gi (honor or justice), rei (courtesy and etiquette), chi (wisdom and

intelligence), shin (sincerity), chu (loyalty), and koh (piety). We find these

qualities in the distinguished samurai of the past. The hakama prompts us to

reflect on the nature of true bushido. Wearing it symbolizes traditions that

have been passed down to us from generation to generation. Aikido is born of

the bushido spirit of Japan, and in our practice we must strive to polish the

seven traditional virtues.”

Hanmi

– Triangular stance. Most often Aikido techniques are practiced with uke and

nage in pre-determined stances. This is to facilitate learning the techniques

and certain principles of positioning with respect to an attack. At higher

levels, specific hanmi cease to be of importance.

Hanmi

– Triangular stance. Most often Aikido techniques are practiced with uke and

nage in pre-determined stances. This is to facilitate learning the techniques

and certain principles of positioning with respect to an attack. At higher

levels, specific hanmi cease to be of importance.

Hanmi handachi – Position with nage sitting, uke standing. Training in hanmi handachi waza is a good way of practicing techniques as though with a significantly larger/taller opponent. This type of training also emphasizes movement from one’s center of mass (hara).

Happo – 8 directions, as in happo-undo (8 direction exercise) or happo-giri (8 direction cutting with the sword). The connotation here is really movement in all directions. In Aikido, one must be prepared to turn in any direction in an instant.

Hara – One’s center of mass, located about 2” below the navel. Traditionally this was thought to be the location of the spirit/mind/source of ki. Aikido techniques should be executed as much as possible from or through one’s hara.

Hasso no kamae – “Figure-eight” stance. The figure eight does not correspond to the Arabic numeral “8,” but rather to the Chinese/Japanese character which looks more like the roof of a house. In hasso no kamae, the sword is held up beside one’s head, so that the elbows spread down and out from the sword in a pattern resembling this figure-eight character.

Heijoshin – “Abiding peace of mind.” Cognitive equanimity. One goal of training in Aikido is the cultivation of a mind that is able to meet various types of adversity without becoming perturbed. A mind that is not easily flustered is a mind that will facilitate effective response to physical or psychological threats.

Henka waza – Varied technique. Especially beginning one technique and changing to another in mid-execution. Ex. beginning ikkyo but changing to irimi-nage.

Hombu Dojo – A term used to refer to the central dojo of an organization. Thus this usually designates Aikido World Headquarters. (See Aikikai.)

Hidari – Left.

Irimi – (lit. “Entering the Body.”) Entering movement. Many Aikidoka think that the irimi movement expresses the very essence of Aikido. The idea behind irimi is to place oneself in relation to an attacker in such a way that the attacker is unable to continue to attack effectively, and in such a way that one is able to control effectively the attacker’s balance. (See shikaku.)

Jinja – A (Shinto) shrine. There is an aiki jinja located in Iwama, Ibaraki prefecture, Japan.

Jiyu waza – Free-style practice of techniques. This usually involves more than one attacker who may attack nage in any way desired.

Jo – Wooden staff about 4’-5’ in length. The jo originated as a walking stick. It is unclear how it became incorporated into Aikido. Many jo movements come from traditional Japanese spear fighting, others may have come from jojutsu, but many seem to have been innovated by the founder. The jo is usually used in advanced practice.

Jodan – Upper position. Jodan no kamae is thus a stance with the hands or a weapon held in a high position.

Kachihayabi – “Victory at the speed of sunlight.” According to the founder, when one has achieved total self-mastery (agatsu) and perfect accord with the fundamental principles governing the universe (especially principles covering ethical interaction), one will have the power of the entire universe at one’s disposal, there no longer being any real difference between oneself and the universe. At this stage of spiritual advancement, victory is instantaneous. The very intention of an attacker to perpetrate an act of violence breaks harmony with the fundamental principles of the universe, and no one can compete successfully against such principles. Also, the expression of the fundamental principles of the universe in human life is love (ai), and love, according to the founder, has no enemies. Having no enemies, one has no need to fight, and thus always emerges victorious. (See agatsu and masakatsu.)

