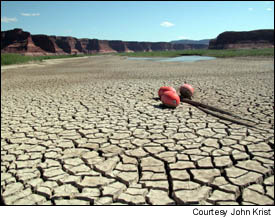

Resting on the dry lake bed, channel markers indicate the former location of Hite Marina at the upstream end of Lake Powell. Severe drought throughout the West has dropped the lake level 117 feet and brought renewed calls to drain the reservoir permanently. |

— John Wesley Powell, The Exploration of the Colorado River and its Canyons

PAGE, Arizona — Maintenance workers at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area are playing tag with Lake Powell. Each time they think they have it cornered, it slips away again.

The worst drought in the recorded history of the western United States has shrunk the lake behind Glen Canyon Dam to its lowest point in more than 30 years, leaving a 117-foot-high bathtub ring of white mineral deposits on the ruddy shoreline cliffs. To keep pace with the reservoir's steadily receding shoreline, the National Park Service has poured hundreds of cubic yards of concrete to extend marina boat-launch ramps twice in the past two years.

At Wahweap, the lake's most heavily used marina, the ramp is now about 1,300 feet long, according to Park Service spokeswoman Char Obergh. It is a vertigo-inducing slab of monumentally proportioned pavement and would seem a strong contender for the title of Longest and Steepest Boat Ramp in North America if not for the fact that another ramp at Lake Powell, the one at Bullfrog Marina, has been extended to 1,568 feet — nearly one-third of a mile.

Elsewhere at the lake, the Park Service has admitted defeat. Near the upstream end of the 186-mile-long reservoir, crews packed up Hite Marina last winter and hauled it away. Storage in Lake Powell has fallen to 42 percent of capacity, the lowest level since it was first filled, and a weedy landscape of fissured mud fills the canyon where Hite's docks once floated on sparkling water.

The record-setting drought, now in its sixth year in some parts of the West, has done more than inconvenience boaters at Lake Powell, the nation's second-largest artificial reservoir. It has thrown a scare into water managers in several states, asking them to confront the possibility that the explosive urban growth of the past 20 years in the region rests upon a hydrological mirage.

It is beginning to drive farmers and ranchers off the land in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. It threatens power shortages and price spikes this summer in California, as anemic flows curtail hydroelectricity generation in the Pacific Northwest.

The drought also has begun resurrecting the labyrinthine canyon system drowned nearly four decades ago by the rising waters of Lake Powell, revealing to a new generation of westerners the environmental cost of their water and power. And by doing that, the drought has reinvigorated a quixotic campaign to decommission the last of America's high dams and to drain forever the symbolically potent and paradoxically beautiful lake it created.

"The drought is showing us why we don't need Glen Canyon Dam," said Chris Peterson, executive director of the Glen Canyon Institute. "It's showing us what was lost when Glen Canyon Dam was built."

How Dry Is It?

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the period since 1999 has been the driest in the Colorado River watershed since the agency began keeping track of such things 98 years ago. That means the interior West is drier now than it was during the catastrophic Dust Bowl drought of the 1930s, the worst of the 20th century, when crops failed across the Great Plains and farm families fled by the thousands.

"This is the worst drought in the history of the river," said Barry Wirth, regional public affairs officer for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

California's winter precipitation and reservoir storage were about 90 percent of average, but the peculiarly warm and dry spring caused the Sierra Nevada snowpack to melt twice as fast as usual. Water managers for the state said then the summer stream flow — critical for refilling reservoirs during irrigation season — would be only 65 percent of average this year.

Nearly everywhere else in the West, the situation is much worse. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, a report on nationwide conditions produced by a consortium of government agencies and academic institutions, virtually the entire West is gripped by conditions that range from "abnormally dry" to "exceptional drought," the most severe category on its scale.

The Drought Monitor posts a map on its Web site using colors from yellow to dark red to indicate increasing levels of severity; the map presents a West with a giant vermillion bulls-eye centered about where Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming meet, with colorful ripples of bad news propagating across adjoining states.

