We need to turn carbon into gold

Progress at the UN climate summit in Poznan, Poland, appears to have ground to a halt.

As the global gathering enters it second and final week, there has been a dismal lack of progress to date.

One of the key stumbling blocks is how all the things that we need to tackle the climate change problem will be financed.

Here are some of the key topics being debated:

Forests and soils

Forest destruction and degradation contributes up to 20% of human greenhouse gas emissions.

But how can we bring about the change we need?

The answer has to be to make forests worth more alive than dead to governments and forest owners.

As things stand we are happy to pay for palm oil, beef, soya beans, rubber and timber from deforested land.

To persuade countries like Brazil and Indonesia to change their ways, we need to pay them more keep their forest than we are already paying them to destroy it.

Currently the main idea, which goes under the acronym of REDD, is to create carbon credits by reducing deforestation in poor countries, and selling the credits to rich countries so that they can let their industrial emissions rip.

But this suffers from the grave defect that we need to reduce emissions from both forests and industry at the same time, not trade one off against the other.

Adaptation to climate change

The cost to poor countries of the climate change that is already taking place, no matter what action we take to reduce emissions, is up to $100 billion per year.

This cost is incurred in the effort to cope with the consequences of drought, flood risk, rising sea levels, increasing insect-borne disease, and other hazards.

So far, a paltry few percent of this funding has been lined up. Since the damages are a direct result of the historic emissions of rich countries, and the world's poorest people are the principal victims, this is nothing short of iniquitous.

Meanwhile, more than $60bn-a-year is sloshing around the world's carbon markets, such as the European Union's Emissions Trading Scheme and the "flexibility mechanisms" of the Kyoto Protocol.

It sometimes seems that everyone is making fortunes out of the carbon market, except those who really need it to adapt to the far harsher conditions that climate change is creating.

Renewable energy

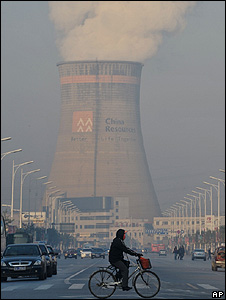

Renewable energy is a key part of any sustainable future. But developing and rapidly industrialising countries are generally choosing coal-fired power generation, because it is relatively cheap, it works, and it's available now.

Every fossil fuel power station built locks in decades of

further emissions

|

This development path will lock these nations into burning coal for up to 75 years, undermining any effort made elsewhere to reduce emissions.

This makes it essential to divert the hundreds of billions of dollars each year that are being invested in fossil fuels in developing countries and put them into renewables.

But in order to make this happen, extra funds need to be found to bridge the gap between the cost of coal fired power stations and renewables.

In the long run, renewables make good economic sense because once they are built there is no need to buy the fuel to keep them running.

But in the short term there is an extra cost to be paid and at the moment, there's no one to pick up the bill.

Energy efficiency

Vastly improved energy efficiency is absolutely necessary to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to satisfy rising demand for energy around the world.

Even though energy savings can be made for next to nothing, they tend not to take place. This is usually because the costs are picked up by one person, while another enjoys the benefits.

So how are we to stimulate the revolution we need?

One answer is to regulate. EU citizens are already aware of the "energy rating" system that applies to many household appliances, and this approach has been highly effective. It should now be extended globally to all energy consuming goods, homes, buildings, factories and offices.

Poor countries will of course need extra funding to have their short-term costs covered. But in the long term, they will also benefit from reduced energy costs.

Powerful industrial greenhouse gases

The hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are gases used as refrigerants and foam blowing agents.

They were introduced by the chemical industry to replace ozone destroying CFCs, which have (almost) been phased out by the Montreal Protocol.

However, HFCs are powerful greenhouse gases, and their production is rising by 15% per year.

The Environmental Investigation Agency estimates that without controls, they could be responsible for the equivalent of about 10 gigatonnes of CO2 emissions per year by 2040, or about one-third of the world's current burn of fossil fuels.

The obvious way to control them is in the same way that the Montreal Protocol phased out the CFCs.

This would involve a direct regulatory approach, guided by an expert panel, with funding made available to help developing nations meet the cost of adapting affected industries.

Where is the money going to come from?

Currently there is no mechanism capable of taking on the problems of climate change.

My own calculations indicate that it will cost the world about one trillion dollars each year.

That is certainly a lot of money, but it is an amount that looks affordable when it is compared to what the world is spending to deal with the global financial crisis.

One obvious way to raise the funds is to sell greenhouse gas emissions permits on a global basis, rather than giving them away as under the current Kyoto Protocol.

With industrial global emissions accounting for about 33 gigatonnes, a $30-per-tonne carbon price would pay the whole bill.

The EU is already going this way. More and more allowances under the ETS are being auctioned, and the European Parliament is calling for the proceeds to finance climate solutions.

President-elect Barack Obama has a similar national policy for the US, and a new report by humanitarian charity Oxfam calls for this model to be applied to rich country emissions allocations, with auctioning taking over from free allocations.

This general approach has to be the way forward, for the simple reason that there's nowhere else for the money to come from.

Governmental aid flows remain pathetically insufficient even to deal with all the "old" problems of poverty, never mind the new problems of climate change.

Charities are nowhere near rich enough, and the private sector will only invest where there is profit to be made.

So here is one principle for delegates in Poznan to agree on - the carbon

market must be turned into gold, not for carbon traders and financiers, but

to finance the world's transition to a low carbon, equitable future.

Oliver Tickell is author of Kyoto2 - how to manage the global greenhouse, published by Zed Books

The Green Room is a series of opinion articles on environmental topics running weekly on the BBC News website