Abu Dhabi: Rise of a Renewable Energy Titan?

Oil rich Abu Dhabi sees renewable energy as the theme for the next chapter of its place in history. But writing that chapter has proven a lot tougher than its leaders initially anticipated.

Abu Dhabi -- United Arab Emirates It's no secret that oil rich Abu Dhabi sees renewable energy as the theme for the next chapter of its place in history. The emirate already has invested billions of dollars to pave the way to this new economy. It has taken stakes in many wind and solar power energy projects, started its own solar panel manufacturing business and put money in other solar panel manufacturers in Europe, United States and Asia. It also has formed partnerships with multinational energy, automotive and information technology giants and begun building a city from scratch to showcase low-carbon technologies.

Its foray into this new venture has just started, and already its leaders are discovering that making the transition from a fossil-fuel based economy isn’t easy, given the resources they are pursuing aren’t simply buried underneath their soil.

Four years after Abu Dhabi started down this path, its officials have had to redraw their master plan for the brand new Masdar City, whose build out has been significantly delayed. They have scrapped a plan to build a solar panel factory in Abu Dhabi. They also raised a second venture capital fund and saw opportunities in countries with clearer national renewable energy policy, such as China.

Abu Dhabi’s ambition has received at least good publicity if not admiration from political leaders and companies that see good business opportunities. It also has no shortage of skeptics who question whether the emirate is setting unrealistic goals and lacks the ability to reach them.

Emirate officials they have modified their ambitions to reflect the lessons they’ve learned. These changes will still enable them to reach their broader goals of becoming a cleantech hub and a seller of renewable energy.

“It’s not fair to say what was decided in 2006 will be held forever,” said Dale Rollins, chief operating officer of Masdar, the company created to oversee Abu Dhabi’s transition into renewable energy.

“Given the technology and market, the (initial plan) seemed like a good idea. The technology has moved on and the market has moved on. We say we can do it better and we can do it in less expensive ways,” said Rollins at a press conference at the World Future Energy Summit hosted by the Abu Dhabi government last week.

Taking On a New Role

Abu Dhabi, which is one of the seven emirates and the richest in oil reserves, publicly announced its foray into renewable energy and cleantech in general in 2006. It called the big plan the Masdar Initiative. The company to oversee the effort, Masdar, is made up of five businesses that include a power company, Masdar City, a research institute, an investment company and a business to develop carbon capture and sequestration projects.

The emirate has taken stakes in a series of renewable energy generation projects abroad, including the London Array offshore wind project in the United Kingdom, solar thermal power plants in Spain, and others in places such as Egypt and the Seychelles. Its first $250 million cleantech venture capital fund put money mostly in American companies, such as Solyndra and HeliVolt. Masdar and its partners have spent the fund and saw two exits for its portfolio companies: an initial public offering of HaloSource (water purifying and anti-microbial coating) and the sale of SiC Processing (recycling waste materials from silicon wafer manufacturing).

It raised a second, $290 million fund by early 2010, and plans to seek more investment opportunities in Asia. The fund has put $25 million into Chinese wind power developer, UPC Renewables China.

In 2008, Masdar announced it would inject $600 million to start Masdar PV and build a factory in Germany and then one in Abu Dhabi to make amorphous silicon thin films. Masdar planned to eventually put in roughly $2 billion to create a thin film manufacturing empire.

Masdar PV has struggled to grow in a global market that is dominated by companies with far larger fleets of factories. Masdar PV bought production equipment from Applied Materials, which decided to stop selling them last year. The seemingly sudden departure of not only its chief executive but also the chief operating officer last May raised questions about the health of its operation. Last September, Masdar PV said its solar panels could achieve 7.4 percent efficiency, which falls far behind other types of thin film panels (more than 10 percent) as well as the market-dominating crystalline silicon panels (typically around 16 percent).

Masdar PV, which built its first factory in Germany, had planned to build a factory in Abu Dhabi to supply panels to the Middle East. Company CEO Frank Wouters told Abu Dhabi’s newspaper, The National, earlier this month that they had abandoned the plan to build a factory in Abu Dhabi because of a lack of local demand for its product.