The Natural Resources Conservation Service, a federal agency that monitors water conditions across the nation, reported May 27 that despite flurries of rain and late snowfall this spring in several western states, the Rocky Mountain snowpack melted much earlier than usual this year. The agency predicted that stream flows this summer would be near historic low levels in much of the West.

And California has little reason to be smug, despite its only slightly sub-par winter precipitation. The state relies heavily on imports from the drought-shriveled Colorado River, source of more than half the water consumed in Southern California. Although the drought has not yet interfered with Southern California water imports, Interior Secretary Gale Norton warned earlier this year of potential reductions in deliveries if the drought continues.

California also relies on hydropower generated by the Colorado and in the Columbia River basin of the Pacific Northwest. The Bonneville Power Administration, which markets the electricity produced at 31 federally owned dams in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana, recently notified California energy managers that because of low river flows — the volume in some waterways is only 40 percent of average — they should not count on being able to purchase surplus electricity from the Pacific Northwest to meet daily power needs this summer. California utilities traditionally have employed that strategy to get over the hump when energy use peaks because of air conditioner use.

Losing access to surplus power from the Pacific Northwest could mean higher electricity prices in California, as utilities turn to expensive purchases on the spot market to offset potential shortages. It may also result in increased air pollution, as generating plants that burn natural gas and coal ramp up operations to offset reductions in relatively clean hydroelectric power.

Get Used to It

There's no reason to expect things to improve in the short term, climate experts warn. In fact, there's a chance they'll get worse — a lot worse.

"The drought in the interior West will persist through summer, as the water supply situation stays the same or worsens in coming months due to below-normal snow accumulation during the winter season," the National Weather Service's Climate Prediction Center concluded in its drought forecast issued May 20. "The summer thunderstorm season during July and August will likely bring no more than short-term relief from dryness, and the long-term hydrological drought should persist at least until next winter's snow season."

Although the drought may be the most severe that has struck the West in the century that records have been kept, it is not nearly the worst the region has experienced. Scientists studying the records of climate and weather preserved in ancient tree rings, lake sediments, and fossil pollen have come to believe that the 20th century was unusually wet by long-term standards. If that's true, it means broadly held assumptions about the region's water supply, and its capacity to support farms and cities, are dangerously inaccurate.

The drought of the 1930s lasted eight years, depopulated huge swaths of the Great Plains, and was the longest to strike North America in three centuries. But droughts lasting even longer — in some cases, for several decades at a time — have occurred repeatedly in the past 2,000 years, according to climate researchers. One such extended drought is believed responsible for the disappearance of the Anasazi, ancestors of modern Pueblo tribes, from the Four Corners area of Utah, Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico in the 13th century.

"The occurrence of such sustained drought conditions today would be a natural disaster of a magnitude unprecedented in the 20th century," according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Paleoclimatology Program.

Chasing Water

At Lake Powell, where the broad white bathtub ring on the tall red cliffs is among the most obvious signs of drought in the Colorado River watershed, the National Park Service has tried to put the best face on matters.

"Fishing is great and getting better!" the agency cheerfully asserts in its latest report on lake conditions, presumably because the fish population is now squeezed into less than half its accustomed habitat.

The Park Service — which manages the lake and Glen Canyon National National Recreation Area, a 1.3-million-acre expanse of canyons and plateaus surrounding the reservoir in Utah and Arizona — spent more than $2 million last year extending launch ramps and upgrading marina utilities to cope with the falling water level. In her latest annual report, Glen Canyon Superintendent Kitty L. Roberts estimated $2.8 million would be spent on similar work in 2004. (The entire budget for Glen Canyon National Recreation Area this year is $9.3 million.)

Despite reassurances by the Park Service, and despite the fact that there's plenty of water for boats in most of the lake, tourism at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area has been dropping steadily since the drought's effects became noticeable, from 2.4 million visitors in 2001 to 2.1 million in 2002 and 1.9 million last year. Park managers attribute some of the decrease to the nationwide drop in travel after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, but they suspect widespread publicity about the falling water level at Lake Powell has contributed.