Kaeshi waza – Technique reversal (uke becomes nage and vice-versa). This is usually a very advanced form of practice. Kaeshi waza practice helps to instill a sensitivity to shifts in resistance or direction in the movements of one’s partner. Training so as to anticipate and prevent the application of kaeshi waza against one’s own techniques greatly sharpens Aikido skills.

Kaiso – The founder of Aikido (i.e., Morihei Ueshiba).

Kamae – A posture or stance either with or without a weapon. Kamae may also connote proper distance (ma ai) with respect to one’s partner. Although “kamae” generally refers to a physical stance, there is an important parallel in Aikido between one’s physical and one’s psychological bearing. Adopting a strong physical stance helps to promote the correlative adoption of a strong psychological attitude. It is important to try so far as possible to maintain a positive and strong mental bearing in Aikido.

Kami – A divinity, living force, or spirit. According to Shinto, the natural world is full of kami, which are often sensitive or responsive to the actions of human beings.

Kamiza – A small shrine, frequently located at the front of a dojo, and often housing a picture of the founder, or some calligraphy. One generally bows in the direction of the kamiza when entering or leaving the dojo, or the mat.

Kansetsu waza – Joint manipulation techniques.

Kata – A “form” or prescribed pattern of movement, especially with the jo in Aikido. (But also “shoulder.”)

Katame waza – “Hold-down” (pinning) techniques.

Katana – What is vulgarly called a “samurai sword.”

Katsu jin ken – “The sword that saves life.” Practitioners became increasingly interested in incorporating ethical principles into their discipline as Japanese swordsmanship became more and more influenced by Buddhism (especially Zen Buddhism) and Taoism. The consummate master of swordsmanship, according to some such practitioners, should be able not only to use the sword to kill, but also to save life. The concept of katsu jin ken found some explicit application in the development of techniques which would use non-cutting parts of the sword to strike or control one’s opponent, rather than to kill him/her. The influence of some of these techniques can sometimes be seen in Aikido. Other techniques were developed by which an unarmed person (or a person unwilling to draw a weapon) could disarm an attacker. These techniques are frequently practiced in Aikido. (See setsu nin to.)

Keiko – Training. The only secret to success in Aikido.

Ken – Sword.

Kensho – Enlightenment. (See mokuso and satori.)

Ki – Mind. Spirit. Energy. Vital force. Intention. (Chinese = Chi) For many Aikidoka, the primary goal of training in Aikido is to learn how to “extend” ki, or to learn how to control or redirect the ki of others. There are both “realist” and anti-realist interpretations of ki. The ki-realist takes ki to be, literally, a kind of energy, or life force, which flows within the body. Developing or increasing one’s own ki, according to the ki-realist, thus confers upon the Aikidoka greater power and control over his/her own body, and may also have the added benefits of improved health and longevity. According to the ki-anti-realist, ki is a concept which covers a wide range of psycho-physical phenomena, but which does not denote any objectively existing energy. The ki-anti-realist believes, for example, that to “extend ki” is just to adopt a certain kind of positive psychological disposition and to correlate that psychological disposition with just the right combination of balance, relaxation, and judicious application of physical force. Since the description “extend ki” is somewhat more manageable, the concept of ki has a class of well-defined uses for the ki-anti-realist, but does not carry with it any ontological commitments beyond the scope of mainstream scientific theories.

Kiai – A shout delivered for the purpose of focusing all of one’s energy into a single movement. Even when audible kiai are absent, one should try to preserve the feeling of kiai at certain crucial points within Aikido techniques.

Kihon – (Something which is) fundamental. There are often many seemingly very different ways of performing the same technique in Aikido. To see beneath the surface features of the technique and grasp the core common is to comprehend the kihon.