Abu Dhabi also is developing renewable energy projects on its home turf, where demand for energy is rising. Construction of a $600 million, 100-MW solar thermal power plant in Abu Dhabi began in the third quarter of last year and is set for completion in late 2012. The plant will use technology from Abengoa Solar, which uses parabolic mirrors to concentrate the sunlight onto fluid-filled tubes to produce steam, which then drives turbines to produce electricity.

The project, called Sham 1, is the first full-scale renewable energy plant for the emirate, said Mohamed Al Zaabi, general manager of Sham 1, during an interview. There is a 10-MW photovoltaic project built in 2009, but that was more of an effort to see how solar panels would fare in the hot and dusty desert environment. Masdar is planning to solicit bids for the 100-MW photovoltaic project, to be located in Abu Dhabi, later this year, Al Zaabi said.

Financing for Sham 1 is set to close in March this year, Al Zaabi said. Masdar is negotiating with 10 banks, most of them in Europe, to get the funds, added Al Zaabi, who declined to disclose their names.

Abu Dhabi wants 7 percent of its electricity supply to come from renewable sources by 2020, and most of that will come from solar. The plan is to install 1,500 MW of centralized and distributed solar energy generation by then, Al Zaabi said.

The emirate is developing a 30-MW wind energy project at home, but wind won’t play a key source as it had initially anticipated. It also looked into geothermal energy and drilled two, 2.5-kilometer test wells. The results showed its underground reservoirs aren’t hot enough to generate the steam necessary for driving turbines. But the resource could be enough to run heat exchangers to run air conditioning and pipe the cold air throughout homes and offices in a district-wide network, said Afshin Afshari, head of energy management for Masdar City, during a media’s tour of Masdar City grounds.

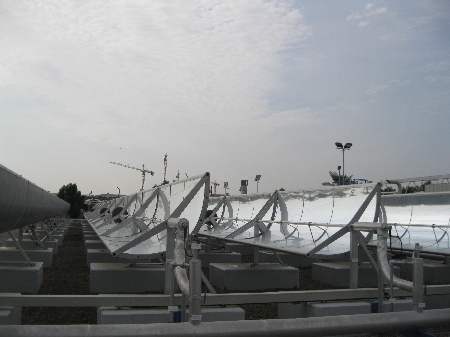

Cooling technologies are hot in the emirate, which faces summer temperatures around 47 degrees Celsius (118 degrees Fahrenheit). A pilot project that started last summer has been testing two methods of generating thermal energy to cool buildings. Engineered by Masdar City folks, the project uses two sets of mirrors to heat water to 180 degrees Celsius and send it to a double-effect absorption chiller to generate cool air for an office building on Masdar City site. One set of mirrors are Sopogy’s metal parabolic trough collectors. Mirroxx provided the second set, which are linear Fresnel collectors.

Re-Architecting the Cleantech Metropolis

The planning and construction of Masdar City is perhaps the most high-profiled undertaking by Abu Dhabi. Its planners originally pegged its cost at $22 billion and hoped to complete it by 2016 (construction started in 2008). They had imagined a city powered only by renewable energy generated within city limits and a network of mass transit. People would park their cars in garages at the city’s perimeter and walk or ride the public transport.

Abu Dhabi leaders want to use Masdar City to attract international investments. The city would house hundreds of companies, a research institute and 40,000 residents, as well as accommodating 50,000 commuters. Abu Dhabi has set aside about 6 square kilometers near its international airport for the city.

In short, Masdar City will be carbon neutral, city planners said.

City planners have changed the master plan significantly since 2006. The revised plan, announced last year and partly driven by the global economic downturn, no longer counts onsite generation as the only source of power. One of the original ideas was to paper the commercial and residential rooftops with solar panels. But doing so is more expensive than building a centralized solar power plant, Ahmed Baghoum, associate director of Masdar City, told me. Locating centralized power plants within the city isn’t critical, apparently, because Masdar City isn’t meant to be self-contained by operating its own electric grid. Instead, electricity generated within the city will feed into the national electric grid anyway.

Abu Dhabi’s goal to get 7 percent of electricity from renewable sources by 2020 also forced changes in the city’s power generation plan. Political leaders set the goal a few years after they started planning for Masdar City, and that prompted an emirate-wide evaluation at where to locate renewable power plants.

