Protests on the Navajo Nation have been in high gear ever since last week, when tribal members and activists got wind of a proposed settlement that aims to help quantify Navajo water rights on the Little Colorado River.

Trouble is, many Navajo citizens believe the settlement may actually erode the tribe’s sovereignty when it comes to maintaining a safe and sufficient future water supply.

The Navajo-Hopi Little Colorado River Water Rights Settlement Act of 2012 emerged from years-long negotiations between 30 stakeholders in the Little Colorado River basin, including the Navajo and Hopi tribes, industry and governments. It’s been introduced to Congress as Senate Bill 2109 by senators John McCain (R-AZ) and Jon Kyl (R-AZ), and has the support, so far, of Navajo Nation President Ben Shelly. The settlement’s proponents point out that it allows the Navajo Nation to use whatever water it can get from the C-aquifer and the Little Colorado River.

The C-aquifer underlies part of northeastern Arizona and stretches into New Mexico. It is tapped as a water supply by cities south of the Little Colorado River, including Flagstaff. According to an analysis by the Arizona Department of Water Resources, “north of the river the C-aquifer is too deep to be economically useful, or is unsuitable for most uses because of high concentrations of total dissolved solids.” For the most part, that’s the portion that overlaps with the Navajo Nation.

As for the Little Colorado River – a tributary of the Colorado – flow gages near Flagstaff and Cameron reveal there are about 163,000 acre-feet of water flowing toward the Navajo Nation in the Little Colorado, on average. “It fluctuates so much that the averages don’t do you a lot of good unless you’ve got storage,” pointed out Stanley Pollack, the Navajo Nation’s long-time water attorney.

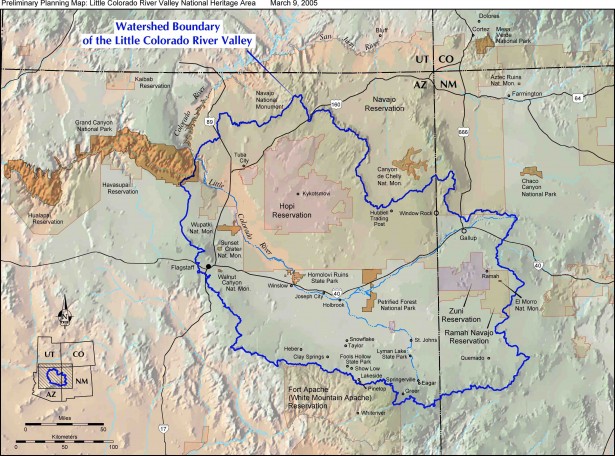

Little Colorado Watershed Boundary (www.archaeologysouthwest.org)

The heated concerns about the settlement stem mostly from its details – densely constructed obligations and waivers that even Pollack says are confusing and, in at least one case, poorly written.

The Navajo public will have its say soon, in a series of town hall meetings. But if the protest last week is any indication, the settlement is likely to face tough opposition.

On April 5, about 400 people crashed a meeting between senators Kyl and McCain and Shelly at a Tuba City restaurant. Videos of the confrontation between Shelly and the protestors reveal an angry exchange that some say came frighteningly close to the level of a riot.

Powerful Protest

Erny Zah, Shelly’s spokesman, expressed dismay at the volatile nature of last week’s protest.

“This isn’t about opinions,” he said. “We’re talking basic fundamental principals of Navajo teaching. There’s a fundamental respect that’s taught to us. That day showed that either we’re forgetting about who we are, or we just ignored who we are.”

Ed Becenti, a Navajo grassroots organizer and one of the protestors who was in Tuba City that day, disagrees with Zah’s assessment. Shelly is selling out his people by giving away their water, he said – he’s brought the derision on himself. As for the settlement the president is backing, Becenti is horrified: “This is almost like genocide,” he said. “We’re being manipulated into our own extinction. The other parties are hurting for water and they’re doing whatever they can to get to what we have left.”

Becenti said the negative reaction was fueled in large part because the protestors felt they’d been blindsided. Kyl announced the settlement bill in mid-February, and the news came as a shock to Becenti and his fellow grassroots community: “We looked at each other and said, ‘You know anything about that?’”

Nobody in the grassroots community got actual copies of the settlement until a week ago, just days before they began to hear rumors about a mysterious upcoming visit from McCain and Kyl. Activists say they haven’t had time to fully digest the language of the settlement, much less explain the English legalese to their Navajo-speaking rural elders. Despite that, they say a groundswell of opposition came together to greet the senators’ visit with lightning speed.

