|

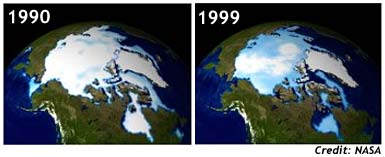

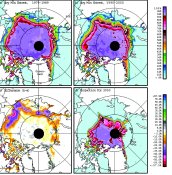

November 27, 2002 THE ARCTIC PERENNIAL SEA ICE COULD BE GONE BY END OF THE CENTURYA NASA study finds that perennial sea ice in the Arctic is melting faster than previously thought—at a rate of 9 percent per decade. If these melting rates continue for a few more decades, the perennial sea ice will likely disappear entirely within this century, due to rising temperatures and interactions between ice, ocean and the atmosphere that accelerate the melting process. Perennial sea ice floats in the polar oceans and remains at the end of the summer, when the ice cover is at its minimum and seasonal sea ice has melted. This year-round ice averages about 3 meters (9.8 feet) in depth, but can be as thick as 7 meters (23 feet). The study also finds that temperatures in the Arctic are increasing at the rate of 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.2 Fahrenheit) per decade. Melting sea ice would not affect sea levels, but it could profoundly impact summer shipping lanes, plankton blooms, ocean circulation systems, and global climate. “If the perennial ice cover, which consists mainly of thick multi-year ice floes, disappears, the entire Arctic Ocean climate and ecology would become very different,” said Josefino Comiso, a researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md., who authored the study. Comiso used satellite data to track trends in minimum Arctic sea ice cover and temperature over the Arctic from 1978 to 2000. Since sea ice does not change uniformly in terms of time or space, Comiso sectioned off portions of the Arctic data and carefully analyzed these sections to determine when ice had reached the minimum for that area each year. The results were compiled to obtain overall annual values of perennial sea ice. Prior to the complete data provided by satellites, most records came from sparsely located ocean buoys, weather stations, and research vessels. The rate of decline is expected to accelerate due to positive feedback systems between the ice, oceans and atmosphere. As temperatures in the Arctic rise, the summer ice cover retreats, more solar heat gets absorbed by the ocean, and more ice gets melted by a warmer upper water layer. Warmer water may delay freezing in the fall, leading to a thinner ice cover in the winter and spring, which makes the sea ice more vulnerable to melting in the subsequent summer. Also, the rise in summer ice temperatures by about 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.2 Fahrenheit) each decade could lengthen the summers, allowing earlier spring thaws and later freeze dates in the fall, causing further thinning and retreat of perennial ice. Comparing the differences between Arctic sea ice data from 1979 to 1989 and data from 1990 to 2000, Comiso found the biggest melting occurred in the western area (Beaufort and Chukchi Seas) while considerable losses were also apparent in the eastern region (Siberian, Laptev and Kara Seas). Also, perennial ice actually advanced in relatively small areas near Greenland. In the short term, reduced ice cover would open shipping lanes through the Arctic. Also, massive melts could increase biological productivity, since melt water floats and provides a stable layer conducive to plankton blooms. Also, both regional and global climate would be impacted, since summer sea ice currently reflects sunlight out to space, cooling the planet’s surface, and warming the atmosphere. While the latest data came too late to be included in the paper, Comiso recently analyzed the ice cover data up to the present and discovered that this year’s perennial ice cover is the least extensive observed during the satellite era. The study appears in the late October issue of Geophysical Research Letters, and was funded by NASA’s Cryospheric Sciences Program and the NASA Earth Science Enterprise/Earth Observing System Project. The mission of NASA’s Earth Science Enterprise is to develop a scientific understanding of the Earth System and its response to natural or human-induced changes to enable improved prediction capability for climate, weather and natural hazards. ###Contact: Krishna Ramanujan Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Md. 20771 (301) 286-3026 |

Perennial Ice

Perennial Ice

Albedo

Albedo