By Jöran Reske

Compostable packaging sees a bright future ahead

Compostable plastic is a relatively new, environmentally friendly option for packaging material. Yet how popular and applicable is it proving to be? A German study and wider European experience provide some clues.

The world produces over 200 million tonnes of plastic each year. Most post-consumer plastic products are still not reused or recovered, but are dumped in landfills. In addition, any material recycling or energy recovery often compromise the environmental effects. One contribution to a more sustainable recovery of plastic waste might well be the use of compostable plastics. Products could then be recovered after use by composting or anaerobic fermentation – though the latter currently has some limitations due to process technology. Thus, a major proportion of the plastic waste stream could be re-integrated into the natural carbon cycle – with the special advantage of being carbon-neutral for those materials derived from renewable resources.

NEW CLASS OF PLASTICS

This new class of compostable plastics contains a variety of different materials. Many are made of renewable resources such as starch, cellulose and other polysaccharides, fibres, proteins and plant oils. The most prominent materials based on renewable resources in the marketplace are provided by:

- Novamont (Mater Bi®, starch)

- Plantic Technologies Ltd (PlanticTM,

starch)

- Rodenburg (Solanyl®, starch)

- Natureworks LLC (formerly Cargill Dow: Natureworks®

PLA, polylactic acid)

- Innovia Films (formerly UCB: Natureflex®,

cellulose)

- Procter & Gamble (Nodax® PHA, polyhydroxy alkanoates).

Ecoflex® from BASF represents a small group of compostable plastics from fossil resources (a type of co-polyester). In many cases, fossil resources are necessary to complement renewable resources in order to achieve the technical performance required for products such as packaging. Ecoflex and similar products are compostable just like those materials based on renewable resources – biodegradability is a result of a polymer’s chemical structure and is independent of the material’s origin.1

WHAT IS A COMPOSTABLE PLASTIC?

A product’s biodegradable nature can be utilized in waste management. If materials biodegrade at rates similar to those of, for example, vegetable waste, they are considered ‘compostable’. Like biowaste (the biodegradable fraction of waste) from households, such products can be treated in composting plants.

Vanishing act: a compostable cup biodegrades over 1,

15, 30 and 50 days.

PHOTO: NATUREWORKS

The most important application of such plastics in the short and medium term is in the packaging sector. EU institutions have acknowledged the biological recovery of compostable packaging as a means to fulfil the requirements of the European Directive on Packaging and Packaging Waste 94/62/EC and its amendment 2004/12/EC.2

The performance of compostable plastic products during biological waste treatment depends primarily on their rapid disintegration and complete biodegradation within a given time frame. This has been standardized by working groups on national and international standards.3 These standards follow the same rationale; in order to guarantee their safe recovery, materials have to be characterized with respect to the following four categories:

- chemical composition, including heavy metals and organic

pollutants

- inherent and ultimate biodegradability as established in

laboratory tests

- disintegration within a defined time frame

- ecotoxicity of the resulting compost.

All these requirements have to be fulfilled at the same time in order to

qualify a plastic material used in packaging as ‘compostable’.

As an example, the British and European Standard BS EN 13432 has been

developed4

to support and ensure the safe biological recovery of compostable packaging

and thus implement the regulation provided by Directives 94/62/EC and

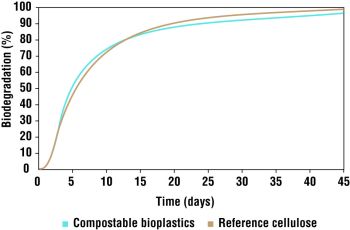

2004/12/EC. Figure 1 shows a typical degradation curve of a compostable

plastic tested according to EN 13432.

CERTIFICATION OF COMPOSTABILITY

To guarantee compliance with waste management requirements, the bioplastic and composting industries have jointly developed a certification scheme for products for which these new plastics are used, as packaging by retailers, for example. The scheme includes a logo to demonstrate a product’s certification.

