By Bill Brocato

In the not-so-distant past, when oil rigs drilling for black gold in

Europe and the U.S. also brought natural gas to the surface, their

operators were instructed to do something that would be unthinkable today:

flare it off. Because there was little demand for the hydrocarbon then,

the tactic made sense. After all, the oil majors reasoned, if no one

wanted or was willing to pay for methane, why spend anything to collect

it?

Those days are gone. In fact, demand for natural gas has grown so much in

recent years that it may even depose King Crude on the world energy stage.

Gas has become the fuel of choice for power plants in developed countries

because burning it produces less pollution (in the form of nitrogen

oxides, sulfur dioxide, and particulates) than burning oil and far less

pollution than burning coal.

Burning natural gas rather than oil or coal also reduces a power plant’s emissions of the greenhouse gases (primarily carbon dioxide) believed to be responsible for global warming. The European Union already has imposed CO2 caps on its member nations, and last year alone 24 U.S. states—including California, the world’s seventh-largest economy—took legislative steps to build frameworks for regulating emissions of the gas.

|

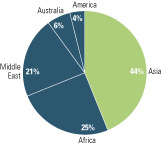

| 1. Liquefaction capacity by region, 2001 |

By themselves, these Western initiatives guarantee that natural gas will be a much stronger rival for oil in worldwide electricity production. But many believe that their decisive battle will be in the East, where pollutant and CO2 emissions from widespread burning of oil and coal are reaching hazardous levels. Bear in mind that South Asia and China are home to about 2.6 billion people—nearly half the world’s population.

However, Asia may end up providing the solution to the problem it exacerbates. Its nations have vast reserves of natural gas that could be tapped, liquefied (Figure 1), and shipped by tanker to demand centers around the world. The region already has garnered several billion dollars in economic aid from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to help with infrastructure development.

Meanwhile, energy companies are moving quickly to make more liquefied natural gas (LNG) commercially available. The oil majors BP, ChevronTexaco, Shell, ExxonMobil, and ConocoPhillips have accelerated their exploration and production (E&P) activities in the Far East to satisfy future demand. And they are investing in state-of-the-art LNG ships and processing terminals in nations too poor to make those investments themselves.

The East is in the red

According to Ken Otto, a VP of the Houston-based consultancy Purvin &

Gertz Inc., South Asia’s energy shortfalls—manifested by frequent and

widespread power outages—can largely be attributed to the region’s

inadequate natural gas transportation infrastructure. Otto contrasts the

region’s environment for gas to China’s. Since the mid-1990s, the

Middle Kingdom’s energy policies have encouraged the future use of gas

by fostering investments in E&P and transportation.

However, in East Asian countries other than China, the level of natural

gas production is currently insignificant, and a large increase is not

predicted. As a result, those countries will continue to rely on LNG

imports from Southeast Asia, Oceania, the Middle East, and North America.

Over the longer term, East Asian nations hope to satisfy domestic demand

and become major exporters by building and operating gas pipelines;

current proposals include one from Irkutsk to Korea via China and another

from Sakhalin to Japan. But as billion-dollar projects with considerable

political risk, their prospects remain uncertain.

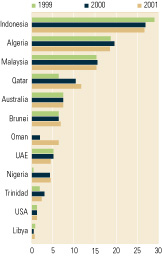

Southeast Asia and Oceania are rich in natural gas resources, but more than 70% of the regions’ total recoverable reserves are in just three countries—Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. All three have been exporting LNG mainly to East Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, reports the International Gas Union (Figure 2). However, two crucial uses for future natural gas production in the Asia Pacific region are LNG export projects and increased gas supplies to domestic markets and neighboring countries by pipeline.

Rudolf Ter-Sarkisov, director general of the Russian gas firm Vniigaz, reported at the International Gas Union’s World Gas Conference in Tokyo this past summer that Thailand, the Philippines, Myanmar, and Vietnam also are promoting natural gas development and ramping up their production of the fuel. He explained that the drivers of those separate initiatives have one thing in common: increased demand for gas by power stations.

But though Ter-Sarkisov said he expects Asian countries’ domestic demand for gas to keep rising, another driver that will play a more important role down the road is their desire to increase their LNG exports. All of the existing LNG exporters (Indonesia, Malaysia, Australia, and Brunei) have plans to expand their existing terminals, promote new LNG projects, or both. Papua New Guinea also may become an LNG exporter in the future.

|

| Ken Otto |

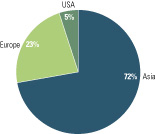

The consensus of industry experts is that the success of those new projects will increasingly depend on how much LNG emerging economies such as China and India end up importing (Figure 3). But they add that the strength of established markets beyond the Asia Pacific region—such as the west coast of the U.S.—will continue to play a role as well.

In Tokyo, Ter-Sarkisov warned that, although worldwide demand for natural gas is increasing, production trends in some countries that are its largest consumers are not very promising. “That’s why the next decade will be very important to the gas industry as it develops further,” he said. “Exploration targets must move to deeper formations, deeper waters, and more-remote areas.”

Show me the money

|

| 2. LNG exports by country during 1999, 2000, and 2001 |

However, without further development of the trading of gas as a commodity, it is entirely possible that the use of gas as a power plant fuel will be severely curtailed. According to the findings of the Working Committee 9 on Gas Prospects, Strategies and Economics presented at the World Gas Conference in Tokyo, the industry’s challenge is to meet the world’s growing demand for natural gas by expanding interregional gas trade. The committee found that to do so, it won’t suffice to report that gas is available and that there’s “lots” of demand for it. What’s also needed are answers to these questions: Can we get that gas to the marketplace? and What will it take, financially, to grow gas demand, transportation systems, and interregional trade?

The committee detailed that gas supplies would continue to increase through 2030 and that today’s gas reserves should be adequate to support current, record levels of production for the next 200 years. It found that under a “base case” scenario, world demand for gas is expected to double by 2030. Assuming an annual growth rate of 2.3%, the fuel’s share of worldwide primary energy use will reach 26.5% by 2030, up from 23.2% in 2000. Total world energy demand is expected to increase by 70% over the same period.

The use of natural gas for power generation will drive this growth. In 2000, interregional trade in natural gas represented more than 12% of world gas consumption, with 90% of exports coming from three regions: East Europe and North Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia. LNG accounted for 46% of the deliveries and gas pipelines for 54%.

|

| 3. Regional LNG markets in 2001 |

The committee believes that international trade in natural gas could triple by 2030. At constant prices, the required investment between 2000 and 2030 to realize this dramatic expansion in trade will be between $2 trillion and $3 trillion, of which more than $1 trillion will be spent on upgrading or replacing existing infrastructure. “Although this level of investment is not out of line with historic costs, the financial needs will be significant and will require the cooperation and support of governments and regulators,” the committee wrote in its report.

Meanwhile, several oil majors are betting that their investments in projects to bring natural gas to Asian countries will pay off handsomely. For example, Will Schmidt, manager of gas trading operations for ConocoPhillips in Singapore, pointed out that the company’s Bayu-Undan development is a world-class gas liquids project. Located in the Timor Sea about 500 kilometers northwest of Darwin, the project received an initial infusion of $1.8 billion in October 1999. The field is estimated to have recoverable reserves of 400 million barrels of liquids (condensate and LPG), 3.4 trillion cubic feet of gas, and a life of 25 years. The project’s first production of liquids was slated for the end of last year.