A decline in Lake Powell recreation is bad news for the economy of Page, established in 1957 as a construction camp for the crews that built Glen Canyon Dam. Named for John Chatfield Page, commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation from 1937 to 1943, the city of about 6,800 people now serves as headquarters of a lake-related tourism industry: motels, restaurants, gas stations, boat brokers, repair shops, guide services, boat rentals, fishing gear retailers.

Lake-related tourism accounts for 69 percent of the jobs in Page, according to Joan Nevills-Staveley, executive director of the Page-Lake Powell Chamber of Commerce & Visitors Bureau.

"Needless to say, if there were no Lake Powell, there would be no Page," Nevills-Staveley said. "It would be a very barren, very dismal scene."

Higher-than-normal vacancy rates, which business owners blame on news about the drought, have prompted motels in Page to discount room rates as much as 25 percent this summer, according to the chamber.

Although alarming to many, the accelerating contraction of Lake Powell is not bad news to everyone. In fact, many environmentalists and lovers of the rugged canyon country believe the only thing better than a smaller Lake Powell would be no Lake Powell at all.

The Concrete Compromise

Built and operated by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Glen Canyon Dam is a 10-million-ton plug of gracefully arched concrete wedged into a narrow canyon of Navajo sandstone. It is 710 feet tall from foundation to crest and backs up a reservoir that, when full, holds 26.2 million acre-feet. In the United States, only Hoover Dam is taller; only Hoover's reservoir, Lake Mead, is larger. (An acre-foot, 325,9000 gallons, is a year's supply for two average Southern California households.)

Glen Canyon was named by Maj. John Wesley Powell, one-armed Civil War veteran and leader of the first exploring party to travel by water through the heart of the canyon country. His party of 10 men departed Green River, Wyoming, on May 24, 1869, piloted four fragile wooden boats down the Green and Colorado rivers, and emerged three months later below the Grand Canyon.

Glen Canyon Dam and the lake named for Maj. Powell are the subjects of regret, antipathy, even hatred, in the hearts of many American environmentalists. The dam's approval by Congress as part of the Colorado River Storage Project — a series of high dams in the river's upper basin, including Flaming Gorge Dam on the Green River in Utah, Navajo Dam on the San Juan River in New Mexico, and the Wayne Aspinall Unit (Blue Mesa, Crystal, and Morrow Point dams) on the Gunnison River in Colorado — came during a ferocious debate in the late 1950s about the future of the West, the integrity of the national park system, and the proper balance between preservation and exploitation of the nation's resources.

As originally proposed by the Bureau of Reclamation, the Colorado River Storage Project was to include dams that would have flooded Dinosaur National Monument on the Utah-Colorado border. Led by the Sierra Club, environmentalists fought off those dams, but the price of victory was their agreement to drop opposition to the remainder of the project, including Glen Canyon Dam.

Those involved in the battle, notably David Brower, the Sierra Club's executive director at the time, later came to rue that compromise; when diversion tunnels around the dam were plugged in 1963, the rising water inundated a canyon complex that many who lived or traveled in the area regarded as the most lovely in the Southwest.

"The loss of beautiful Glen Canyon due in part to my own inaction is one of my biggest regrets," Brower wrote in a 1999 fund-raising letter for the Glen Canyon Institute, which was established in 1995 with the goal of decommissioning Glen Canyon Dam. "But what is lost does not have to remain so."

Costs and Benefits

Wary of being dismissed as impractical dreamers, environmentalists have for the past decade focused on cold facts and figures in making the case for Lake Powell's elimination. (In their scenario, the dam would remain but new diversion tunnels would be drilled through its flanking cliffs to let the river flow freely around it.)