Figure 1. Degradation curve of a compostable plastic tested in two separate sample runs according to EN 13432, compared with a reference cellulose material

The scheme provides an independent third-party certification of compostable plastic products and helps to fulfil producer responsibility beyond the self-declaration mechanism of the Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive. A voluntary Environmental Agreement has been signed by the most important producers (BASF, Cargill Dow [Natureworks], Novamont, Rodenburg) and officially acknowledged by the European Commission.5 The recovery of certified compostable plastics is likely to be eligible to fulfil the quota for the next amendment of the Packaging Waste Directive – the subject of recent discussions within the EU and Member States.

In addition, a technical framework has been provided by co-operation between EU certification institutions. This joint approach is so far supported by DIN CERTCO (Germany), the Composting Association (UK), the Keurmerk Instituut (the Netherlands) and the Polish Packaging Institute COBRO.

A co-operation network of certification institutions has also been established at a global level to facilitate trade and the application of certified products by mutual recognition of others’ certificates.6 A website (www.iccn.org) has been launched to provide information about the network.

Current members of the International Compostability Certification Network (ICCN) and co-operating institutions include:

- DIN CERTCO, Europe

- Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI), US

- Biodegradable Plastics Society (BPS), Japan

- Biodegradable Materials Group (BMG), China – agreement with BPS about

mutual recognition of test reports

- Environmentally Biodegradable Plastics Association (EBPA), Taiwan – Memorandum of Understanding about future co-operation.

The worldwide co-operation of certification systems and the mutual recognition of certificates among institutions will support both the application of certified materials and the establishment of biological recovery systems for plastic products qualified as compostable. The ICCN invites further countries to participate and negotiations are underway with institutions in several countries both at an EU and a global level.7

PRACTICALITY OF THE BIOLOGICAL RECOVERY OPTION

Biodegradable packaging in Europe is indicated by the orange ‘compostable’ symbol. Institutions worldwide have joined forces to issue certifications of compostibility to promote trade and the application of certified bioplastic products

Once a system for the testing, certification and labelling of compostable products have been established and the compostability of certified products have been acknowledged by operators of composting plants and others, there remains one basic question about the possible organic recovery of these products.

Is it feasible to collect such materials via the ‘biobin’, an extra bin

supplied to households for the separate collection of biowaste? In other

words, will consumers sort them separately into the biobin and not put in

traditional plastic packaging? Or will they be confused by the new option?

Most of the new products cannot be distinguished easily from conventional

plastics just by their look or touch.

A clear logo represents an important means of differentiation. To make

things work, it is necessary to communicate information about the logo and

the new approach to consumers, local authorities and composting plant

operators.8

THE KASSEL EXPERIENCE

The German Ministry of Consumer Protection, Food and Agriculture funded a study of this problem, which was carried out between 2001 and 2003 in the city of Kassel. Kassel is located in the middle of Germany and is home to 200,000 inhabitants of average social and financial background.

|

The scheme provides a third-party certification for compostable

plastics

|

A range of about a dozen different certified products were delivered along routine distribution channels to some 80 participating retailers and sold to consumers. Based on information that had been provided, consumers were expected to sort labelled packaging into the biobin after use and to avoid disposing of conventional plastic items in this bin.

Rosy prospect: consumers have shown support towards biopackaging

Households were provided with an information brochure together with a compostable bag for the collection of biowaste (a ‘biobag’).9 During the campaign, several press articles featured the project and some local TV stations reported its progress. A three-metre high display of product samples was showcased for several weeks in public places such as the town hall, university cafeteria and a central bank office.

Expensive methods of communication such as TV advertisements were avoided in order to obtain a realistic picture of the feasibility of informing consumers that could be cost-effectively extended to the whole of Germany. The communication cost of approximately E2.25 per inhabitant was considerable. However, given the duration of the project (21 months) and the potential savings from economies of scale, the Kassel approach seems suitable for implementation at a national level, according to the experts involved from the waste management service company, Interseroh GmbH.

