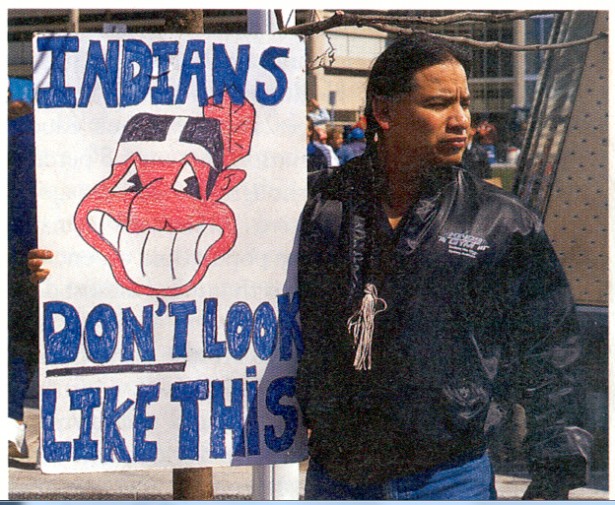

Major League baseball is a game of hallowed traditions. For the Cleveland Indians, the traditional throwing out of the first pitch every season is accompanied by a few other time-honored rituals, which include throwing out insults to Native Americans, some of whom come to the team’s stadium each spring to protest the team’s name and its cartoonish logo and mascot, Chief Wahoo. “We’re going to hold up signs, get ridiculed for about two hours and then we’re going to go home,” Sundance, the director of Cleveland AIM, told Akron News Now before this year’s demonstration.

Those Native American protestors who gather at the ironically named Progressive Field—some of them members of the Cleveland American Indian Movement (AIM) and the Committee of 500 Years of Dignity and Resistance—have not been met with open arms or friendly words. Cleveland’s baseball fans have hurled beer cans and spat on them. The protesters have been called stupid and “Custer-killers”—although it’s not absolutely clear whether that last description is an insult or a compliment. Cleveland AIM calls the use of the Chief Wahoo mascot “bigoted, racist and shameful,” and the Committee of 500 complains that the logo is a negative stereotype against indigenous people.

Supporters of the Cleveland Indians insist that the team’s name and the logo bring honor to American Indians, and heighten awareness to the plight of Native people across the nation. The Cleveland Indians organization did not return calls from ICTMN seeking comment on this issue, but in an April 4 story about the controversy, team spokesman Bob DiBiasio told the Cleveland Plain Dealer that he respects the opinions of the protesters, but as to whether the team symbols are racist or not, he said “it is an individual perception issue… When people look at our logo, we believe they think baseball.”

Sundance reports that things can get pretty tense outside the gates of the Cleveland stadium on Opening Day. “We have been actively protesting at the stadium since 1973,” he says, adding that the Cleveland AIM was, “formed in 1972 and in that same year we filed a lawsuit against Cleveland baseball for slander and libel… Obviously it was unsuccessful, because we are still standing out there today.”

He says the anti-Wahoo protestors are often joined by members of the Native organization known as The Peacekeepers, who stand as a human barrier to protect them from an often unruly and inebriated crowd. “There were a couple of years in the recent past when The Peacekeepers were not there. In one of those years there was an assault,” he says. “The young gentleman who was assaulted came as a bystander… He had a video camera and was doing a project for a class.”

Robert Roche, Chiricahua Apache, the Executive Director of the Cleveland American Indian Education Center, and a former director of Cleveland AIM, also witnessed this ugly incident. “He was a white student from Cleveland State, and an Iraq War vet. He was filming the demonstration and we noticed one guy standing behind us. When you are at these demonstrations, you try to remain alert because you never know what might happen. The student was just standing there, asking questions… This guy assumed the student was with us and punched him in the mouth.”

“It was shocking that the police arrested the guy—We have had altercations throughout the years, and the police have never done anything. But it was a white guy hitting a white guy [this time].”

Roche has been coming to the Opening Day protests at the Cleveland ballpark since 1973. (He also claims to be the first person to publicly burn in effigy an image of the Chief Wahoo logo.) “When we had demonstrations at the old Cleveland Indians Stadium there were always chances for physical altercations,” he says. “People used to throw beer cans at us; they would spit on the women and spit on the kids. They always seemed to pick on the little kids and the women. I used to get in the middle of it to try and defuse the situation but [the police] barricaded us so it would be harder for the fans to get to us.”

Roche says he has been taken to police headquarters many times after a demonstration, but never arrested. “I told them to arrest me, they wouldn’t do it,” he says. “If they arrested me it would bring unnecessary publicity to them. They’ve always reprimanded me and let me go.”