“There were Hopis and Navajos,” says Kim Smith, a community organizer and volunteer with the grassroots organization Diné CARE. “There were young people and elders. There were men and there were women. There was a very great energy of solidarity. There were elders there who were speaking up. They even told us some of our creation stories, how those connect to our clan system, and the water. That’s like a prayer. When you’re putting it out there in that way, it’s prayer.”

A Step Back?

Senator Kyl acknowledges in a public video about the bill that, “Legally, the Navajo Nation and Hopi tribe may assert claims to larger quantities of water [than are outlined in the settlement] but … they do not have the means to make use of those supplies in a safe and productive manner. “

Becenti disputes that. “In reality we do have a lot of water projects that we were talking about 30 years ago,” he said. “But every time we approach the United States government to approve them, they won’t.”

And Jihan Gearon, executive director of the Black Mesa Water Coalition, says the provisions that help shore up the future of the Navajo Generating Station are a direct affront to her group’s efforts to build renewable energy capacity across the reservation.

“As an organization, our goal is to shut down the Navajo Generating Station and transition to renewable energy development,” she said. The settlement, on the other hand, appears to be “part of this big strategy to keep the Navajo Generating Station going at the lowest possible cost. These things that they’re stipulating have nothing to do with who should be offered which water. Instead, they support unsustainable development that’s happening in northern Arizona.”

Some of the terms of the proposed settlement include building infrastructure to get water to two Navajo communities where people lack running water; both Kyl and Zah point to the Dilkon area, northeast of Flagstaff, as an example.

“There are going to be water supply issues in Dilkon,” Zah said. “With this plan, we would at least be able to get them some water.”

In his video, Kyl adds that communities in the eastern side of the Navajo Nation, near Window Rock, would benefit from the Navajo-Gallup water supply project, “one of 14 projects chosen by the president in October for expedited environmental review and permitting.”

But as the protesters are well aware, leaving the promised infrastructure projects up to Congress’s discretion – based in part on the availability of money – has rarely worked out in the favor of tribes.

Public Forums to Begin Soon

Despite all of the concerns, Pollack says there’s a major point about the settlement that’s getting lost.

“Typically there is no such thing as a perfect settlement,” he said. “The question is whether the settlement is better than the alternative: No settlement means we’re going to return back to the litigation that’s been ongoing for 33 years that’s made little progress. The Hopi tribe is asserting a paramount priority, saying they have water right superior to the Navajo nation. There isn’t an end in sight.”

And in Pollack’s view, the settlement isn’t bad: “The Navajo Nation is getting water rights to the Little Colorado River that do not have limits,” he said. “It’s getting rights to groundwater that do not have limits. If the Navajo Nation goes to court, the court is going to establish limits.” There are additional benefits, he said.

“Through this settlement, Colorado River water is being reserved for the Navajo Nation so that no other tribe can get allocated that water while Navajo and Hopi tribes settle their Colorado River claims. And it authorizes a feasibility study for the Western Navajo pipeline.”

Pollack said there’s time pressure to get the settlement passed before the 2012 presidential election: “This administration has made this settlement its number one priority for Indian water in the United States,” he said. “They are strongly behind this one. That’s a good thing.”

Even so, Zah, the Navajo spokesman, pointed out that both Kyl and McCain have pledged that the bill won’t be pushed through without Navajo and Hopi support.

“If the people decide that this is not what they want, they can lobby to their council delegates. There are water rights forums starting next week, and we want people to be educated when they make their decision,” he said.

Forums are scheduled across the Navajo Nation from 4 to 7 p.m. on the following days: April 17 in Tuba City, April 18 in Pinon, April 19 in Ganado, April 20 in Oak Springs, April 24 in Leupp, April 25 in Teesto and April 26 in Fort Defiance.

In addition, various grassroots groups are conducting ceremonies, meetings and seminars on water issues and SB 2109. Diné CARE’s Smith organized a water summit at the ceremonial grounds near the Dilkon courthouse on Friday. And Becenti is hosting a Navajo-Hopi Water Rights Symposium from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. today at the Navajo Nation Museum Auditorium in Window Rock.

***************

Addressing the Fears

Navajo Nation water attorney Stanley Pollack regrets that the Navajo-Hopi Little Colorado River Water Rights Settlement Act of 2012 is a bear to comprehend – and he knows that’s fueling some of the opposition to the related bill, SB 2109, that’s making its way through Congress.

