It’s the 1970s All Over Again; A Strategy for Stagflation

By Christopher Ruddy

It seems like déjà vu: The 1970s are here again. Economic malaise, stubbornly high inflation, a polarized political environment — we even have Jimmy Carter again in the White House!

A Democratic friend of mine who would know tells me that, of all the former occupants of the White House, the one that President Barack Obama consults with and talks the most with by phone is none

other than the peanut farmer from Plains.

It shouldn’t be surprising. I remember the Carter years well. He didn’t have the same radical economic views that Obama holds, but they have the same attitude.

For instance, Carter blamed American business and the American people (remember his famous “malaise” speech?) for the nation’s economic woes. For Obama today, the wealthy and Wall Street are at

fault.

Both presidents have a cynical view of America’s role in world affairs, one that puts the onus of what’s wrong in the world on the United States and has us in a permanent state of hand-wringing as we

deal with friends and adversaries. Both presidents want the United States to distance itself from Israel.

The Carter years popped back on my radar screen recently when I watched a speech on C-Span given by author and historian Brian Domitrovic, who recently published Econoclasts: The Rebels Who Sparked the Supply-Side Revolution and Restored American Prosperity.

What was fascinating about Domitrovic’s talk was not so much his discussion of what the supply-siders did when President Ronald Reagan came to power — famously slashing income tax rates through the

Kemp-Roth Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 — but the economic milieu that gave rise to Reagan and the supply-siders.

Domitrovic argues that the 1970s were an incubator for an economic disease that led to a downturn lasting roughly 13 years, beginning in 1969 and encompassing several major, successive recessions.

Interestingly, liberal economist Paul Krugman recently wrote that the United States is entering a third Great Depression. Krugman believes that the original, 1930s Great Depression was followed not by normal, occasional recessions but truly a second depression — the decade of the 1970s.

Domitrovic seems to agree. “Our crisis today has not really proven historic. It is only the worst economic crisis of the last four, not the last eight, decades,” Domitrovic said in a recent speech to the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, sponsored in part by the Templeton Foundation.

“Except for the 1930s themselves, there was no mess like it stretching back over the centuries.

The 1970s were the second-worst period in all of American economic history,” he said.

Inflation Wipes Out Savers

How bad? Well, Domitrovic goes on to explain, there were no less than six recessions from 1969 to 1982 — that is, three back-to-back double-dips.

The U.S. government exited the ’60s with massive deficit spending as we tried to pay for the Vietnam War and Johnson’s Great Society programs. Republicans like President Richard Nixon continued

to spend and spend.

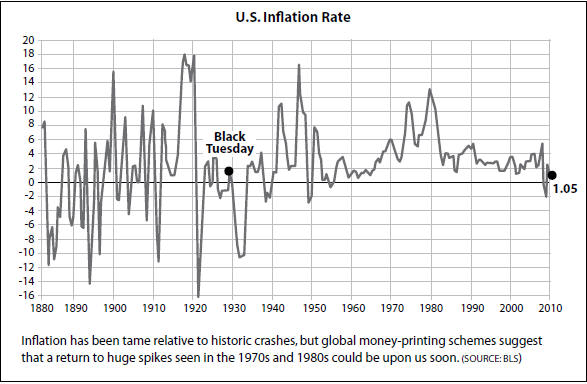

Soon, this led to inflation, which ran at about 9 percent during this period.

Savings were wiped out. No bank could offer savings rates high enough to matter, so most people simply spent, making matters worse.

None but the most established companies could offer bonds that paid enough to investors, so venture capital “hid out” in commodities instead, Domitrovic said in the talk. Jobs, predictably, disappeared, since new companies generate 20 times the jobs of older firms.

Even if stocks made the traditional 10 percent return, inflation nearly erased it, then a 50 percent capital-gains tax took whatever was left. “In the 1970s, stocks had to return 20 percent per annum to return any gain at all,”

Domitrovic said. “In real terms, the indexes lost ground. They lost more than even in the 1930s.”

Some investors tried to buy land, but property values went up with inflation and property taxes rose right along with it. The only real alternatives were hard commodities such as gold and, perhaps, paintings by Dutch masters.

“Saving money became a fine art in the 1970s, something closed to the masses. So the masses spent. Not spending meant watching your savings evaporate,” Domitrovic said.

For a while, the government even tried wage and price controls under Nixon. The gold standard was jettisoned permanently. Soon, an informal, institutionalized form of inflation came into play with COLAs — union-negotiated cost-of-living adjustments, perks that worked for some.

Growth faltered badly, and the vaunted post- World War II prosperity of 3.3 percent annual growth fell nearly in half to 1.8 percent, Domitrovic explained. Thus began the era of “stagflation,” a flat economy amid rising prices. Oil skyrocketed. Remember the infamous gas lines?

“According to Keynesian theory, this was a statistical impossibility, a freak, a contradiction in terms, yet it was an all-too-lived reality in the long 1970s,” Domitrovic said.