Ki musubi – ki no musubi – Literally “knotting/tying-up ki.” The act/-100process of matching one’s partner’s movement/intention at its inception, and maintaining a connection to one’s partner throughout the application of an Aikido technique. Proper ki musubi requires a mind that is clear, flexible, and attentive. (See setsuzoku.)

Kohai – A student junior to oneself.

Kokoro – “Heart” or “mind.” Japanese folk psychology does not distinguish clearly between the seat of intellect and the seat of emotion, as does Western folk psychology.

Kokyu – Breath. Part of Aikido is the development of “kokyu ryoku,” or “breath power.” This is the coordination of breath with movement. A prosaic example: When lifting a heavy object, it is generally easier when breathing out. Also breath control may facilitate greater concentration and the elimination of stress. In many traditional forms of meditation, focus on the breath is used as a method for developing heightened concentration or mental equanimity. This is also the case in Aikido. A number of exercises in Aikido are called “kokyu ho,” or “breath exercises.” These exercises are meant to help one develop kokyu ryoku.

Kotodama – A practice of intoning various sounds (phonetic components of the Japanese language) for the purpose of producing mystical states. The founder of Aikido was greatly interested in Shinto and neo-Shinto mystical practices, and he incorporated a number of them into his personal Aikido practice.

Ku – Emptiness. According to Buddhism, the fundamental character of things is absence (or emptiness) of individual unchanging essences. The realization of the essenceless-ness of things is what permits the cultivation of psychological non-attachment, and thus cognitive equanimity. The direct realization of (or experience of insight into) emptiness is enlightenment. This shows up in Aikido in the ideal of developing a state of cognitive openness, permitting one to respond immediately and intuitively to changing circumstances. (See mokuso.)

Kumijo – jo matching exercise or partner practice.

Kumitachi – Sword matching exercise or partner practice.

Kuzushi – The principle of destroying one’s partner’s balance. In Aikido, a technique cannot be properly applied unless one first unbalances one’s partner. To achieve proper kuzushi, in Aikido, one should rely primarily on position and timing, rather than merely on physical force.

Kyu – White belt rank. (Or any rank below shodan.)

Ma ai – Proper distancing or timing with respect to one’s partner. Since Aikido techniques always vary according to circumstances, it is important to understand how differences in initial position affect the timing and application of techniques.

Mae – Front. Thus mae ukemi = “forward fall/roll.”

Masakatsu – “True victory.” (See agatsu and kachihayabi.)

Michibiki – An aspect of Aikido movement that involves leading, rather than pushing or pulling, one’s partner. As with many other concepts in Aikido, there are both physical and cognitive dimensions to michibiki. Physically, one may lead one’s partner through subtle guiding or redirection of the attacking motion. Psychologically, one may lead one’s partner through “baiting” (presenting apparent opportunities for attack). Frequently both physical and cognitive elements are employed in concert. For example, if uke reaches for nage’s wrist, nage may move the wrist just slightly ahead of uke’s grasp, at such a pace that uke is fooled into thinking s/he will be able to seize it, thus continuing the attempt to grab and following the lead where nage wishes.

Migi – Right.

Misogi – Ritual purification. Aikido training may be looked upon as a means of purifying oneself; eliminating defiling characteristics from one’s mind or personality. Although there are some specific exercises for misogi practice, such as breathing exercises, in point of fact, every aspect of Aikido training may be looked upon as misogi. This, however, is a matter of one’s attitude or approach to training, rather than an objective feature of the training itself.

Mokuso – Meditation. Practice often begins or ends with a brief period of meditation. The purpose of meditation is to clear one’s mind and to develop cognitive equanimity. Perhaps more importantly, meditation is an opportunity to become aware of conditioned patterns of thought and behavior so that such patterns can be modified, eliminated or more efficiently put to use. In addition, meditation may occasion experiences of insight into various aspects of Aikido (or, if one accepts certain Buddhist claims, into the very structure of reality). Ideally, the sort of cognitive awareness and focus that one cultivates in meditation should carry over into the rest of one’s practice, so that the distinction between the “meditative mind” and the “normal mind” collapses.