“The language is not user friendly or tribal friendly,” he acknowledged. But Pollack says some of the settlement’s key terms are being misinterpreted, and he’d like to set the record straight.

*FEAR: The settlement requires the Navajo Nation to never sue for past or future water withdrawals or pollution from decades of coal mining on Navajo land, even though Peabody Coal and the Navajo Generating Station have caused documented damage to the Navajo Aquifer underneath the reservation.

“I don’t take it as a factual statement that there is damage to the aquifer,” Pollack says. “But let’s assume that there was damage to the aquifer. There’s nothing in this document that prevents the Navajo Nation from enforcing its lease agreements or water quality statutes.” Furthermore, he said, the settlement is very specific on which type of pollution gets a free pass: “A change in salinity or concentration of naturally occurring constituents of water. If somebody is discharging toxins, we haven’t waived anything. The only thing that is waived here is damage to water quality caused by withdrawal of the water itself.”

Pollack’s comments on this point are still raising red flags for some settlement critics. Anne Mariah Tapp, a law student at the University of Colorado in Boulder who is within weeks of completing her degree – and specializing in Native American issues – suspects that an industrial polluter could defensibly group just about anything as a “naturally occurring constituent.” And Vincent Yazzie, a Navajo activist and law buff, pointed out that there’s court precedent for interpreting waivers broadly, to the detriment of tribal enforcement power.

Pollack did say the water quality waiver is standard for Indian water settlements, and identical to a waiver in the White Mountain Apache settlement. “We fought for years and years to try to come up with waivers that were in plain English that people could understand, and we got nowhere,” he said.

*FEAR: According to the settlement, the Navajo Nation must extend a deal for another 34 years that gives up to 50,000 acre-feet of water, for free, to the coal-fired Navajo Generating Station.

The actual proposed deal, Pollack says, is that “if the Navajo Generating Station is going to operate … the water supply for that can come from Navajo Nation upper basin [Colorado River] portion, to which the Nation consented in 1968. The agreement doesn’t say anything about whether this water is free or whether the nation can charge for it. We’re not giving them something they don’t already have.”

He says the settlement isn’t contingent on the Navajo Generating Station getting its water. But there is a tradeoff – if the Navajo Generating Station doesn’t get its water, then the Navajo Nation won’t get Colorado River water for the planned Navajo-Gallup water supply project what would supply water to dry communities near Window Rock. That tradeoff represents a loophole by which the Navajo Nation can get some Colorado River water even though there’s been no settlement for Navajo water rights on that larger river. The state of Arizona advocated the tradeoff, because it wants a guaranteed water supply for the Navajo Generating Station.

Tribal activists are pointing out that the Colorado River water for the Navajo-Gallup water supply project was actually promised in a previous settlement for water rights on the San Juan, so many are confused about why it’s being used as a carrot in the current negotiations.

Still, Pollack said, “if the Navajo Nation says no to the Navajo Generating Station, which is the Navajo Nation’s right as a sovereign, this settlement is still effective.”

Yazzie takes that reassurance with a grain of salt: “A Congressional mandate that the Navajo Generating Station gets water on favorable terms” would be “hard to overturn once in place,” he said.

*FEAR: The settlement bars the Navajo Nation from ever selling Little Colorado River water.

“There is not a tribe in Arizona that has the ability to market its on-reservation decreed water rights,” Pollack said. “Out of, I think, 10 water right settlements, every one of those settlements has a provision against marketing the water, except for those tribes that receive project water. This settlement is just like all of the other settlements in Arizona.”

*FEAR: The settlement negates the tribe’s senior status with regard to its aboriginal water rights in the basin.

“I keep hearing that we’re waiving aboriginal rights,” Pollack said. “Frankly, I don’t understand what they’re getting at there. The aboriginal right is a right that is limited to those aboriginal uses. Those historic uses are quantified and they’re going to be included in the decree; that’s part of the leverage we have to settle our claims.”

He said the provision of concern “refers to the fact that the Navajo Nation can’t come back and assert additional claims; it’s a settlement. It’s supposed to be permanent.”

*FEAR: The settlement absolves the federal government of its trust responsibility to safeguard water quality in the N-aquifer, which supplies water to communities in the Black Mesa area.

“I don’t believe that is true,” Pollack said. “I’m going to concede that language is really poorly written. I’ve already talked to them about having to rewrite that and explain that.” Still, he said, “I don’t think the federal government has waived its trust responsibility in this settlement. This settlement does not redefine those responsibilities.”

© 1998 - 2012 Indian Country Today. All Rights Reserved To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.indiancountry.com