Plutonium-laced fuel heightens Japan's nuke woes

R. Colin Johnson

3/14/2011 8:05 PM EDT

The devastating 9.0 earthquake that rocked northern Japan and the ensuing tsunami have already claimed an estimated 10,000 victims. But the worst may be yet to come. Experts estimated that the next 48 hours will be crucial in determining whether Japan's nuclear disaster unfolds like the U.S. Three Mile Island accident in 1979 or like the meltdown at Russia's Chernobyl plant in 1986.

Two dozen Japanese workers at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station along with17 U.S. crew members of the USS Ronald Reagan have already been decontaminated for radiation exposure. If offshore winds shift, as predicted by Japanese weather forecasters, then airborne radioactive clouds could be headed for the Japanese mainland in the next 24 hours.

Observers said the biggest threat is plutonium fuel. Only one Fukushima reactor uses plutonium-enriched uranium fuel known as MOX, or "mixed oxide" fuel. A hydrogen explosion at the No. 3 reactor on Sunday (March 13) injured 11 workers. So far, Japanese officials said the containment vessel in the No. 3 reactor appears to be holding. But it could take weeks or even months before the MOX fuel cools to levels that no longer threaten public safety.

"If there is a large-scale release of plutonium into the air this could become the worst nuclear disaster in history," predicted Ira Helfand, a member of the board of Physicians for Social Responsibility. "So far, the venting of radioactive steam has been blown out to sea, but tomorrow [March 15] the wind is forecast to shift to northeast which means any radiation released tomorrow will be blown straight toward Tokyo, which is less than 150 miles away."

A release of deadly plutonium would require heightened precautions to protect Japanese citizens, particularly if winds shift. Helfand said these would include staying indoors and testing water and foods supplies. "Most of the exposure to people at Chernobyl, for instance, was from children drinking contaminated milk that had not been tested," Helfand said, resulting in high rates of thyroid cancer in children.

Third explosion

Making matters worse, a third explosion, this one inside Fukushima's No. 2 reactor, was reported Tuesday morning Japan time. Tokyo Electric Power Co. confirmed that radiation from the blast likely leaked after the No. 2 reactor's containment vessel was damaged, Kyodo news service reported.

Despite safety concerns that have prompted the use of backup systems like buried diesel fuel tanks for secondary generators at U.S. nuclear plants, experts are baffled at the lack of adequate backup systems in Japan. The lack of functioning secondary generators, for example, has led directly to cooling problems linked to the three explosions at Fukushima.

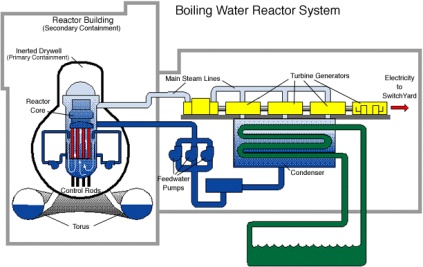

Those aging boiling-water reactors were designed by General Electric. The inner reactor core--which generates heat using nuclear fission in a controlled chain reaction--boils circulating water which in turn drives a steam turbine to generate electricity. The heated water is then circulated through cooling pipes which, like a car radiator, cool the water before it re-enters the reactor.

When the earthquake struck last Friday about 80 miles off the coast of Sendai, Japan's nuclear reactors automatically shut down. Control rods were then inserted to dampen the fuel rods and stop the reactor's chain reaction. Electric pumps were supposed to continue running to circulate the hot water through cooling pipes, allowing the reactors to go into an orderly shut-down mode.

Then the power grid went down. Backup generators kicked on when the quake struck to keep cooling water circulating.

Then the tsunami hit.

How the fail safe measures failed

"Backup power initially worked, but failed when the sea wall protecting the site was found to be no where near high enough to stop the tsunami from flooding the generators," said Mary Olson, a nuclear waste specialist at the Nuclear Information and Resource Service. "Of course, the generators should not have been placed in low-lying areas behind the sea wall--that was clearly a human error."

Once the emergency generators were knocked out, eight sets of backup batteries were brought online to keep the pumps going. Initially that worked too, but after about eight hours and hundreds of damaging aftershocks, their power was exhausted and plant operators began loosing control of the rising temperature inside the containment vessels.

"For every single nuclear reactor in the world, 50 percent of the risk comes from loss of power to the site. Reactors do not power themselves, but depend on external sources of electricity for their control rooms, pumps and other auxiliary equipment," said Olson. "A nuclear reactor does not have a switch. You can stop it generating electricity, but you can't turn off the heat."

The only option left to plant operators was pumping seawater into the containment buildings in a last-ditch attempt to cool off the inner containment vessel, which is made from concrete and steel. Nevertheless, steam pressure building up in three reactors have now caused explosions and deepening concern about the integrity of the reactor containment vessels.

"Unfortunately, it is extremely difficult to pump seawater into the containment vessel because there is too much pressure inside. There are pipes that can allows water to be pumped in, but right now the pumps are not working, and its not clear that the pipes are even connected," said Olson.

The way the wind blows

With Tuesday's third reactor explosion, officials are now waiting to see which way the wind blows. No one can says whether or not molten uranium and plutonium inside the reactors will burn through the inner containment vessel since rising temperatures inside can no longer be controlled. If the containment vessels are breeched, the Chernobyl scenario becomes a possibility, experts said.

If the containment vessels hold--either through luck or the process of venting steam to relieve the mounting pressures inside--then the remaining hazards will be the venting of radioactive air and radioactive fuel pools exposed by the hydrogen explosions.

"One hazard that no one is talking about are the nuclear fuel pools that were inside the containment buildings that blew up," said Olson. "I am dismayed that we have had no clear reporting yet from Japan about the fate of these radioactive pools."

After fueling reactors for up to six years, spent fuel rods are stored underwater for 10 to 20 years in pools at the bottom on the containment building. The water both cools the fuel rods and provides shielding from radiation. So far, Fukushima officials have not revealed the fate of these pools at the reactors where explosions have occurred.

Most of the Fukushima reactors have operated well beyond their expected 25-year life expectancy. The plant began operating in 1971. The No. 1 reactor was to have been decommissioned in 2011, but Japanese regulators recently gave operator Tokyo Electric Power a ten-year extension of its operating license for the reactor.

copyright ©2011 UBM Electronics,

A UBM company

All rights reserved To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.eetimes.com