‘Stagflation’ Kicks in Hard

It has long been presumed in economic theory that, during periods of recession, the economy contracts, consumer spending takes a nose dive, and prices fall. As they do, commodities go into oversupply and also fall in price.

But that didn’t happen in the 1970s. An inflationary recession took place, commodity prices actually increased, and stagflation was born.

We are seeing a similar phenomenon today. While full-on inflation has not yet hit us — although we

believe it will — commodity prices have stayed aloft. Oil, the world’s most vital commodity, remains

stubbornly high for a recession.

It is true that oil has fallen from its record trading high of $147 a barrel in mid-July 2008. But today crude oil sells for $75 a barrel, still high in our book considering the price per barrel in 2004 was under

$30. A few years before that, crude sold for less than $15 a barrel.

Other commodities, despite a global recession, are quite high compared with their historical trends, including cotton, sugar, corn, rice, and metals.

There are two significant reasons that commodity prices remain high. First, economic meddling by Western countries and China, pumping trillions in stimulus, did not allow the economic cycle to

follow its natural course, which would have meant even lower consumer demand. Relative to the size

of its economy, China’s stimulus dwarfed the U.S. stimulus program: Beijing pumped in $586 billion

to help spike its domestic economy as U.S. and European demand for its products fell.

At first blush, the stimulus worked, staving off a deep recession. But in the long run it may have done more harm. Oil and other key commodities remain in high demand in China and other economies. Had oil prices fallen dramatically, as they would have without such intervention, the pump price for gasoline would have fallen to half of what it is today. This is turn would have freed up cash for American families and helped to lay the groundwork for a real, sustainable recovery.

The second reason commodity prices such as oil and gold remain high is the belief that inflation is building, growing inexorably into an unavoidable tsunami. “Quantitative easing,” the mass printing of paper money, has been under way at almost every major central bank in the world.

Sooner or later, this cash will find its way into our hands, what economists call “velocity.” It has to so

that we can pay down our staggering debt load, and that will trigger the inevitable monetary devaluation.

At FIR we have encouraged readers repeatedly to get Milton Friedman’s classic book Money Mischief:

Episodes in Monetary History, which elegantly illustrates the inflation phenomenon. As Friedman explained, inflation is often quite insidious. It has a long “lag effect,” the time between when banks increase the money supply and the eventual impact that new money has on consumer prices.

Policy Risks Are High

Just as we are seeing missteps among fiscal and monetary policymakers today, we saw the same in

the 1970s.

During the ’70s, policy responses to stagflation bordered on the comic, if you can take the long view and forget the real pain that people went through. Nixon, for instance, wanted high inflation. He thought it would create jobs. He could control prices later, he thought. Obama clearly embraces this view; Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke continues to keep the money spigots wide open.

President Gerald Ford later revised the policy, telling Americans to simply stop buying things. Carter compounded the error, figuring our consumption rate was a mass psychological disorder. If American consumers could just get therapy, Carter reasoned, we might snap out of it and consume less.

Even some of the brightest minds in economics of the time threw their hands up, essentially admitting that they, at least, could imagine no answer to the conundrum of stagflation. Nobel Prize winners said forget it, there’s no solution.

Yet a small band of economists, starting in the early 1960s with Robert Mundell, then Art Laffer and the journalist Jude Wanniski, started to promote a policy that later became inextricably linked to Reagan, even though Reagan himself was slow to adopt it — supply-side economics.

Mundell believed that the reason why we have economic crises in modern times relates directly to the misuse of two institutions, the Federal Reserve and the federal tax code, Domitrovic explained.

Mundell, then a young man working at the International Monetary Fund, said as much to President John F. Kennedy, who decided to ignore the Keynesians all around him and cut taxes while tightening the money supply.

The result, Domitrovic said, starting in the early 1960s, was growth of 4.5 percent and falling

inflation.

Looking back, nothing seemed to work for the economy in the 1970s until Federal Reserve

Chairman Paul Volcker took a page from Mundell, raising interest rates sky high.

In fact, the most important element in the inflation battle turned out to be Volcker, who

clamped down hard on the money supply to tame a wild bout of inflation.

As short-term rates rose, consumer spending and business borrowing slowed abruptly and the

economy fell into a deep, if salutary, recession.

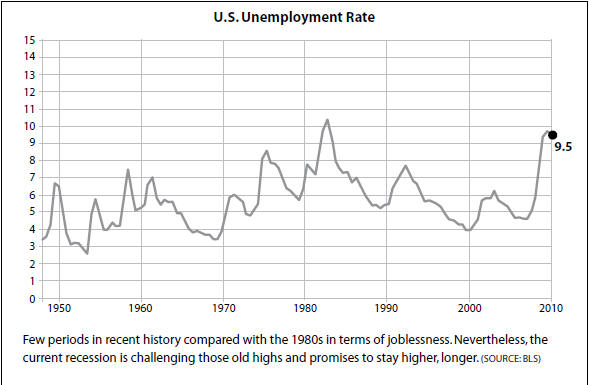

Before inflation was completely vanquished, however, the unemployment rate soared to over

10 percent by the fall of 1982. To capture the dual impact of rising inflation and unemployment,

economists came up with a term called the “misery index,” which combined the two figures.