Ferne Clements is the Secretary and Interim Chair of the Committee of 500 Years of Dignity and Resistance, a Native-friendly multi-cultural organization dedicated to enhancing and protecting the cultural human rights and heritage rights of indigenous people living in Northeast Ohio. Though Clements is not of Native descent, she is a strong advocate against the use of the Cleveland Indians name and logo. “The logo is a negative stereotype against indigenous people,” she says. “What is sacred to the indigenous people is made a mockery of. If there was an African-American logo similar to a black Sambo, or if it was a Jewish character, it would not have lasted this long.”

Clements has been coming out for Opening Day for 20 years.

“There are a lot of verbal incidents. The older generation will sit there, glare at us and tell us to get a life. The younger, they will make the wahoo sound, and will yell and holler at us.”There are some baseball fans that defend the team, and denounce racism. One gentleman recently wrote a letter to the Plain Dealer arguing that the Cleveland Indians name and Chief Wahoo logo were meant to honor American Indians. In his letter, he wrote, “The name and mascot of the Cleveland Indians inspire positive recognition of this country’s priceless Native Americans. The names and symbols being protested conjure appreciation of such qualities as strength, endurance, prowess, fairness and cohesion in competition. Any team that embodies these is certainly formidable in the ballpark, just as tribes and nations of Native Americans are.

“As an Indians fan, I find Chief Wahoo and the nickname Tribe a homage to heroics as well. Although baseball is not war, I cannot help but be reminded of the Pima Indian who raised the flag on Iwo Jima or, more recently, a member of the Hopi tribe, Spc. Lori Ann Piestewa, who was the first woman killed in the Iraq War and the first Native American woman to die in combat while serving with the U.S. military.

Native Americans are uniquely American. So is baseball. There is no slur here. There is full recognition that such Americans are an indelible part of America’s persona and heritage,” he wrote.

Clements has a short and pungent rebuttal: “That is crap,” she says. “They were trying to say the team honors Louis Sockalexis [one of, if not the first indigenous players in the major leagues] yet Sockalexis was never mentioned when the team name was changed to the Indians. We looked into the archives of the newspapers during that time and there was no mention of honoring Louis Sockalexis.”

Sockalexis was one of a handful of Native Americans to play professional baseball in its early days. He signed with a precursor of the current team, the Cleveland Spiders, in 1897, but only lasted two years. The team’s name was changed to “Indians” in 1915, the year after the Boston Braves won the World Series.

Ellen Staurowsky, a Drexel University professor who has researched the role of race in sports, wrote about the Cleveland team chose the name “Indians” in a 1998 journal article for The Sociology of Sport. She also wrote about Sockalexis, citing an 1897 newspaper that said he was sometimes taunted by fans because of his heritage.

Staurowsky, who says she has observed some of the protests outside the Cleveland ballpark, notes that the racist behavior of fans from over 100 years ago lives on. “I’ve always found it compelling that the club has claimed that the whole purpose of the naming is to honor an American Indian, and the behavior of the fans when they’re confronted with actual American Indians protesting is quite contrary to honor,” she told CNN’s Stephanie Siek. “The fact that this has been going on for years and the behavior essentially hasn’t changed speaks to a level of racism that is so very difficult to eradicate.”

“You cannot honor people you do not respect,” Sundance argues. “As a people, we demand dignity. We are not asking for honor. When a native person stands up and says, ‘Hey this is not right; no one gave you the right to use our pseudo-name, category or images,’ people say, ‘Shut up and listen. We are honoring you. You are too stupid to understand this.’

“We are not too stupid to understand what is going on. We have seen Indian heads used to dehumanize us and to put out a call for mass-murder against us for the past 500 years. To see a bunch of drunken people with Indian heads shouting slurs and chanting ‘Go Indians!’ is not an honorable environment and it is not an honorable experience.”

Roche makes another point about this so-called honorific: “When you honor somebody, you really might want to get their approval. That is not happening. The problem is that people have been brought up generation after generation, being told that Native Americans are being honored. But they have never heard our side of it.”

There has been some talk of “retiring” Chief Wahoo, but that will not silence the protests. Clements, Sundance and Roche agree that the only right thing for the Cleveland Indians to do is to change their name and their logo. “The Cleveland baseball team needs to change the team name and logo to something that does not reference native people,” says Sundance.

“If they change the logo and not the name, it would not change anything whatsoever,” says Clements, who points out that the tide is clearly turning, albeit slowly, on this issue—many schools and universities are changing logos that are disrespectful to Native Americans.

Roche has an intriguing incentive for the team to make the switch, one that might win over even the most racist Cleveland fan. If they change their name and logo, he says, they might make history by doing something no Cleveland baseball team has ever done: win a World Series. “Russell Means himself put a curse on the team [in ‘96],” explains Roche. “[We believe] the new stadium was built on Indian burial grounds, [so] they are never going to win the World Series. Never.”

© 1998 - 2012 Indian Country Today. All Rights Reserved To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.indiancountry.com