Some of their assertions draw little dispute from the Bureau of Reclamation and other defenders of the dam. Both sides in the debate agree that Lake Powell traps millions of tons of sediment each year and that the Colorado below the dam has been transformed from a warm and muddy river into one that is cold and clear. In consequence, beaches and sandbars have vanished from the Grand Canyon, eliminating not only camping spots for river runners but also wildlife habitat, and several species of native fish have been driven to extinction or its brink. Elimination of the huge floods that used to tear through the canyon each spring has allowed exotic plants such as tamarisk and Russian thistle to invade the river banks, displacing native vegetation.

Both sides also agree that prodigious quantities of water are lost from Lake Powell to evaporation — 2 to 3 percent of its volume annually, according to the bureau, which amounts to as much as 800,000 acre-feet when the lake is full. That's more than the annual consumption of Los Angeles.

Where the two sides part company most dramatically is on the benefit side of the equation. The bureau characterizes Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell as critical components of the West's plumbing and power system, generating 5 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity annually (enough for 400,000 households) and allowing water managers to store sufficient runoff during wet years to ensure adequate supplies for downstream users in California, Nevada, and Arizona when drought — such as the one now gripping the region — inevitably strikes.

"If there ever was a period of time that demonstrated the critical nature of and need for Lake Powell, now is the time," said Wirth, who works in the Bureau of Reclamation's Upper Colorado River Region office in Salt Lake City. "Without Lake Powell, without Lake Mead, without the Colorado River Storage Project, we wouldn't have made it to this point."

Opponents of the dam argue that Lake Mead stores enough water for most purposes and that, even in drought, there has been enough water in the Colorado River to provide the legally mandated deliveries to states that share the watershed. If more storage is needed, they argue, it should be developed in underground basins and offstream reservoirs in the states that need it.

They also contend that the West would not miss Glen Canyon Dam's kilowatts, which account for less than 3 percent of the region's generating capacity.

Numbers, however, only take the discussion so far. Ultimately, the argument in favor of draining Lake Powell comes down an aesthetic and emotional one. To get a feel for that aspect of the debate, you can buy a book.

Writer Wallace Stegner called Glen Canyon "the most serenely beautiful of all the canyons of the Colorado River" in his 1965 essay "Glen Canyon Submersus," which is collected in a volume titled The Sound of Mountain Water.

A Utah publisher recently issued a new edition of The Place No One Knew, a large-format volume of images by noted landscape photographer Eliot Porter, originally published by the Sierra Club in 1963 as a eulogy for the doomed canyon. You also can read Ed Abbey's classic book Desert Solitaire, which includes a mournful essay recounting a float trip through Glen Canyon in the final days of dam construction. Or you can take a hike.

A Canyon Reborn

From just east of the hamlet of Escalante in southern Utah, the unpaved Hole in the Rock Road carves its way across 60 miles of corrugated stone and drifting sand, paralleling the steep escarpment of the Kaiparowits Plateau to the west and the hidden Escalante River canyon to the east. The road terminates above the Colorado River at a notch blasted and hacked into the canyon wall in 1880 by Mormon settlers seeking a shortcut to southeastern Utah. At intervals, spurs branch off the dirt road toward the Escalante, eventually fading into trails that switchback into the main canyon.

At one such trailhead in late May, guide Travis Corkrum of Salt Lake City, Utah, and freelance photographer Eli Butler of Flagstaff, Arizona, met a group of backpackers who had signed up for a four-day trip sponsored by the Glen Canyon Institute. Shouldering packs, the group of eight hikers trudged across sand and slickrock, past blooming beavertail cactus and sage, to the edge of the plateau.

At the lip of the 900-foot-deep canyon, the route required hikers to clamber down a vertical rock face and then squeeze through a crack in the rock barely wide enough for an average adult. The packs had to be lowered by rope. Gathering again at the bottom of the cliff, the group descended a steep slope of shifting sand and dropped into the inner canyon, setting up camp on a sandy bench beneath an overhanging wall of sandstone.

For four days, the group explored Coyote Gulch and lower Escalante Canyon, parts of which had been inundated by Lake Powell until a year earlier. The retreating water has reopened hundreds of miles of narrow canyons to foot traffic, revealing seeps and springs, alcoves carpeted with maidenhair fern and columbine, quiet pools reflecting burnished slickrock.

