Global Warming Triggers an International Race for the Arctic

| A new epoch is beginning at the top of the Earth, where the historic melting of the vast Arctic ice cap is opening a forbidding, beautiful, and neglected swath of the planet. Already, there is talk that potentially huge oil and natural gas deposits lie under the Arctic waters, rendered more accessible by the shrinking of ice cover. Valuable minerals, too. Sea lanes over the top of the world will dramatically cut shipping times and costs. Fisheries and tourism will shift northward. In short, the frozen, fragile north will never be the same. |  |

The Arctic meltdown—an early symptom of global warming linked to the buildup

of atmospheric greenhouse gases—heralds tantalizing prospects for the five

nations that own the Arctic Ocean coastline: the United States, Canada,

Russia, Norway, and Denmark (through its possession of Greenland). But this

monumental transformation also carries risks quite aside from the climate

implications for the planet—risks that include renewed great-power rivalry,

pollution, destruction of native Inuit communities and animal habitats, and

security breaches. "The world is coming to the Arctic," warns Rob Huebert, a

leading Arctic analyst at the University of Calgary. "We are headed for a

lot of difficulties."

The vast stakes, along with some political grandstanding, are inspiring

predictions that a new great game among nations is afoot—a tense race for

the Arctic. That scenario got a shot of drama last year when two Russian

minisubmarines made a descent to the seabed beneath the North Pole and

planted a titanium Russian flag. The operation lacked any legal standing but

symbolized Moscow's claims to control the resources inside a mammoth slice

of the Arctic, up to the North Pole itself. To calm the mood, the five

Arctic coast countries gathered diplomats in Greenland this May to agree

that boundary and other disputes would be handled peacefully under existing

international law. "We have politically committed ourselves to resolve all

differences through negotiation," Danish Foreign Minister Per Stig Möller

said at the time. "The race for the North Pole has been canceled."

Or maybe just put on ice, so to speak. It is not certain that his

assertion will hold up, given the long history of great powers vying for

riches and strategic gain.

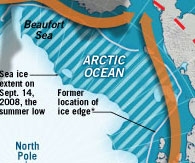

This summer, for the first time, both the fabled Northwest Passage through

the upper reaches of North America and the Northern Sea Route above Russia

opened up, apart from drifting ice. Overall, the expanse of Arctic sea ice

was the second smallest in the 30 years of monitoring (summer 2007 was the

smallest), and that left an islandlike polar ice cap surrounded by open

water. In just the past five years, summer ice has shrunk by more than 25

percent, and so has its average thickness. One consequence of this change is

that much of the sun's heat formerly reflected back out to space by the ice

sheets is now being absorbed, entrenching the warming process. The

acceleration of the ice melt is outstripping earlier predictions of a

basically ice-free Arctic summer by mid- or late century. NASA climate

scientist H. Jay Zwally now anticipates that most of the Arctic will lose

summer ice in only five to 10 years. "We appear to be going through a

tipping point," he says.

Already, the ice melt is threatening the traditional livelihoods of native

Inuit peoples from Alaska to Greenland. In Alaska, Inuit hunting has grown

more difficult because walrus herds have moved away with the receding ice.

In Greenland, where glaciers are thawing, similar dislocations are

happening, even while commercial interests undertake a "new gold rush" for

natural resources, in the words of Inuit leader Aqqaluk Lynge. The Inuits

want more say in how the High North is developed. "You have to settle things

with us," says Lynge. "We are witnessing, almost, the death of our culture

if we don't do anything."

And yet the changing Arctic is yielding big commercial opportunities. This

summer, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that the area above the Arctic

Circle, which covers 6 percent of the Earth's surface, holds 13 percent of

its as-yet-undiscovered oil and 30 percent of undiscovered natural gas—most

offshore, not on land. Energy companies are intrigued. Royal Dutch Shell,

for instance, laid down $2 billion this year for drilling leases in the

Chukchi Sea off of Alaska. BP will drop $1.5 billion to develop an offshore

Alaskan oil field, and Exxon Mobil and Imperial Oil of Canada bid $600

million for an exploratory area on the Canadian side of the Beaufort Sea.

