Published on September 4th, 2009

Only after I snoozed my way through high

school science class did science become more compelling than

science fiction.

Back then, there was just no compelling reason to pay attention.

Just a browzy fly buzzing in a smelly boring lab full of long

agreed-upon dull principles that were really neither here nor there.

In those days there were no colliding continents or hydrothermal

vents or extremophile lifeforms. We looked to sci-fi for that.

Who knew that our planet would soon be busting at the seams with

7 billion of us. That our fossil fuel use would threaten our

survival with climate changes — on a level unseen on the planet

since Cyanobacteria made it safe it for oxygen-breathers 4 billion

years ago.

Or that we would not only discover vast strange heat

sources under the ocean but that we’d actually consider

mining these hydrothermal vents for renewable energy:

That was the sort of story you’d only find in science fiction back

then.

But yet, here we are. This is not science fiction:

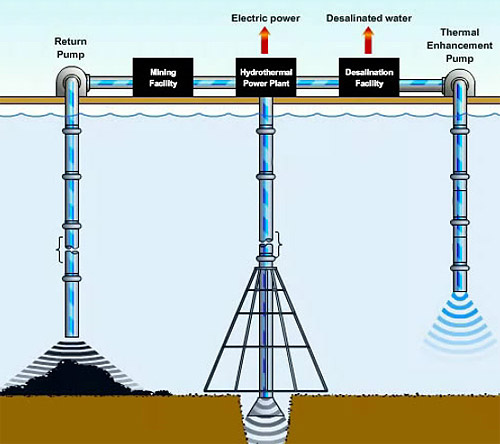

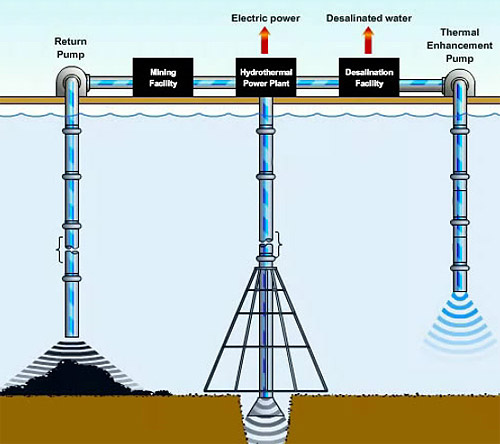

The

energy potential is staggering. In the Gigawatt range per vent.

The Marshall Hydrothermal Recovery System would use the heat from

hydrothermal vents 7,000 feet under the sea to make electricity. Its

temperature is incredibly high, 750 degrees Fahrenheit; hot enough

to melt lead, but it does not boil because of the intense pressures

at the depths where the vents are located.

Superheated fluid would be propelled up through a through a (well

insulated!) pipe to an oil platform located on the surface above the

vent. The superheated fluid is carried by means of flow velocity,

convection, conduction, and flash steam pressure as it rises and the

ambient pressure is decreased.

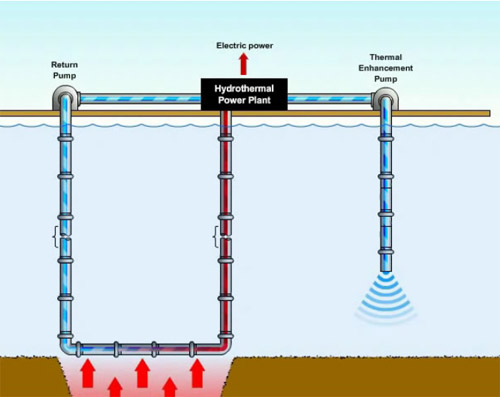

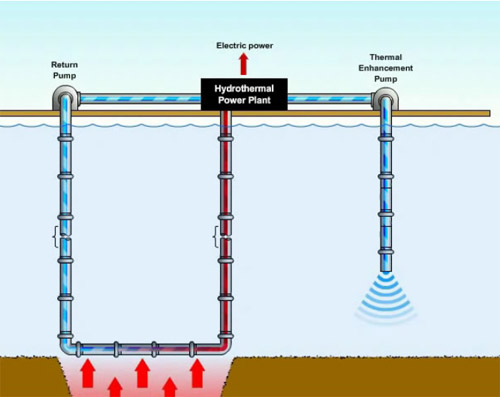

Once delivered to the platform, the heat energy contained in the

fluid can be extracted to generate electricity. Since the amount of

energy available from any thermal system is dependent on the

difference in temperature between two points, the system also

includes a Thermal Enhancement Pipe.

This is simply an open pipe, like a large drinking straw, which

extends down below the layer of relatively warm water on the surface

to the permanently frigid waters below. By withdrawing water from

that pipe and using it as the cold side of any heat reaction, much

more energy can be extracted from the process than could be

delivered without it.

But what about those extremophile lifeforms down there at

the vent? This has got to be ecologically disruptive!

Marshall Hydrothermal is pretty frank about the horrible

ecological consequences: The company says that there is no

way to sugar-coat the fact that these organisms will die so that we

humans can live our much more exciting lives though electricity.

The company “plans” to relocate the local flora and fauna to another

vent nearby. But can people work 7,000 feet down to carefully pull these

limpet-like creatures off the sides of volcanic vents? I’m not quite

sure how that would happen.

Or, perhaps a closed loop system would be safer?

Marshall offers this alternative method:

Closed Loop Version

This looks a little less invasive: a closed loop system.

Rather than bringing up the hydrothermal fluid itself with bits and

pieces of sea creatures as well, a simple heat exchange is effected

within a closed loop: all the fluid is contained in the pipe and heated

at the vent and circulated up for use to drive the turbines on the

surface.

The cooled fluid is then sent back to be reheated by the vent again

and again, but the hydrothermal fluid itself is never actually brought

to the surface. More than just a huge renewable energy supply is at

stake here.

We could also be making desalinated water from the ocean

vents:

At least 264 million gallons of fresh water daily.

20 million gallons of hot fluid would flash to steam at the surface

and that could be distilled back into fresh water. Further purification

would be needed, but the natural heat from the process itself provides

the most important part of the energy needed for the process. Fresh

water is the new oil.

If even only 50% of the total volume could be recovered, that would

still provide about 264 million gallons of fresh water daily.

Catch 22

Unfortunately, desalination apparently requires the (more

ecologically disruptive) open loop system, to work. (See first diagram)

But, if that could be solved, there is another argument for

mining the actual fluid (open loop); not just the heat (closed

loop) system.

The materials in these geologically ancient vent fluids include iron,

gold, silver, copper, zinc, cadmium, manganese, and sulfur. Halides,

sulphates, chromates, molybdates and tungstates are also abundant.

When the fluid is trapped, the slurry left over after

the heat is extracted can be loaded aboard ships for processing

elsewhere, or processed on-site.

Cap and Trade would also help fund this completely

new form of renewable energy extraction. Who better to carry it out than

the oil industry. They already have the expertize with ocean drilling

extraction.

Turns out there is also significant amounts of methane gas mixed into

the fluid. Maybe there is a way to cap that for remediation-cum-fossil

energy at the same time, as well as selling the renewable electricity,

fresh water and minerals produced by the vents.

For the oil industry, with all these inducements, surely switching to

mining renewable energy would be more cost effective

than having to keep on paying media outlets and school districts and

think-tanksfull of talking heads to keep enough people ignorant enough

about climate change to slow the legislation needed to stop it; decade

after decade.

Let’s hope.

Images from Flikr users

aakova and

thomitheos

Via

Marshall Hydrothermal

a Green Options

Media Production.

Some Rights

Reserved To subscribe or visit go to:

http://cleantechnica.com

|