Over the past several years, we have faced several of the same circumstances that led to the tumultuous period of the 1970s.

For example, we are now deeply involved in unpopular wars, there is rising conflict in the Middle East, and a loose monetary policy reigns at the Federal Reserve. Rates have been at virtually zero since the crisis began.

However, there are some important differences. For example, the influence of unions is much less

than it used to be. The economy is more energy efficient. Interest rates are substantially lower than

during the 1970s — for now. And the U.S. economy is far more susceptible to global pressures and

interference. Witness the effect China has had.

Another Lost Decade

As a result of the recent recession and an excessive debt buildup over the past several decades,

the economy is likely to go through a multi-year de-leveraging cycle. This means less risk-taking,

a slowdown in consumer spending, and slower economic growth.

The Federal Reserve recently admitted this, warning that it would take another five or six years for the United States to recover fully and that unemployment would exceed 7 percent for the remainder of Obama’s first term.

Yet the past might repeat itself, meaning we could see rising inflation and higher interest rates combined with weak employment and flat stock prices. Such a scenario cannot be ruled out, especially considering the risk of policy mistakes in Washington.

There is a way out: tax cuts. But it is clear that President Obama and the Democrats in Congress are ideologically hostage to the view that tax cuts are evil.

Not only has Obama been pushing new taxes but also he soon will preside over one of the largest

tax increases in history. If he and Congress do absolutely nothing, the George W. Bush tax cuts

expire at the end of this year. Americans for Tax Reform estimates that this will yield more than $1

trillion in tax increases.

Taxes on every income bracket will rise by more than 10 percent. The tax on dividends — a common

source of income for retirees — will leap to 39.6 percent from the current 15 percent.

The capital-gains tax will jump by a third — to a 20 percent rate from its current 15 percent. The

estate tax comes back in 2011 and could return even sooner as Congress looks around for quick cash to

begin paying down our $1.47 trillion debt.

The Obama healthcare law includes an additional 3.8 percent tax on interest, dividends, and capital

gains on upper-bracket taxpayers, beginning in 2013.

Of course, healthcare expenses, too, will almost certainly rise as Obamacare kicks in over the next

few years. That hits everyone.

The United States has generated three consecutive quarters of positive GDP growth. Yet the possibility

of a double-dip recession remains strong.

We could fall into a combination of rising inflation, high taxes, and low growth for years on

end. That would spark a series of double-dips in the economy, recreating the 1970s period.

Tactical Investing Is Key

Supply-siders today would say that there are two things the government could do to get the economy

going again: cut taxes, and for the Federal Reserve to maintain a constant money supply.

Together, declining inflation (thanks to Volcker) combined with lower taxes (thanks to Reagan)

finally did the trick in the 1980s and helped the stock market break out of a decade-long trading

range.

Even Bernanke has joined the chorus of those seeking preservation of the Bush tax cuts, giving

support to a small band of conservative Democrats in the face of stiff opposition from the Obama

political team and the Democratic leadership.

With equity markets now back at 1998 levels following one of the most challenging decades since

the Great Depression, what should you do right now?

Astute investors need to embrace the current market period and understand what actually drives

stock market prices. Over the next several years, investors face the threat of higher taxes, increased

regulation, rising interest rates, and the potential for another period of substantially higher inflation.

There is some hope that big Republican gains in November could turn things around and force

Obama to renew the Bush tax cuts and to even cut other taxes. So far Obama is giving indications that

he’s open to compromise.

Yet, unlike in the 1980s and 1990s, today’s scenario will not be a buy-and-hold market in which

you can invest in an index fund and forget about it for several years.

Instead, it appears that tactical investing or absolute return funds may be a more useful strategy

to help navigate what is likely to be fairly challenging investment environment.

When considering your strategy, here are some major points to keep in mind:

• Cash won’t be king. During periods of inflation it’s better to own assets, even stocks, over cash,

which will lose value.

• Think globally. Investments in emerging countries, especially blue-chip dividend payers with

emerging-market income sources, are a smart way to diversify.

• Real estate. Real estate prices are low now but will rise with inflation. Pick key areas in the United

States with good state and local tax regimes where baby boomers will retire. Be a long-term investor

when it comes to real estate.

• Be consistent. If you like dividend stocks, continue to reinvest the dividends, even during a

down market.

• Avoid the bond market, especially government bonds.

• Use some leverage on your brokerage accounts.

Some brokerage houses are charging between 1 and 2 percent for margin loans. If you had a dividend

stock paying 5 percent and invested half of that return in another dividend stock paying 5 percent,

your overall return would be more than 7 percent.

The Fed has stated repeatedly that it will keep rates low for a long time, so now is the time to juice your

income investments.

Copyright © 2010 Financial Intelligence Report.