Advance could turn wastewater treatment into viable electricity producer

By Darren Quick

August 14, 2012

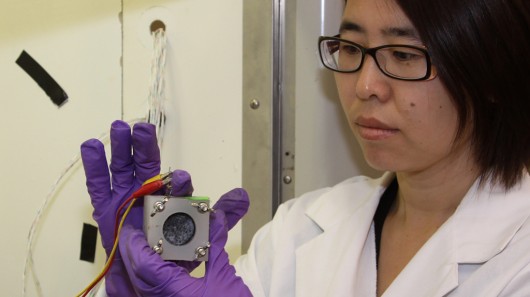

Research at Oregon State University by engineer Hong Liu has discovered improved ways to produce electricity from sewage using microbial fuel cells (Photo: Oregon State University)

In the latest green energy – or perhaps that should be brown energy – news, a team of engineers from Oregon State University (OSU) has developed new technology they claim significantly improves the performance of microbial fuel cells (MFCs) that can be used to produce electricity directly from wastewater. With the promise of producing 10 to 50 times the electricity, per volume, than comparable approaches, the researchers say the technology could see waste treatment plants not only powering themselves, but also feeding excess electricity back to the grid.

The electricity-generating potential of microbes has been known for decades, however, it is only in recent years that efforts to increase the amount of electricity generated to commercially viable levels has started to bear fruit. In MFCs, bacteria are used to oxidize organic matter – be it in wastewater, grass straw, animal waste, and byproducts from such operations as the wine, beer or dairy industries – which produces electrons that run from the anode to the cathode within the fuel cell to create an electrical current.

By adopting a number of new concepts, including reducing the anode-cathode spacing, and using evolved microbes and new separator materials, the researchers say they have been able to produce MFCs that produce more than two kilowatts per cubic meter of liquid reactor volume. The researchers point out this power density is much higher than has been achieved previously and could see the new technology replacing the widely used “activated sludge” process that has been used for almost a century.

While the power density of the new technology is impressive, its potential would be hampered somewhat if it was lacking in the water treatment department. Thankfully, the researchers claim it treats wastewater more effectively than the alternative approach used to generate electricity from wastewater, which is based on anaerobic digestion and produces methane and hydrogen sulfide.

The team has proven the system “at a substantial scale in the laboratory” and is now seeking funding to scale things up with a pilot study. A contained system that produces a steady supply of certain types of wastewater that would provide significant amounts of electricity, such as a food processing plant, is seen as an ideal candidate for such a test.

A pilot study would also assist the team in efforts to reduce the high initial costs of the system by identifying potential reductions in material costs, further optimizing the use of the microbes, and improving the system’s function at commercial scales. If the high initial costs can be brought down through such advances, the OSU team estimates the construction costs of their new technology will be comparable that that of activated sludge systems, even without taking into account future sales of electricity generated at the facility.

“If this technology works on a commercial scale the way we believe it will, the treatment of wastewater could be a huge energy producer, not a huge energy cost,” said Hong Liu, an associate professor in the OSU Department of Biological and Ecological Engineering. “This could have an impact around the world, save a great deal of money, provide better water treatment and promote energy sustainability.”

While turning wastewater treatment from an electricity consumer to an electricity generator has obvious benefits for developed countries, the potential for the technology holds even greater promise in developing countries where both electricity access and sewage treatment is lacking.

The OSU team's findings appear in Energy and Environmental Science.

Source: Oregon State University