Earth's Most Prominent Rainfall Feature Creeping Northward

July 1, 2009

The rain band near the equator that determines the supply of freshwater to nearly a billion people throughout the tropics and subtropics has been creeping north for more than 300 years, probably because of a warmer world, according to research published in the July issue of Nature Geoscience.

If the band continues to migrate at just less than a mile (1.4 kilometers) a year, which is the average for all the years it has been moving north, then some Pacific islands near the equator — even those that currently enjoy abundant rainfall — may be drier within decades and starved of freshwater by midcentury or sooner. The prospect of additional warming because of greenhouse gases means that situation could happen even sooner.

The findings suggest "that increasing greenhouse gases could potentially shift the primary band of precipitation in the tropics with profound implications for the societies and economies that depend on it," the article says.

"We're talking about the most prominent rainfall feature on the planet, one that many people depend on as the source of their freshwater because there is no groundwater to speak of where they live," says Julian Sachs, associate professor of oceanography at the University of Washington and lead author of the paper. "In addition many other people who live in the tropics but farther afield from the Pacific could be affected because this band of rain shapes atmospheric circulation patterns throughout the world."

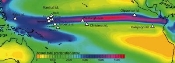

The band of rainfall happens at what is called the intertropical convergence zone. There, just north of the equator, trade winds from the northern and southern hemispheres collide at the same time heat pours into the atmosphere from the tropical sun. Rain clouds 30,000 feet thick in places proceed to dump as much as 13 feet (4 meters) of rain a year in some places. The band stretching across the Pacific is generally between 3 degrees and 10 degrees north of the equator depending on the time of year. It has recently been hypothesized that the intertropical convergence zone does not reside in the southern hemisphere for reasons having to do with the distribution of land masses and locations of major mountain ranges in the world, particularly the Andes mountains, that have not changed for millions of years.

The new article presents surprising evidence that the intertropical convergence zone hugged the equator some 3 ½ centuries ago during Earth's little ice age, which lasted from 1400 to 1850.

The authors analyzed the record of rainfall in lake and lagoon sediments from four Pacific islands at or near the equator.

One of the islands they studied, Washington Island, is about 5 degrees north of the equator. Today it is at the southern edge of the intertropical convergence zone and receives nearly 10 feet (2.9 meters) of rain a year. But cores reveal a very different Washington Island in the past: It was arid, especially during the little ice age.

Among other things, the scientists looked for evidence in sediment cores of salt-tolerant microbes. On Washington Island they found that evidence in 400- to 1,000-year-old sediment underlying what is now a freshwater lake. Such organisms could only have thrived if rainfall was much reduced from today's high levels on the island. Additional evidence for changes in rainfall were provided by ratios of hydrogen isotopes of material in the sediments that can only be explained by large changes in precipitation.

Sediment cores from Palau, which lies about 7 degrees north of the equator and in the heart of the modern convergence zone, also revealed arid conditions during the little ice age.

In contrast, the researchers present evidence that the Galapagos Islands, today an arid place on the equator in the Eastern Pacific, had a wet climate during the little ice age.

They write, "The observations of dry climates on Washington Island and Palau and a wet climate in the Galapagos between about 1420-1560/1640 provide strong evidence for an intertropical convergence zone located perennially south of Washington Island (5 degrees north) during that time and perhaps until the end of the eighteenth century."

If the zone at that time experienced seasonal variations of 7 degrees latitude, as it does today, then during some seasons it would have extended southward to at least the equator, Sachs says. This has been inferred previously from studies of the intertropical convergence zone on or near the continents, but the new data from the Pacific Ocean region is clearer because the feature is so easy to identify there.

The remarkable southward shift in the location of the intertropical convergence zone during the little ice age cannot be explained by changes in the distribution of continents and mountain ranges because they were in the same places in the little ice age as they are now. Instead, the co-authors point out that the Earth received less solar radiation during the little ice age, about 0.1 percent less than today, and speculate that may have caused the zone to hover closer to the equator until solar radiation picked back up.

"If the intertropical convergence zone was 550 kilometers, or 5 degrees, south of its present position as recently as 1630, it must have migrated north at an average rate of 1.4 kilometers — just less than a mile — a year," Sachs says. "Were that rate to continue, the intertropical convergence zone will be 126 kilometers — or more than 75 miles — north of its current position by the latter part of this century."

SOURCE: University of Washington