Mudansha – Students without black-belt ranking.

Mushin – Literally “no mind.” A state of cognitive awareness characterized by the absence of discursive thought. A state of mind in which the mind acts/reacts without hypostatization of concepts. Mushin is often erroneously taken to be a state of mere spontaneity. Although spontaneity is a feature of mushin, it is not straightforwardly identical with it. It might be said that when in a state of mushin, one is free to use concepts and distinctions without being used by them.

Musubi – “Tying up” or “uniting”. One of the strategic objectives in applying Aikido techniques in to merge with (= musubi) and redirect the aggressive impulse (= ki) of an attacker in order to gain control of it. Thus “ki musubi” or “ki no musubi” is one of the goals of Aikido. There is a cognitive as well as a physical dimension to musubi. Ideally, at the most advanced levels of Aikido, one learns to detect signs of aggression in a potential attacker before a physical assault has been initiated. If one learns to identify aggressive intent and defuse or redirect it before the attack is launched, one may achieve victory without physical confrontation. Also, by developing heightened sensitivity to the cues that may precede a physical attack, one thereby gains a strategic advantage, making possible pre-emptive action or, perhaps, escape. This heightened sensitivity to aggressive cues is only possible as a result of training one’s awareness as well as one’s technical abilities.

Nagare – Flowing. One goal of Aikido practice is to learn not to oppose physical force with physical force. Rather, one strives to flow along with physical force, redirecting it to one’s advantage.

Nage – The thrower.

Obi – A belt.

Omote – “The front,” thus, a class of movements in Aikido in which nage enters in front of uke.

Omoto Kyo – One of the so-called “new-religions” of Japan. Omoto Kyo is a syncretic amalgam of Shintoism, neo-Shinto mysticism, Christianity, and Japanese folk religion. The founder of Aikido was a devotee of Omoto Kyo and incorporated some elements from it into his Aikido practice. The founder insisted, however, that one need not be a devotee of Omoto Kyo in order to study Aikido or to comprehend the purpose or philosophy of Aikido.

Onegai shimasu – “I welcome you to train with me,” or literally, “I make a request.” This is said to one’s partner when initiating practice.

Osaewaza – Pinning techniques.

O-Sensei – Literally, “Great Teacher,” i.e., Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido.

Randori – Free-style “all-out” training. Sometimes used as a synonym for jiyu waza. Although Aikido techniques are usually practiced with a single partner, it is important to keep in mind the possibility that one may be attacked by multiple aggressors. Many of the body movements of Aikido (tai sabaki) are meant to facilitate defense against multiple attackers.

Reigi – Etiquette. Observance of proper etiquette at all times (but especially observance of proper dojo etiquette) is as much a part of one’s training as the practice of techniques. Observation of reigi indicates one’s sincerity, one’s willingness to learn, and one’s recognition of the rights and interests of others.

Satori – Enlightenment. In Buddhism, enlightenment is characterized by a direct realization or apprehension of the absence of unchanging essences behind phenomena. Rather, phenomena are seen to be empty of such essences – phenomena exist in thoroughgoing interdependence (engi). As characterized by the founder of Aikido, enlightenment consists in realizing a fundamental unity between oneself and the (principles governing) the universe. The most important ethical principle the Aikidoist should gain insight into is that one should cultivate a spirit of loving protection for all things. (See ku and shinnyo.)

Sensei – Teacher. It is usually considered proper to address the instructor during practice as “Sensei” rather than by his/her name. If the instructor is a permanent instructor for one’s dojo or for an organization, it is proper to address him/her as “Sensei” off the mat as well.

Seiza – Sitting on one’s knees. Sitting this way requires acclimatization, but provides both a stable base and greater ease of movement than sitting cross-legged.