The 10-MW photovoltaic plant that came online sits on Masdar City land, and is supplying electricity for use at construction sites within the city and the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology, a campus that opened last September and became the first set of permanent buildings to rise from within the city boundaries. The institute, which is undergoing expansion, features 1 MW of solar panels on its roofs. That system will provide 30-35 percent of the institute’s current needs.

The institute is tasked with developing clean technologies for use within the city and for selling them in the global market. In fact, Masdar officials see the city as a test bed for new technologies.

“Masdar City is the glue that integrates the R&D, energy production, and commercialization efforts; it’s where everything gets tested and deployed,” Baghoum said.

The institute already is doing that. The graduate school, which includes student housing, is outfitted with sensors and software to monitor and measure its energy consumption frequently, including electricity and water, and to restrict the use of air conditioning. School officials will know if they and students don’t meet the goal of using at least 50 percent less energy than comparable buildings in rest of Abu Dhabi. And they will have to do modify their behavior to meet the goal. This type of demand-response system is being reviewed and tested in parts of the United States.

Another significant change to the master plan involves public transit. City planners initially were enamored with what’s called “Personal Rapid Transit,” which would be a network of driverless electric pods that move along tracks of magnets embedded in the ground. They put in a pilot route at the institute that shuttles campus denizens and visitors for 800 meters between a parking lot and the school.

The plan was to build PRT network would run under an elevated street level. Instead of digging an underground network, the PRT would run above ground. On top of the PRT network would be a platform built throughout the city to render them the street level for pedestrians to move about.

The idea to re-define the street levels came because of the high water table and the salty ground water in the region, said Inaki Azaldegui, development manager for Masdar City. You can hit the water table at 1 meter below ground, and the water’s high salinity is a corrosive force to reckon with, he added.

But building a new street level citywide is expensive, and so is the PRT network. The emergence of electric vehicles also made Masdar officials wonder whether electric rides, which are far less polluting than gasoline cars, might not be an equally clean if not a more convenient means of transportation within the city. Would Masdar residents and office workers want to walk after they’ve gone shopping and need to carry bags of goods?

Electric taxis might end up plying the streets, Azaldegui said.

“Initially we were thinking more vertical for the pedestrians, transportation and utility. Now we rather have pedestrians and vehicles on the same level,” Baghoum said. “We are looking at convenience for the residents and visitors.”

The idea of running a light rail service remains intact. The rail service also will connect Masdar to other communities.

The overhaul of the master plan will allow the government to save about 15 percent of the original $22 billion cost estimate, Baghoum said. The government has already invested a few “billions of dollars” into developing the new city so far, said Dale Rollins, chief operating officer of Masdar.

The new plan also sets new deadlines. Instead of completing the entire Masdar City by 2016, which seemed overly ambitious to begin with, city officials plan to build the first phase by 2015 and complete the entire project no earlier than 2020 (and possibly by 2025).

Phase 1 will build out the Masdar Institute and add office and residential communities. Siemens, which will provide building energy management and power grid products to Masdar City, has reserved an office complex next to the institute, Azaldegui said. Headquarters for Masdar the company and the International Renewable Energy Agency also will materialize. A “Swiss Village” for companies from Switzerland, as well as a complex for South Korean companies might start to take shape during phase 1, he added. This first phase will accommodate 7,000 residents and 12,000 commuters, Baghoum said.

Whether the carbon-neutral city will materialize as planned of course remains to be seen. Abu Dhabi leaders appear committed to spending the money and moving ahead with plans not just involving the new city but also investments in renewable energy technologies and generation worldwide. And what drives them is the recognition that their fossil fuel reserves won’t last forever.

Bader Al Lamki, a senior project manager of Masdar working on carbon capture and sequestration projects sees Masdar as a place for future generations. “We want to be a major energy supplier for decades to come,” he said.

Disclosure: The Abu Dhabi government paid for my travel and lodging for the 2011 Future World Energy Summit.

To subscribe or visit go to:

http://www.renewableenergyaccess.com

To subscribe or visit go to:

http://www.renewableenergyaccess.com