Consumer reactions

Market research involving 600 interviews carried out in two waves during the project revealed enthusiastic reaction from consumers to the new product range. Consumers strongly supported the idea of replacing conventional plastic packaging with bioplastics (Table 1). They also liked the idea of composting in order to close the material cycle. More than 80% of customers who purchased products in biopackaging were (very) satisfied with the performance of the packaging and 89% stated they would buy them again.

| TABLE 1. Results of market research: what do you think about replacing conventional plastic packaging with compostable biopackaging? | |

| Opinion | Respondents (%) |

| 1 (very good) | 45 |

| 2 | 44 |

| 3 | 9 |

| 4 | 1 |

| 5 | 0 |

| 6 (very bad) | 1 |

Several people even stated that they would spend more money on a product if it was packaged in bioplastics. Although this statement might be questioned in many cases, it does provide evidence that customers (especially those of high-priced products) might be willing to spend a little bit more for an environmentally friendly packaging. But this is provided the additional costs of the packaging are not shown separately but included in the price of the product.

Especially interesting was the response when people were asked to compare compostable plastic packaging to other types of material in terms of environmental friendliness. Bioplastics were ranked as even more environmentally friendly even than returnable glass packaging – a surprising result given that the latter is usually considered by far the most environmentally friendly option (Table 2).

Waste management in the Kassel project

Certified compostable packaging and biowaste were collected from households in biobins and shipped to a composting plant in Göttingen. Biowaste from Kassel has been processed here since its separate collection was introduced in 1994. In this respect, Kassel ranks about average in Germany, where around 80% of the municipalities provide an extra biobin to inhabitants. Although biobins tend not to have been introduced in areas such as big cities with a high density of population, about 70% of German citizens have access to a biobin.

| TABLE 2. Results of market research: how environmentally friendly do you think the following packaging materials are? | |

| Packaging material | Respondents who rate excellent or good (%) |

| Bioplastics | 93 |

| Glass (returnable) | 91 |

| Paper | 82 |

| Glass | 63 |

| Metal | 16 |

| Plastics | 7 |

In the Kassel project, the municipal waste hauler Stadtreiniger Kassel and the waste management service company Interseroh GmbH were responsible for organizational and educational matters. Scientific studies by the Bauhaus University of Weimar included comparisons of biowaste quality before and during the project: every four to six weeks, the waste was sorted and analysed with respect to six different fractions.

No increase in ‘missthrows’ (i.e. materials being placed in the biobin that should not be there) was observed during the trials. On the contrary, they dropped slightly at one phase during the trial. This had been anticipated by some experts and goes some way to proving that once compostable plastics are introduced into the marketplace, missthrows can be avoided if appropriate measures are taken.

| TABLE 3. Consumers’ chosen disposal routes for the bioplastic packaging | |

| Disposal route | Consumer choice (%) |

| Residual waste | 10 |

| Green Dot | 6 |

| Biobin | 59 |

| Home composting | 25 |

Germany already makes considerable efforts to recover waste, and existing collection schemes have good recovery rates. Householders’ acceptance of a ‘new system’ for the disposal of certain plastics was therefore an important issue. However, it can be concluded that, based on an existing collection system (biobin), consumers were willing to differentiate plastic packaging and dispose of the two different types separately.