Sempai – A student senior to oneself.

Setsu nin to – “The sword that kills.” Although this would seem to indicate a purely negative concept, there is, in fact, a positive connotation to this term. Apart from the common assumption that killing may sometimes be a “necessary evil” which may serve to prevent an even greater evil, the concept of killing has a wide variety of metaphorical applications. One may, for example, strive to “kill” such harmful character traits as ignorance, selfishness, or (excessive) competitiveness. Some misogi sword exercises in Aikido, for example, involve imagining that each cut of the sword destroys some negative aspect of one’s personality. In this way, setsu nin to and katsu jin ken (the sword that saves) coalesce.

Setsuzoku – Connection. Aikido techniques are generally rendered more efficient by preserving a connection between one’s center of mass (hara) and the outer limits of the movement, or between one’s own center of mass and that of one’s partner. Also, setsuzoku may connote fluidity and continuity in technique. On a psychological level, setsuzoku may connote the relationship of action-response that exists between oneself and one’s partner, such that successful performance of Aikido techniques depends crucially upon timing one’s own actions and responses to accord with those of one’s partner. Physically, setsuzoku correlates with leverage and with the most efficient application of force to the task of controlling one’s partner’s balance and mobility.

Shidoin – A formal title meaning, approximately, “instructor.”

Shihan – A formal title meaning, approximately, “master instructor.” A “teacher of teachers.”

Shikaku – Literally “dead angle.” A position relative to one’s partner where it is difficult for him/her to (continue to) attack, and from which it is relatively easy to control one’s partner’s balance and movement. The first phase of an Aikido technique is often to establish shikaku.

Shikko – Samurai walking (“knee walking”). Shikko is very important for developing a strong awareness of one’s center of mass (hara). It also develops strength in one’s hips and legs.

Shinkenshobu – Lit. “Duel with live swords.” This expresses the attitude one should have about Aikido training, i.e., one should treat the practice session as though it were, in some respects, a life-or-death duel with live swords. In particular, one’s attention during Aikido training should be single-mindedly focused on Aikido, just as, during a life-or-death duel, one’s attention is entirely focused on the duel.

Shinnyo – “Thusness” or “suchness.” A term commonly used in Buddhist philosophy (and especially in Zen Buddhism) to denote the character of things, as they are experienced without filtering the experiences through an overt conceptual framework. There is some question whether “pure” uninterpreted experience (independent of all conceptualization/categorization) is possible given the neurological/cognitive makeup of human beings. However, shinnyo can also be taken to signify experience of things as empty of individual essences (see “ku”).

Shinto – “The way of the gods.” The indigenous religion of Japan. The founder of Aikido was deeply influenced by Omoto Kyo, a religion largely grounded in Shinto mysticism. (See kami.)

Shodan – First degree black belt. (Nidan = second degree black belt, followed by sandan, yondan, godan, rokudan, nanadan, hachidan, kyudan, judan.)

Shomen – Front or top of head. Also the designated front of a dojo.

Shoshin – Beginner’s mind. Progress in Aikido training requires that one approach one’s training with a mind that is free from unfounded bias. Although we can say in one respect that we frequently practice the same techniques over and over again, often against the same attack, there is another sense in which no attack is ever the same, and no application of technique is ever the same. There are subtle variations in the circumstances of every interaction between attacker and defender. These small differences may sometimes translate into larger differences. To assume that one already knows a technique constitutes a “locking in” of the mind to a pre-set dispositional pattern of response, resulting in a corresponding loss of adaptability. Prejudgment also may deprive one of the opportunity to learn new principles of movement. For example, it is common for people upon seeing a different way of performing a technique to judge it to be wrong. This judgment is frequently based on a superficial observation of the technique, rather than an appreciation of the underlying principles upon which the technique is based.