Oil hunt. Last year, Norway's StatoilHydro showed that marauding ice

packs and perilous cold could be overcome, launching the first commercial

energy operation in Arctic waters. Norwegian tankers are now transporting

liquefied gas from the Snow White field, 90 miles above the Norwegian shore,

to Maryland's Cove Point Terminal, from which it is piped to consumers on

the East Coast. With the development of new technologies, like production

gear that sits on the bottom of the sea and reinforced tankers that can move

bow-first in open water or stern-first to break through ice, the energy

industry is readying itself for the Arctic age. "Technology will not hold up

Arctic resource development," says Geir Utskot, an Arctic executive for

Schlumberger Oilfield Services.

Fortunes may be made in other pursuits as well. The Arctic ice melt will

expose mining opportunities for commodities from diamonds and gold to

nickel, copper, and chromium. Sea temperature shifts could prompt some fish

stocks to migrate to Arctic waters newly accessible to fishing vessels.

Those vessels won't be the only ones heading north. Global cargo shipping

could change radically because of newly usable Arctic sea lanes. Sailing

over the top of the world could cut up to half the current shipping distance

between East Asian ports and Europe or the eastern United States, providing

an enormous saving in fuel costs and transit time.

Arctic tourism could also flourish. Chuck Cross, president of Bend,

Ore.-based Polar Cruises, joined about 100 of his customers in June on the

Russian nuclear icebreaker 50 Years of Victory. It set out from Murmansk, in

Russia, to the North Pole; thinning ice made the journey a fast one. At the

pole, they disembarked to picnic on the ice, though after some difficulty.

"We had to maneuver around for more than half an hour because we couldn't

find any ice big enough for those hundred people to get off the ship

safely," he says.

The nations in the new Arctic game have also been maneuvering for position.

All five either have mapped or are mapping the outward extensions of their

continental shelves. That painstaking and expensive science is critical to

making economic claims. The key piece of international law in the Arctic is

the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The United States,

though not yet a signatory, is acting as though it will be. Under the

treaty, a panel of specialists issues recommendations on where shelves end

and international seabeds begin. States are entitled to exclusive economic

rights to the sea and what lies underneath for up to 200 nautical miles off

their coasts. The area of economic control can be extended if the

continental shelf is shown to range farther.

There is much in dispute. The United States and Canada will most likely make

overlapping claims on their shelves, as will Norway and Russia. But the

biggest problem may arise from a 1,240-mile underwater mountain range called

the Lomonosov Ridge, which runs from Siberia to Greenland and Canada. All

three may claim it as the natural extension of their homelands. In addition,

the Arctic is rife with disagreements over boundaries and maritime passages.

Canada and the United States cannot agree over their maritime boundary in

the Beaufort Sea, nor on the status of the Northwest Passage. Canada

considers the passage internal, while the United States and others view it

as an international strait. Russia has not ratified a previous treaty fixing

its maritime frontier with the United States near the Alaska coast. Canada

and Denmark disagree over ownership of rocky Hans Island, and Norway and

Russia differ over drawing a line in the Barents Sea. "All the ingredients,"

says Scott Borgerson, an Arctic expert with the Council on Foreign

Relations, "are present to create an unstable situation."

Russian maneuvers. Amid that uncertainty, the Arctic nations are growing

more assertive—especially the two with the longest Arctic frontage, Russia

and Canada. The Russian flag-planting—dismissed as "a stunt" by U.S. and

other officials—appealed to the nationalist mood in Russia, with the feat

likened to the American moonshot of 1969. Asserted the expedition's leader,

explorer and parliamentarian Artur Chilingarov, "The Arctic is ours." The

Russian show drew poor reviews elsewhere, though, especially in Canada.

"This isn't the 15th century," retorted then Foreign Minister Peter MacKay.