During the project, approximately 85% of the bioplastic packaging was treated biologically, including 25% home composting (Table 3). The final compost was applied on fields close to Kassel and had no distinguishable differences from compost prepared without bioplastic input.10

All the results seem to support the idea of introducing a collection of certified compostable packaging using an existing biobin system. There was early criticism about the limited range of products available with compostable packaging in the shops (predominantly compostable carrier bags and fruit and vegetable packaging). However, it should be pointed out that the situation in Kassel provided a realistic picture of how this new kind of packaging would be introduced into the marketplace.

|

Customers may be willing to pay more for environmentally friendly

packaging

|

MARKETS AND APPLICATIONS

More or less in parallel to the Kassel project, compostable packaging was introduced into shops in other countries without further scientific evaluation. Most projects started during 2002 when, in the UK, Sainsbury’s and Tesco supermarkets began their first attempt with the slogan ‘organic food comes in organic packaging’. Since then, the range of applications has broadened with applications increasing by some 30%–50% per year – although at several thousand tonnes, annual amounts are still small compared with traditional plastic packaging.

Biopackaging is increasingly being used in the food sector worldwide

As in other European countries when compostable packaging was introduced to the market, a round-table has been set up in the UK. In the UK Compostable Packaging Group (UKCPG), stakeholders from industry, trade, science and officials from government departments and agencies meet to develop a common consensus for the controlled introduction of compostable packaging to the UK market and the related waste management issues. Like Germany and the Netherlands, the ‘compostable logo’ represents a basic communication tool in UK, where the Composting Association provides the certification and the logo.11

Similarly, an increase in use from a comparatively low basis can be observed in all countries where retailers have begun to feature compostable packaging. One exception is the Netherlands, where growth rates are significantly higher and companies in the food and vegetable sector are preparing for the complete replacement of conventional plastics by compostable packaging. Some of these Dutch companies also deliver to several countries in central and western Europe.

Bioplastic bags for carrots are used at Albert Heijn supermarkets in the Netherlands

The Netherlands represents a good example of a pragmatic implementation strategy where all the stakeholders were invited to participate in a round-table approach. After reviewing the Kassel results and testing that products certified according to EN 13432 could be processed in Dutch composting plants, a decision was taken to implement the same certification model and open up the biobin to compostable packaging in a stepwise approach. Initially bioplastic bags were allowed, then carrier bags were added and finally, from early 2005, all kinds of certified compostable packaging are allowed. Consumers will be informed about the innovation in a communications campaign prepared by the Belangenvereniging Composteerbare Producten Nederland (BCPN; the Dutch division of the bioplastics associations) in co-operation with VNG, the Dutch association of municipalities.

Italy and Switzerland represent countries where compostable packaging has been introduced for some years – one after the other and without ‘official’ communication campaigns (in the case of Switzerland, with a ‘round-table’ approach). The leading retail chain Migros in Switzerland started to use compostable bags for carrots and potatoes in 2002 and has since extended the product range to compostable catering products, while Italy’s Esselunga and Iper markets have been using bioplastics for shopping bags and packaging for pasta and salad.

|

85% of the bioplastic packaging was treated biologically

|

THE PICTURE IN GERMANY TODAY

When the Kassel project ended in spring 2003, very little happened in German supermarkets due to the high costs of the new kind of packaging and the complicated legislation calling for a nationwide collection system. The only existing system – the Green Dot system – does not offer specific services for compostable packaging but charges the same fee as for traditional plastic packaging (i.e. around E1.20/kg). As compostable packaging currently costs more than conventional packaging, this means an additional burden to interested companies. (For more information on the Green Dot, see WMW January–February 2005.)

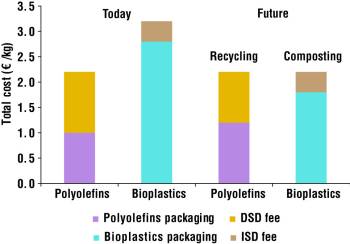

Figure 2. German waste management costs for compostable and conventional plastic packaging. DSD = Green Dot System; ISD = Interseroh

Based on the Kassel experience, there are efforts to implement a collection system using the biobin. This will result, in the long run, in costs of around E0.40/kg, thus supporting the use of compostable packaging. In addition, the increasing production of bioplastics means that their prices will fall whereas the prices for conventional plastics are expected to continue to rise. Given the cost-effective recovery for bioplastics, compostable packaging will probably be economically competitive in the near future (Figure 2).