Shugyo – Discipline. Traveling in pursuit of Truth. To pursue Aikido, or any martial art, as a path to self-improvement involves more than training. The word “shugyo” connotes a continual striving for technical and personal excellence. Keiko, or training, is only one component of such striving. To pursue Aikido as a Way requires a continual reexamination and correction of oneself, one’s attitudes, reactions, dispositions to like or dislike, etc.

Soto – “Outside.” Thus, a class of Aikido movements executed, especially, outside the attacker’s arm(s). (See uchi.)

Suburi – Repetitive practice in striking and thrusting with jo or bokken. Such repetitive practice trains not only one’s facility with the weapon, but also general fluidity of body movement that is applicable to empty-hand training.

Sukashi waza – Techniques performed without allowing the attacker to complete a grab or to initiate a strike. Ideally, one should be sensitive enough to the posture and movements of an attacker (or would-be attacker) that the attack is neutralized before it is fully executed. A great deal of both physical and cognitive training is required in order to attain this ideal.

Suki – An opening or gap where one is vulnerable to attack or application of a technique, or where one’s technique is otherwise flawed. Suki may be either physical or psychological. One goal of training is to be sensitive to suki within one’s own movement or position, as well as to detect suki in the movement or position of one’s partner. Ideally, a master of Aikido will have developed his/her skill to such an extent that he/she no longer has any true suki.

Sutemi – Literally “to throw-away the body.” The attitude of abandoning oneself to the execution of a technique (in judo, a class of techniques where one sacrifices one’s own balance/position in order to throw one’s partner). (See aiuchi.) In Aikido, sutemi may connote an attitude of fearlessness by which one enters into an attacker’s space with no thought of preserving one’s own safety. Far from being simple recklessness, however, sutemi is based upon an absolute commitment to a strategy for neutralizing the attack. Techniques in Aikido cannot be applied tentatively if they are to be effective. Rather, one must respond instantly to a threat and take decisive action. Thus, in a manner of speaking, sutemi requires not only throwing away the body, but throwing away the self as well.

Suwari waza – Techniques executed with both uke and nage in a seated position. These techniques have their historical origin (in part) in the practice of requiring all samurai to sit and move about on their knees while in the presence of a daimyo (feudal lord). In theory, this made it more difficult for anyone to attack the daimyo. But this was also a position in which one received guests (not all of whom were always trustworthy). In contemporary Aikido, suwari waza is important for learning to use one’s hips and legs.

Tachi – A type of Japanese sword (thus tachi-tori = sword-taking). (Also “standing position.”)

Tachi waza – Standing techniques.

Taijutsu – “Body arts,” i.e., unarmed practice.

Tai no henko – tai no tenkan – Basic blending practice involving turning 180 degrees.

Tai sabaki – Body movement.

Takemusu aiki – A “slogan” of the founder’s meaning “infinitely generative martial art of aiki.” Thus, a synonym for Aikido. The scope of Aikido is not limited only to the standard, named techniques one studies regularly in practice. Rather, these standard techniques serve as repositories of more fundamental principles (kihon). Once one has internalized the kihon, it is possible to generate a virtually infinite variety of new Aikido techniques in accordance with novel conditions.

Taninsugake – Training against multiple attackers, usually from grabbing attacks.

Tanto – A dagger.

Tegatana – “Hand sword,” i.e. the edge of the hand. Many Aikido movements emphasize extension “through” one’s tegatana. Also, there are important similarities obtaining between Aikido sword techniques, and the principles of tegatana application.

Tenkan – Turning movement, esp. turning the body 180 degrees. (See tai no tenkan.)

Tenshin – A movement where nage retreats 45 degrees away from the attack (esp. to uke’s open side).

Tsuki – A punch or thrust (esp. an attack to the midsection).

Uchi – “Inside.” A class of techniques where nage moves, especially, inside (under) the attacker’s arm(s). (But also a strike, e.g., shomen uchi.)

Uchi deshi – A live-in student. A student who lives in a dojo and devotes him/herself both to training and to the maintenance of the dojo (and sometimes to personal service to the sensei of the dojo).

