Is the Environment to Blame for the Rise in Autism Cases?

Autism cases are on the rise. Or so the most recent data would have us believe. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that 1 in 100 children in the U.S. have been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) -- up from 1 in 150 in 2007. A study in the journal Pediatrics in October 2009 revealed similar numbers -- parents of 1 in 90 children reported that their child had ASD. With boys, the rate of ASD was 1 in 58. Without a doubt, autism is the country's fastest-growing developmental disability, affecting more children than cancer, diabetes and AIDS combined. Still, in dealing with a childhood disorder that ranges from "highly functioning" to uncommunicative, and such a long list of potential triggers and treatments, even the numbers themselves are subject to questioning.

"It irritates me to no end that we still argue over whether there is an increase in incidence," says Michael Merzenich, Ph.D., a neuroscientist at the University of California San Francisco who has pioneered research in brain plasticity (essentially, retraining brains) and leads the brain-training software company Posit Science. "I think there is lots of evidence for increased incidence," Merzenich says. "Overwhelmingly it supports that there are things in the environment that are contributing to the rate of incidence. But people still argue."

Doubters point out that autism is better understood today and more frequently diagnosed. Some have even suggested that an autism diagnosis may be a means to an end -- a way for parents to get the immediate speech and physical therapies their children need to prevent long-term delays. Massachusetts-based health writer Lisa Jo Rudy, mother to one autistic child, Tom, 13, as well as to a 10-year-old daughter, Sara, is one such skeptic. "Are we simply calling what used to be called being a ‘dweeb' autism?" Rudy asks. The National Institute of Mental Health writes: "It is unclear from the report in Pediatrics whether the 1 in 90 estimate is measuring a true increase in ASD cases or improvements in our ability to detect it."

Researchers like Merzenich say the waffling over numbers is beside the point -- too many children are living with the disorder, and not enough research is focusing on what's causing it or how best to treat it. The term "autistic" was not even part of the modern lexicon until it was introduced by Hans Asperger and Leo Kanner in the 1940s -- the word itself (containing the Greek autos) describes the self-absorption that is a hallmark of the disorder. While it takes many forms, autism affects social interaction and communication and leads to the development of intense habitual interests. Often, after a year of seemingly normal interaction, autistic kids will fail to respond to stimuli, make eye contact or turn at the sound of their name. They may not talk readily, or they may repeat themselves incessantly. They are likely to follow compulsive behavior, such as shaking their hands, stacking objects or repeating daily activities the exact same way each day. The treatment is years of intensive -- and expensive -- therapy.

Richard Lathe, Ph.D., a molecular biologist and former professor at the University of Strasburgh and Edinburgh University who wrote Autism, Brain, and Environment (Jessica Kingsley Publishers), calls the latest autism cases "new phase autism." Explaining the term, Lathe says, "The rate of autism was quite low between the 1940s and 1980s. The beginning of the 1980s saw a marked increase in the incidence and prevalence of autism. Rates have gone up at least tenfold. It indicates that it can't just be genetic -- it must be environmental."

The Chemical Connection

|

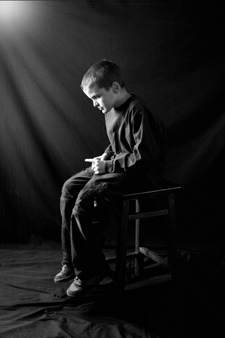

| Gavin Schultz has been steadily improving from autism since beginning biomedical treatments. |

| © c/o Cindy Schultz |

The debate over the connection between vaccinations -- particularly those preserved with mercury-containing thimerosal -- and autism has been widely publicized, and is still the subject of controversy. The connection makes sense, says Lathe, because "People who suffer from lead or mercury poisoning appear to be autistic." Thimerosal is still found in flu vaccines and the most recent H1N1 or "swine flu" vaccine, as well as a few single-dose vaccines. But vaccines are no longer the biggest mercury culprit, though aluminum, which is used as an adjuvant (an agent to stimulate the immune response) in many vaccines remains a concern.

James Adams, Ph.D., the head of the Autism/Asperger's Research Program at Arizona State University says, "The two major sources of mercury are from dental fillings and mercury from seafood...And that in turn comes from the environment, from coal-burning power plants and other sources [including waste incinerators]. It just happens to concentrate in large fish because they're pretty high in the food chain."

Cindy Schultz lives in Wisconsin not far from a coal-powered plant. She works with the nonprofit Autism Network through Guidance, Education & Life (ANGEL Inc.), which provides grants for autism treatments. Her oldest son has Asperger's syndrome, a milder form of autism; her younger son, Gavin, has a more severe form of autism. Her three daughters have not been affected. Still, Schultz believes that "the air is better than it was 40 years ago," and blames vaccinations -- not pollution -- for her sons' disorders.

One National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from the CDC that looked at mercury in the bloodstreams of women found that about 3% of women of childbearing age studied from 2003 to 2006 had at least 5.8 parts per billion (ppb) of mercury in their blood. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), meanwhile, "has determined that children born to women with blood concentrations of mercury above 5.8 parts per billion are at some increased risk of adverse health effects." And that's just one toxic chemical of concern. Others include air pollutants like lead and sulfur dioxide, water pollutants like arsenic and pharmaceuticals, and environmental toxins like phthalates (plasticizers), Bisphenol-A or BPA (used in some plastic water and baby bottles), and flame retardants known as polybrominated diphenyl ethers or PBDEs, which are used in everything from electronics equipment to plastics and furniture.

"The problem is these chemicals are everywhere," says Merzenich. "They've looked at levels of contamination from PBDEs in the polar regions and there are significant airborne levels everywhere. You really can't escape them." At the same time, he urges parents to avoid putting old plastic baby furniture, old mattresses and used electronic equipment in a baby's room, to keep potential PBDEs at bay.

In total, there are 3,000 chemicals that the EPA classifies as "high production volume." In other words, chemicals that the U.S. imports or produces at a rate of more than one million pounds per year. According to the EPA, 43% of these chemicals have not been tested for basic toxicity. In 2007, The Oakland Tribune arranged to test the body burden -- or level of chemicals -- in the blood of a Bay Area family that was attempting to live a chemical-free life. They found surprisingly high levels of PBDEs, particularly in the children. While the mother had 138 ppb and the father 102 ppb, their four-year-old daughter had 490 ppb and their 20-month-old son, 838 ppb. In the case of lab rats, at 300 ppb the rats exhibit behavioral changes.

"Our current situation is an incredibly backward position that everything is OK until there is an unequivocal scientific demonstration that it ain't safe," says Merzenich. "And really the only thing that protects us at all is the threat of lawsuits...The onus should be on the manufacturer and distributor of any new chemical to demonstrate that it's safe in terms that are acceptable to the public welfare. And certainly that includes that it's not going to impact the life or development of the fetal child."

The article continues at: http://www.alternet.org/story/145006/?page=3