The German Parliament (the Bundestag) and the Assembly of the German States (the Bundesrat) have approved a regulation in the German packaging ordinance granting far-reaching privileges to certified compostable packaging, and thus enabling a collection system to be implemented in parallel to the increasing amounts being used. Market experts expect an almost immediate and fast-growing market for compostable packaging in Germany. All the large retail chains have prepared for the introduction of compostable packaging – ALDI’s carrot bag test in late 2004 in southern Germany is only one example.

A good example of the rising interest is the additional ‘bioplastics’ show at the world’s biggest packaging trade fair ‘Interpack 2005’ (www.interpack.com) in Duesseldorf, Germany (21–27 April 2005). Based on a special agreement with the trade fair, some 25 exhibitors will present the latest status of the technology and describe the development of the technical framework during several workshops.

JUST A MATTER OF TIME

Al fresco: Italian supermarkets have been using bioplastic for packaging salads

Compostable plastics and packaging are ready for the market. In many applications in the food sector (especially for fruit and vegetables), increasing amounts are being used in a number of EU countries and worldwide. The technical and legislative framework has been developed at European and international levels. It seems possible to recover certified compostable plastics in composting plants without changing the process, and customers react positively to this innovative type of packaging. It therefore seems just a matter of time before this technology conquers a significant market share.

Jöran Reske is a Biologist at Interseroh GmbH. He also serves as

the Vice Chair of IBAW International Biopolymer Association, a Berlin-based

association with some 35 member companies worldwide.

Fax: +49 2203 9147 252

e-mail:

j.reske@interseroh.de

web:

www.ibaw.org

NOTES

- Witt, U. et al., Biodegradable polymeric materials – not the

origin but the chemical structure determines biodegradability.

Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 38 (10), 1999. pp. 1438–1442.

- European Parliament and Council Directive 94/62/EC of 20 December 1994

on packaging and packaging waste. Official Journal, L365,

31/12/1994, pp. 10–23; and Directive 2004/12/EC of the European Parliament

and of the Council of 11 February 2004 amending Directive 94/62/EC on

packaging and packaging waste. Official Journal, L47, 18/2/04, pp.

26–32.

http://europa.eu.int/scadplus/leg/en/lvb/l21207.htm

- BS EN 13432 (Working Group CEN TC261 SC4 WG2), ASTM D6400–03 (WG ASTM

D-20.96), DIN V 54900

(WG DIN FNK AA 103.3).

- BS EN 13432:2000 Packaging. Requirements for packaging recoverable

through composting and biodegradation. Test scheme and evaluation criteria

for the final acceptance of packaging. BSI, 2000.

http://www.bsi-global.com

-

Environment and Sustainable Development: BIODEGRADABLE AND COMPOSTABLE

POLYMERs [accessed 1 March 2005]

- Reske, J. Development of an international network for the

certification of compostability. Invited lecture given to the Annual

Meeting of the Environmentally Biodegradable Polymer Association Taiwan

(EBPA), held Taichung, Taiwan, December 2003.

- Reske, J. Biodegradable polymers in Europe: framework, applications

and market development. Invited lecture given to 8th World Conference on

Biodegradable Polymers and Plastics, held Seoul, June 2004.

- Reske, J. Market introduction of compostable packaging.

In: Biodegradable polymers and plastics, E. Chiellini (editor). Kluwer Academic, 2003.

- Estermann, R. Introducing the biodegradable bag into Switzerland’s

organic waste collection. Waste Management World, November/December

2003. pp. 62–66.

- Klauss, M. and Bidlingmaier, W. The Kassel project – use and

recovery of biodegradable polymer packaging.

www.modellprojekt-kassel.de/eng/seiten/home_eng_frameset.html [accessed 1 March 2005] - www.compost.org.uk/dsp_news_detail.cfm?id=170&link=news [accessed 1 March 2005]