Who pays for pollution?

Cities spend millions to keep farm chemicals out of drinking water

THE COLUMBUS DISPATCH

The system Columbus water officials use to measure atrazine levels begins with an old, battered plastic bottle wrapped in duct tape and tied to a rope.

Every two weeks, a utilities worker lowers the bottle in 11 spots in streams that run past farms on their way to the city's three main reservoirs. The worker labels the water samples with the date and location and returns them to the city's lab.

It's part of a warning system to measure how much atrazine and other farm pollutants are washed off fields and into Columbus' main sources for drinking water. They also check for six other farm herbicides - two more than the feds suggest -frequently found in water: acetochlor, alachlor, cyanazine, metolachlor, metribuzin and simazine.

Knowing how much is in the water helps officials estimate how much powdered carbon they will need to filter atrazine down to levels the federal government considers safe. The city has a separate program that pays farmers to reduce chemical use and runoff.

Heavy storms during planting season usually are a bad sign.

Columbus uses more than 10 tons of powdered carbon a day, costing taxpayers about $10,800 each day during spring and summer months when atrazine levels rise. The city spent more than $1.5million for the carbon and the tests in 2009.

"Over the years, we've gained a pretty good feel for when these events occur and what to look for," said Rick Westerfield, the city's Water Division administrator.

Federal regulations that date to 1992 require Columbus to look for atrazine in treated drinking water once every three months and once every month in the summer. Other cities are required to look more often or less often for the same contaminants, depending on levels detected by previous water tests.

There are no requirements to test the untreated water in streams or reservoirs.

Columbus utilities officials say the tests and a program that pays farmers to reduce runoff or switch to other herbicides helped reduce atrazine in reservoir water, particularly in Hoover Reservoir northeast of the city.

Hoover, the city's largest reservoir, is the most vulnerable to atrazine. Because the reservoir draws water from a relatively small, 200-square-mile agricultural area, the chemical builds up in the water and requires more filtering, said Matt Steele, Columbus' water-quality-assurance manager.

"We would see levels of 3parts per billion to 5 parts per billion," Steele said of tests in the 1980s. "When a level of that magnitude gets into that reservoir, we have to put up with it for about six months until other rains dilute it out."

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency sets an annual safe level for atrazine in drinking water at an average of 3 parts per billion. Steel said the city tries to limit it to no more than 2.5parts per billion at any time.

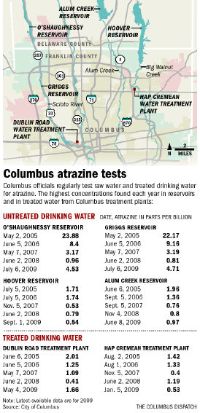

Over the past five years, tests have found atrazine in Hoover at concentrations no higher than 1.74 parts per billion, a level recorded on July 5, 2006.

Tests at Griggs and O'Shaughnessy reservoirs revealed higher concentrations, but Steele said atrazine doesn't linger as long there and that less filtering is required. Atrazine doesn't have a chance to build in Griggs and O'Shaughnessy because they are smaller than Hoover and the city's Dublin Road treatment plant drains them faster than the city's Hap Cremean plant drains Hoover.

Columbus paid about $225,000 to the Delaware County Soil and Water District from 2002 through 2004 to pay farmers who either agreed to cut runoff or stop using atrazine altogether.

"We saw it as the best way to get atrazine down (at Hoover) and keep it down," said Ed Miller, the district's watershed coordinator.

One of the first farmers to sign up was E.J. Miller of Galena. Miller is now retired, and his nephews grow corn and soybeans on the 600 acres he owns in Delaware County.

"Most people who farm solely in the (Hoover) watershed saw it as a chance to benefit the public a little without getting hit in the pocketbook real hard," Miller said of the program. "It just seemed like the right thing to do for a lot of folks."

Miller and Larry Ufferman, the soil and water district's administrator, said farmers likely haven't changed how much water runs off their land but are using more Roundup, another popular herbicide that isn't tested for in drinking water.

The weather has helped, too, E.J.Miller said.

"The atrazine level in the reservoir has been way low because we haven't had the (rain) events that cause it to be way high."

©2010, The Columbus Dispatch To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.dispatch.com