Hopi Tribe, environmentalists work to save ancient

petroglyphs

By Bobbie Whitehead, Today correspondent

Story Published: Oct 13, 2008

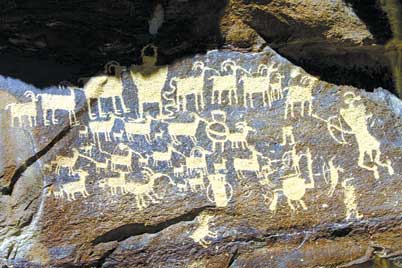

The rock images, also called petroglyphs, shown were created by ancestors of the Hopi Indians in what is now called Nine Mile Canyon in Utah. The Hopi Tribe and several environmental groups want to protect the rock art from dust created by industrial traffic heading to the West Tavaputs Plateau Natural Gas development site.

|

CHESAPEAKE, Va. – Described as an outdoor museum, Nine Mile Canyon in Utah

stands out as a unique public site filled with ancient rock art carved by

the Hopi Indians’ ancestors more than 1,000 years ago.

While the U.S. Bureau of Land Management designated Nine Mile Canyon a

National Back Country Byway, the agency also leased land on a plateau of the

federal property to a private corporation that has been drilling for natural

gas.

That drilling on the canyon’s West Tavaputs Plateau has created a cloud of

concern regarding the industrial truck traffic entering and leaving the

area.

Environmentalists and the Hopi Tribe say dust kicked up from the traffic,

the chemicals used to control the dust, jarring from the drilling and

exhaust from industrial vehicles are harming the rock art, also called

petroglyphs, and other artifacts there. And a proposed expansion of gas

production activities would worsen the situation, according to a tribal

official.

“Nine Mile Canyon is a special place that deserves special treatment as a

cultural resources preserve and not as an industrial highway,” wrote Hopi

Tribe Cultural Preservation Office Director Leigh Kuwanwisiwma in the

tribe’s review of the West Tavaputs Plateau development plan. “Because of

the potential for destruction of the nationally significant Hopi cultural

resources in and around Nine Mile Canyon, our concern for the impacts to

those resources resulting from this project cannot be underestimated.”

In the April review, he wrote that the BLM proposal for the drilling site

would add industrial traffic up to nearly “1,500 18-wheel trucks per day”

and would increase the number of wells being drilled from 38 to 807. Such

increases, he said, could only intensify the harm.

The Hopi Tribe requested that the federal Advisory Council on Historic

Preservation assist with the transition from the draft to the final

Environmental Impact Statement, a requirement by the National Environmental

Policy Act, for the proposed expansion to move forward.

The ACHP involves itself when a proposed project could result in the loss of

a historic property or damage to a property that prevents it from achieving

National Historic Landmark designation or eligibility on the National

Register.

“The council’s participation in the review is good because the BLM wants to

protect the rock art while also promoting environmentally responsible energy

development,” said Megan Crandall, BLM Utah spokeswoman.

Groups like the Colorado Plateau Archaeological Alliance say harm also comes

from the construction of new roads on federal lands that have been leased

for gas or oil well drilling. These roads leave unexplored areas open to

looters and recreational off-road vehicles.

“In the American West, most all land is federal land, and the lands are

being developed with entire areas being opened to oil development,” said

Jerry Spangler, CPAA executive director.

People enter these areas and search for valuable artifacts to sell on the

black market, he said: “Looting is common, and it’s happening often.”

Few law enforcement officers are available to stop the looters, which

exacerbates the problem, he added.

“With only 5 percent of the West’s lands having been surveyed to determine

what types of archaeology might be on them, it’s impossible to manage these

lands if we don’t know what’s there.”

The CPAA also has concerns about the thousands of ancient images etched into

the stone being covered by industrial traffic dust.

“They have a thin white powder coat on them,” Spangler said. “This could

have been avoided with proactive management.”

In August, The Wilderness Society, the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance and

the Nine Mile Canyon Coalition filed a lawsuit against the Interior

Department and the BLM.

The lawsuit alleges that Interior and the BLM failed to follow the National

Environmental Policy and the National Historic Preservation acts – which

both prohibit activities that would harm cultural, historic and

environmental resources – when they allowed the drilling of 30 wells on the

West Tavaputs Plateau.

The Wilderness Society has documented an increase in drilling permits issued

by the BLM and a decrease in environmental regulations since 2001.

“We started to see, in 2001, formal policy changes to prioritize oil and gas

drilling at the expense of everything else such as environmental concerns,

cultural resources and wildlife protection,” said Nada Culver, The

Wilderness Society senior counsel. “One of the indicators that we can track

is the agency’s own records of leasing and permits to drill.”

The largest number of drilling permits issued has been in the five Rocky

Mountain states – Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming and Montana, she said.

From 2001 to 2007, the BLM approved 32,926 permits and leased 14.3 million

acres of federal land in these five states, with a total of 35,106 permits

issued and 26.6 million acres of land leased nationwide, according to bureau

records.

“The other trend is the concept that not only do we need to make everything

available for drilling, but we need to make everything available to off-road

vehicles,” Culver said. “What these two trends have in common is they tend

to exclude other uses and damage the other resources and values of public

land.”

Crandall said the BLM at no point makes a choice between one resource and

another.

“We’re required, federally, to protect our land for natural resources. The

road through Nine Mile Canyon was built in the 1800s, and there’s been

drilling on the plateau since the 1950s.”

The BLM stopped using magnesium chloride in Nine Mile Canyon to suppress

dust since it found that chemical compound in dust from the canyon in one of

its studies, Crandall said. The company leasing the land, the Bill Barrett

Corp., is looking at other dust suppression products.

“Our main goal is to preserve the rock art while also finding a way to

support environmentally sound energy development on the plateau.”

The Hopi Tribe and others have asked the BLM to develop alternate routes to

the drilling sites to eliminate the harm caused by truck traffic. However,

the BLM dropped an alternate road option because its substantial

environmental impact and cost made it unfeasible.

© 1998 - 2008 Indian Country Today. All Rights Reserved To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.indiancountry.com