"You can't go around the world and just plant flags and say, 'We're claiming

this territory.' "

Russian officials say it was not a claim but rather part of a research

voyage to chart the continental shelf. But Moscow's ambitions for the Arctic

are raising anxieties. Last month, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev

convened his Security Council to discuss the "strategically important"

Arctic. He called for a law to set Russia's southern Arctic zone and

described the pursuit of Russian interests there as a "duty to our

descendants." With more than 20 icebreakers, seven powered by atomic

reactors, Russia has unparalleled capabilities in the Arctic.

"Geographically, they're far and away the dominant force up there," says

Arctic expert Borgerson, a former Coast Guard officer. Russia conducted two

scientific expeditions in the Arctic this past summer and has stepped up

naval activity there. Its strategic bombers and reconnaissance planes have

also flown over Arctic waters near Alaska, Canada, and Norway.

In Canada, meanwhile, the government has also struck a tough tone, appealing

to nationalist sensitivities. That tack has political benefit, especially as

the ruling conservatives stand for re-election this month. A strand of the

Canadian identity has always revered the great white north: "The true North,

strong and free! From far and wide, O Canada, we stand on guard for thee,"

goes the country's national anthem.

After the Russian flag planting, Ottawa seemed primed to take up the

challenge. " 'Use it or lose it' is the first principle of sovereignty in

the Arctic," says Prime Minister Stephen Harper. He has portrayed the region

as a key to future Canadian prosperity. His government has decided to

double, to 200 nautical miles from the coast, its jurisdiction over shipping

and plans to spend $100 million on geomapping over the next five years. On

the military side, it is running annual Arctic "sovereignty exercises" and

will establish a cold-weather training center at Resolute Bay and a

deep-water port. Canada's Navy will also acquire eight more ice-strengthened

patrol ships.

The United States, for its part, has not acted with the same urgency. "We

are behind when it comes to what is happening with our other Arctic

neighbors," says Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. The lagging

begins with the Law of the Sea convention. Despite Bush administration

support, Senate ratification of the 1982 treaty remains blocked by

conservative Republicans fearful that the treaty will give away American

sovereignty. The other four Arctic coastal states have adopted the

convention and are eligible to file their claims for economic control. The

Pentagon has also appeared slow to focus on the region. The U.S. Coast Guard

maintains just two working icebreakers, with another docked until repairs

are authorized. The question of expanding the icebreaker force has been left

unanswered, while a broader, interagency review of Arctic policy has

continued for nearly two years. A new national security policy directive is

nearing completion.

Still, the United States did begin continental-shelf mapping around Alaska

last year and this, turning up evidence that the U.S. continental shelf

claim may extend north of Alaska by at least 600 nautical miles. The CIA is

said to be analyzing Russian Arctic activities closely, and the National

Geospatial-Intelligence Agency has delivered to the Coast Guard a

sophisticated model of the Lomonosov Ridge and the High Arctic. The Coast

Guard set up a temporary base this past summer at Point Barrow, Alaska, and

tested operating in the Arctic. The service's commandant, Adm. Thad Allen,

emphasizes the need to prepare for handling oil-spill cleanups and

tourist-ship rescues and for policing ship traffic in remote seas. But the

resources are lacking. "There's water up there where there didn't use to be,

and I'm responsible for it," he says.

U.S. and other diplomats insist that the Arctic will not become a new Wild

North, where resource rivalries, backed by armed forces, play out. "No

nation has said they will take matters into their own hands," assures

Norwegian diplomat Karsten Klepsvik. The Arctic, too, has long had a

tradition of cross-national cooperation on science. A Russian icebreaker,

for instance, cleared a path for a Danish mapping voyage. Canadian and U.S.

ships and researchers teamed up last month to explore the very sea bottom

that might be disputed.

Those are certainly hopeful notes. But however it goes, Washington remains unready for the new age of the Arctic. "I believe it is a race," says Mead Treadwell, an Anchorage businessman who chairs the U.S. Arctic Research Commission, a federally appointed advisory group. "This is a time in human history when rules and practices for the Arctic will be set. If we ignore this opportunity, we may not be happy with the result." It is pretty clear, though, that ignoring the High North will not be an option.

Copyright © 2008 U.S. News & World Report, L.P. All rights reserved. To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.usnews.com