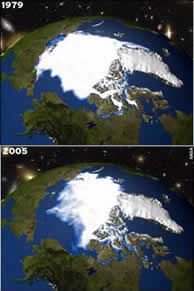

Record Arctic sea ice lossNASA researchers using Earth observation satellites are reporting a significant loss in Arctic sea ice this year. On 21 September sea ice extent dropped to 2.05 million square miles, the lowest extent yet recorded in the satellite record. Incorporating the 2005 minimum using satellite data going back to 1978, with a projection for ice growth in the last few days of this September, brings the estimated decline in Arctic sea ice to 8.5 percent per decade over the 27 year satellite record. NERC Chief Executive Professor Alan Thorpe said: ‘These results seem alarming and certainly highlight the need for permanent monitoring and increased knowledge of the Arctic system. State of the art climate models show that by the end of the century sea ice cover in the Arctic will have reduced to nil. Of course planet Earth is a very complex system. We know that as ice cover reduces, less heat from the sun is reflected back in to space. But the ice sheets act as an insulation blanket for the Arctic waters beneath, so reduced sea ice coverage will lead to more heat loss from the ocean to the atmosphere in winter. The colder water temperatures may promote ice growth.’ ‘But we cannot rely on nature to bring the temperature back down. It is highly likely that human activities are responsible for a major change to one of the planet’s most important regions - both in terms of biodiversity and in maintaining this planet within habitable boundaries. Substantially reducing the human input of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere would probably, in the long term, reverse these trends, so reports of global warming having reached the point of no return may be premature. But these issues must be addressed not just by scientists - by increasing knowledge and providing solutions - but by industry and policymakers adopting these solutions as a matter of urgency,’ he added. Professor Chris Rapley, director of NERC’s British Antarctic Survey said: ‘Climate models predict stronger warming in the polar regions and, lo and behold, there it is. We are seeing the Antarctica peninsula heating up dramatically with Alaska and parts of Siberia. These three spots are warming faster than anywhere else on the planet. It’s happening so rapidly that even if the causes are natural we need to monitor and understand them.’ Change in average annual

surface air temperature from 1960-1990 to 2070-2100 Satellites have made continual observations of Arctic sea ice extent since 1978, recording a general decline throughout that period. Since 2002, satellite records have revealed early onsets of springtime melting in the areas north of Alaska and Siberia. In addition, the 2004-2005 winter season showed a smaller recovery of sea ice extent than any previous winter in the satellite record and the earliest onset of melt throughout the Arctic. Next week the European Space Agency launch CryoSat, a satellite proposed by Duncan Wingham from NERC’s Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM), which has been specifically designed to address the uncertainty of climate change at the poles. CryoSat will measure sea ice loss in unprecedented detail. The satellite is set to provide the best information yet on the state of sea ice and the ice sheets at both poles. The three-year mission is scheduled to blast off from the Khrunichev Space Centre, Plesetsk, Russia, on 8 October. CPOM director, Professor Duncan Wingham, who proposed the mission, said: 'The great difficulty at present is to figure out whether changes in ice cover are due to melting or to changes in the winds that shift the ice around. The only way to do this is examine the entire Arctic at the same time. CryoSat is the first satellite designed to do this job, and after six years in the making, we are really looking forward to getting our hands on the data.’ But the satellite will do more than just measure Arctic sea ice: its orbit takes it over the major ice sheets – Antarctica and Greenland. Scientists will be able to use CryoSat data to accurately predict sea level rise caused by melting ice sheets. CryoSat’s altimeter, the primary instrument onboard, has the ability to measure ice sheets and sea ice with unprecedented accuracy. Until now satellites have been unable to monitor melting ice at the very point where it is most significant: at the ice edge. CryoSat’s ability to do just that thrills scientists working in the field, while the altimeter’s ability to pick out sea ice of around one kilometre in diameter will greatly improve annual melt estimations. (For more Cryosat information see www.esa.int) With the exception of May 2005, every month since December 2004 has seen the lowest monthly average since the satellite record began, but more data are needed to fully understand this pattern. Sea ice records prior to late 1978, for example, are comparatively sparse, but they do imply that the recent decline exceeds previous sea ice lows. Arctic sea ice typically reaches its minimum in September, at the end of the summer melt season. The last four Septembers (2002-2005) have seen sea ice extents 20 percent below the mean September sea ice extent for 1979-2000. Scientists are working to understand the extent to which these decreases in sea ice are due to naturally occurring climate variability or longer-term human influenced climate changes. Scientists believe that the Arctic Oscillation, a major atmospheric circulation pattern that can push sea ice out of the Arctic, may have contributed to the reduction of sea ice in the mid-1990s by making the sea ice more vulnerable to summertime melt. http://www.nerc.ac.uk/publications/latestpressrelease/2005-48arcticiceloss.asp |

|||||