Ueshiba Kisshomaru – The son of the founder of Aikido and second Aikido doshu.

Ueshiba Morihei – The founder of Aikido. (See O-Sensei and kaiso.)

Ueshiba Moriteru – The grandson of the founder and current Aikido doshu.

Uke – Person being thrown (receiving the technique). At high levels of practice, the distinction between uke and nage becomes blurred. In part, this is because it becomes unclear who initiates the technique, and also because, from a certain perspective, uke and nage are thoroughly interdependent.

Ukemi – Literally “receiving [with/through] the body,” thus, the art of falling in response to a technique. Mae ukemi are front roll-falls, ushiro ukemi are back roll-falls. Ideally, one should be able to execute ukemi from any position and in any direction. The development of proper ukemi skills is just as important as the development of throwing skills and is no less deserving of attention and effort. In the course of practicing ukemi, one has the opportunity to monitor the way one is being moved so as to gain a clearer understanding of the principles of Aikido techniques. Just as standard Aikido techniques provide strategies for defending against physical attacks, so does ukemi practice provide strategies for defending against falling (or even against the application of an Aikido or Aikido-like technique).

Ura – “Rear.” A class of Aikido techniques executed by moving behind the attacker and turning. Sometimes ura techniques are called tenkan (turning) techniques.

Ushiro – Backwards or behind, as in ushiro ukemi or falling backwards.

Waza – Techniques. Although in Aikido we have to practice specific techniques, Aikido as it might manifest itself in self-defense may not resemble any particular, standard Aikido technique. This is because Aikido techniques encode strategies and types of movement that are modified in accordance with changing conditions. (See kihon.)

-tori (-dori) – Taking away , e.g. tanto-tori (knife-taking).

Yoko – Side.

Yokomen – Side of the head.

Yudansha – Black belt holder (any rank).

Zanshin – Lit. “remaining mind/heart.” Even after an Aikido technique has been completed, one should remain in a balanced and aware state. Zanshin thus connotes “following through” in a technique, as well as preservation of one’s awareness so that one is prepared to respond to additional attacks. Zanshin has both a physical and a cognitive dimension. The physical dimension is represented by maintaining correct posture and balance even when a technique has been completed. The cognitive dimension consists partly in preserving the same overall mindset at all phases of technique application – there is nothing any more special about having completed a technique than there is about beginning or continuing it. Also, upon completing a technique, one’s state of cognitive readiness is not abandoned: one remains ready either for a renewed attack by the same opponent, or for an attack from another direction by a new attacker.

Zen – A school or division of Buddhism characterized by techniques designed to produce enlightenment. In particular, Zen emphasizes various sorts of meditative practices, which are supposed to lead the practitioner to a direct insight into the fundamental character of reality (see ku and mokuso). Practitioners of many martial arts, including Aikido, believe that adopting a mindful attitude towards martial arts training can promote some of the same insights as more traditional meditative practices.

Zori – Sandals worn when off the mat to help keep the mat clean!

Common Attacks

Katate

tori (also katate mochi) – One hand holding one hand.

Katate

tori (also katate mochi) – One hand holding one hand.

Kosa dori (also naname mochi) – One hand holding one hand, cross-body.

Morote tori – Two hands holding one hand.

Kata tori – Shoulder hold.

Ryokata tori – Grabbing both shoulders.

Ryote tori – Two hands holding two hands.

Mune dori – One or two hand lapel hold.

Hiji tori – Elbow grab.

Ushiro tekubi tori (ushiro ryote tori / ushiro ryokatate tori) – Wrist grab from the back.

Ushiro ryokata tori – As above from the back.

Ushiro kubi shime – Rear choke.

Shomen uchi – Overhead strike to the head.

Yokomen uchi – Diagonal strike to the side of the head.

Tsuki – Straight thrust (punch), esp. to the midsection.

