Thomas Lee for The New York Times

This abandoned mine in Guyun Village in China exhausted the local

deposit of heavy rare-earth elements in three years.

Just one problem: These elements come almost entirely from China,

from some of the most environmentally damaging mines in the country,

in an industry dominated by criminal gangs.

Western capitals have suddenly grown worried over China’s near

monopoly, which gives it a potential stranglehold on technologies of

the future.

In Washington, Congress is fretting about the United States

military’s dependence on Chinese rare earths, and has just ordered a

study of potential alternatives.

Here in Guyun Village, a small community in southeastern China

fringed by lush bamboo groves and banana trees, the environmental

damage can be seen in the red-brown scars of barren clay that run

down narrow valleys and the dead lands below, where emerald rice

fields once grew.

Miners scrape off the topsoil and shovel golden-flecked clay into

dirt pits, using acids to extract the rare earths. The acids

ultimately wash into streams and rivers, destroying rice paddies and

fish farms and tainting water supplies.

On a recent rainy afternoon, Zeng Guohui, a 41-year-old laborer,

walked to an abandoned mine where he used to shovel ore, and pointed

out still-barren expanses of dirt and mud. The mine exhausted the

local deposit of heavy rare earths in three years, but a decade

after the mine closed, no one has tried to revive the downstream

rice fields.

Small mines producing heavy rare earths like dysprosium and terbium

still operate on nearby hills. “There are constant protests because

it damages the farmland — people are always demanding compensation,”

Mr. Zeng said.

“In many places, the mining is abused,” said Wang Caifeng, the top

rare-earths industry regulator at the Ministry of Industry and

Information Technology in China.

“This has caused great harm to the ecology and environment.”

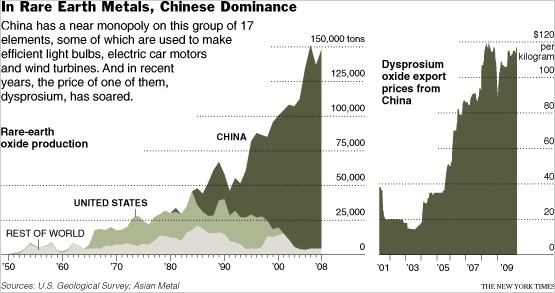

There are 17 rare-earth elements — some of which, despite the name,

are not particularly rare — but two heavy rare earths, dysprosium

and terbium, are in especially short supply, mainly because they

have emerged as the miracle ingredients of green energy products.

Tiny quantities of dysprosium can make magnets in electric motors

lighter by 90 percent, while terbium can help cut the electricity

usage of lights by 80 percent. Dysprosium prices have climbed nearly

sevenfold since 2003, to $53 a pound. Terbium prices quadrupled from

2003 to 2008, peaking at $407 a pound, before slumping in the global

economic crisis to $205 a pound.

China mines more than 99 percent of the world’s dysprosium and

terbium. Most of China’s production comes from about 200 mines here

in northern Guangdong and in neighboring Jiangxi Province.

China is also the world’s dominant producer of lighter rare earth

elements, valuable to a wide range of industries. But these are in

less short supply, and the mining is more regulated.

Half the heavy rare earth mines have licenses and the other half are

illegal, industry executives said. But even the legal mines, like

the one where Mr. Zeng worked, often pose environmental hazards.

A close-knit group of mainland Chinese gangs with a capacity for

murder dominates much of the mining and has ties to local officials,

said Stephen G. Vickers, the former head of criminal intelligence

for the Hong Kong police who is now the chief executive of

International Risk, a global security company.

Mr. Zeng defended the industry, saying that he had cousins who owned

rare-earth mines and were legitimate businessmen who paid

compensation to farmers.

The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology issued a draft

plan last April to halt all exports of heavy rare earths, partly on

environmental grounds and partly to force other countries to buy

manufactured products from China. When the plan was reported on

Sept. 1, Western governments and companies strongly objected and Ms.

Wang announced on Sept. 3 that China would not halt exports and

would revise its overall plan. But the ministry subsequently cut the

annual export quota for all rare earths by 12 percent, the fourth

steep cut in as many years.

Congress responded to the Chinese moves by ordering the Defense

Department to conduct a comprehensive review, by April 1, of the

American military’s dependence on imported rare earths for devices

like night-vision gear and rangefinders.

Western users of heavy rare earths say that they have no way of

figuring out what proportion of the minerals they buy from China

comes from responsibly operated mines. Licensed and illegal mines

alike sell to itinerant traders. They buy the valuable material with

sacks of cash, then sell it to processing centers in and around

Guangzhou that separate the rare earths from each other.

Companies that buy these rare earths, including a few in Japan and

the West, turn them into refined metal powders.

“I don’t know if part of that feed, internal in China, came from an

illegal mine and went in a legal separator,” said David Kennedy, the

president of Great Western Technologies in Troy, Mich., which

imports Chinese rare earths and turns them into powders that are

sold worldwide.

Smuggling is another issue. Mr. Kennedy said that he bought only

rare earths covered by Chinese export licenses. But up to half of

China’s exports of heavy rare earths leave the country illegally,

other industry executives said.

Zhang Peichen, deputy director of the government-backed Baotou Rare

Earth Research Institute, said that smugglers mix rare earths with

steel and then export the steel composites, making the smuggling

hard to detect. The process is eventually reversed, frequently in

Japan, and the rare earths are recovered. Chinese customs officials

have stepped up their scrutiny of steel exports to try to stop this

trick, one trader said.

According to the Baotou institute, heavy rare-earth deposits in the

hills here will be exhausted in 15 years. Companies want to expand

production outside China, but most rare-earth deposits, unlike those

in southern China, are accompanied by radioactive uranium and

thorium that complicate mining.

Multinational corporations are starting to review their dependence

on heavy rare earths. Toyota said that it bought auto parts that

include rare earths, but did not participate in the purchases of

materials by its suppliers. Osram, a large lighting manufacturer

that is part of Siemens of Germany, said it used the lowest feasible

amount of rare earths.

The biggest user of heavy rare earths in the years ahead could be

large wind turbines, which need much lighter magnets for the

five-ton generators at the top of ever-taller towers. Vestas, a

Danish company that has become the world’s biggest wind turbine

manufacturer, said that prototypes for its next generation used

dysprosium, and that the company was studying the sustainability of

the supply. Goldwind, the biggest Chinese turbine maker, has

switched from conventional magnets to rare-earth magnets.

Executives in the $1.3 billion rare-earths mining industry say that

less environmentally damaging mining is needed, given the importance

of their product for green energy technologies. Developers hope to

open mines in Canada, South Africa and Australia, but all are years

from large-scale production and will produce sizable quantities of

light rare earths. Their output of heavy rare earths will most

likely be snapped up to meet rising demand from the wind turbine

industry.

“This industry wants to save the world,” said Nicholas Curtis, the

executive chairman of the Lynas Corporation of Australia, in a

speech to an industry gathering in Hong Kong in late November. “We

can’t do it and leave a product that is glowing in the dark

somewhere else, killing people.”