Upstream in Coyote Gulch and Escalante Canyon, in areas untouched by the lake, lie additional reminders of what drowned when the reservoir filled: whispering groves of cottonwood and willow trees, grassy flats where Anasazi farmers — their abandoned granaries and panels of rock art still visible high on the cliffs — grew corn, beans, and squash a thousand years ago. There are arches and bridges carved from stone by time and running water, gnarled oaks, waterfalls, monolithic walls varnished with a natural patina of blue-black iron and manganese.

There is deep silence within the canyons. Although water flows year-round from springs in Coyote Gulch and in the Escalante River, it does so silently, slipping across the sandy canyon floor with barely a murmur. The loudest sounds are those of dripping seeps, trilling canyon wrens, and the splash of hikers' footsteps as they wade in the water, which in mid-May was ankle-deep in Coyote Gulch and sometimes reached mid-thigh in the Escalante.

It is these intangible qualities of the drowned but partially resurrected canyon complex — silence, antiquity, the spectacle of green life, and flowing water in a rocky desert — that environmentalists believe offer the most compelling argument against Lake Powell. By organizing backpacking trips into the area, directors of the Glen Canyon Institute hope to use the power of the landscape itself to swell the ranks of antidam activists.

"That's what's going to win this campaign: that permanent place in your heart that this place holds," Peterson said.

Past and Future

Weighed against the aesthetic and emotional values of a restored canyon system are kilowatts, the stark beauty of Lake Powell itself, the reservoir's popularity with boaters and consequent economic value to Page, and the flexibility the dam and lake give to Western water managers charged with the difficult task of keeping cities and farms alive in very dry places.

"The reality is that it (Lake Powell) will refill: It has to refill," Wirth said. "We have no other way to prepare for the next drought that's going to come."

In Page, chamber director Nevills-Staveley has some sympathy for those who would like to see the canyons resurrected. She's the oldest daughter of Norm Nevills, who in the 1930s launched one of the first commercial rafting businesses on the Colorado River and helped give birth to what has become a major recreational industry. His pioneering 1938 excursion through Glen Canyon and the Grand Canyon, at a time when fewer than 100 people had managed the feat, drew nationwide press attention and made him famous. Before his death in a 1949 plane crash, Nevills led many commercial trips through Glen Canyon, and his daughter remembers it well and fondly.

However, she believes that even if Lake Powell were drained, the wild, lonely, and beautiful canyon she remembers exploring in the days before the dam is unlikely to return to its natural state — certainly not in her lifetime, nor in the lifetime of anyone now living. Besides, she said, the lives of too many people in Page and on the neighboring Navajo Reservation have, for better or worse, become inextricably tied to the reservoir in the past 40 years.

"You can't go back," she said.

While the pro-dam and antidam forces marshal their arguments, battling for the hearts, minds, and perhaps the soul of the West, a third participant in the debate — nature — likely will have the final say.

If rain and snowfall return to average in the Colorado River watershed, it will take at least a dozen years to refill Lake Powell, Wirth said. If the drought continues and the reservoir keeps dropping at its curent pace, in as little as two years the water in Lake Powell will drop below the turbine intakes and Glen Canyon Dam's massive generators will shut down.

A journalist for more than 20 years, John Krist is a senior reporter and columnist at the Ventura County Star in Southern California and a contributing editor for California Planning & Development Report. His weekly commentaries on the environment are distributed nationally by Scripps Howard News Service, and he is a regular contributor to Writers on the Range, a syndicated service of High Country News, which distributes commentaries to more than 70 newspapers in the West.

Send comments to feedback@enn.com.

Related Links

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

Glen Canyon Institute

Page-Lake Powell Chamber of Commerce & Visitors Bureau

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Upper Colorado River Region

Natural Resource Conservation Service's National Water and Climate Center

National Weather Service Cimate Prediction Center

NOAA Paleoclimatology Program

U.S. Drought Monitor