Basic Techniques

Ikkyo (ikkajo / ude osae) – omote and ura (irimi and tenkan); arm pin

Nikyo (nikajo / kote mawashi) – omote and ura (irimi and tenkan); wrist turn

Sankyo (sankajo / kote hineri) – omote and ura (irimi and tenkan); wrist twist

Yonkyo (yonkajo / tekubi osae) – omote and ura (irimi and tenkan); wrist pin

Gokyo (ude nobashi) – omote and ura (irimi and tenkan); arm stretching

Throws

Irimi

nage (also kokyu nage) – Entering throw (“20 year”

technique).

Irimi

nage (also kokyu nage) – Entering throw (“20 year”

technique).

Juji nage (juji garami) – Arm entwining throw.

Kaiten nage – Rotary throw. Uchi and soto, omote and ura (irimi and tenkan).

Kokyu nage – Breath throws.

Koshi nage – Hip throw.

Kote gaeshi – Wrist turn-out.

Shiho nage – “Four direction” throw.

Sumiotoshi – “Corner drop.” Omote and ura (irimi and tenkan).

Tenchi nage – “Heaven and earth” throw. Omote and ura (irimi and tenkan).

Pronunciation

A – aardvark

I – pizza

U – blue

E – egg

O – bone

Counting

In order to count up to 99, all you need to know is the Japanese terms for 1 through 10.

one = ichi

two = ni

three = san

four = yon (or shi)

five = go

six = roku

seven = nana (or shichi)

eight = hachi

nine = kyu

ten = jyu

Above ten, we would say something to the effect of “10 and 2” to stand for “12.” Therefore,

11 = “ten (and) one” = “jyu ichi”

12 = “ten (and) two” = “jyu ni”

13 = “ten (and) three” = “jyu san”

14 = “ten (and) four” = “jyu shi” or “jyu yon”

15 = “ten (and) five” = “jyu go”

16 = “ten (and) six” = “jyu roku”

17 = “ten (and) seven” = “jyu nana” or “jyu shichi”

18 = “ten (and) eight” = “jyu hachi”

19 = “ten (and) nine” = “jyu kyu”

For numbers from 20 through 99, you would say something like “3 tens and 6” to mean “36.”

36 = “3 tens and 6” = “san jyu roku”

43 = “4 tens and 3” = “yon jyu san”

71 = “7 tens and 1” = “nana jyu ichi”

99 = “9 tens and 9” = “kyu jyu kyu”

Counting higher is basically the same.

100 = “hyaku”

1000 = “sen”

10000 = “man”

So,

101 = “hundred (and) one” = “hyaku ichi”

201 = “two hundred (and) one” = “ni hyaku ichi”

546 = “five hundred (and) four tens (and) six” = “go hyaku yon jyu roku”

3427 = “san zen yon hyaku ni jyu nana (or shichi)” (note that “sen” becomes “zen” after a voiced consonant line “n”)

23456 = “ni man san zen yon hyaku go jyu roku”

Some anomalies:

Use “shi” for “four” only in the single digit column. So, you can use “shi” or “yon” in 3654, but use “yon” for 40, 400, 4000, etc.

Use “shichi” for “seven” only in the single digit column. So, you can use “shichi” or “nana” in 9607, but use “nana” for 70, 700, 7000, etc.

600 = “roppyaku” (not “roku hyaku”)

800 = “happyaku” (not “hachi hyaku”); 8000 = “hassen” (not “hachi sen”)

The Essence of Aikido

The following are some of O-Sensei Ueshiba’s teachings concerning the essence of Aikido:

Aikido is a manifestation of a way to reorder the world of humanity as though everyone were of one family. Its purpose is to build a paradise right here on earth.

Aikido is nothing but an expression of the spirit of Love for all living things.

It is important not to be concerned with thoughts of victory and defeat. Rather, you should let the ki of your thoughts and feelings blend with the Universal.