In our time, we can remember where we were when a few transformative events occurred—the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the killing of John Lennon. The explosion of Challenger, the tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square.

For our grandparents, the psychic notch in time was made when they finally heard about the event rather than when it happened, but according to my grandparents there was still that feeling upon hearing the news that everything had changed. For them, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was like the World Trade Center attacks on 9/11, no less shocking because they did not get the news immediately.

According to my grandparents, the news of one man dying in August of 1935 struck them like the deaths of both Kennedy and Lennon, a simultaneous earthquake in both politics and entertainment. The New York Times devoted 13 full pages to coverage of this death two days after it happened, almost four pages the next day, and the ink kept flowing for more than a week. On the Times‘s editorial page, the editors with whom that man had clashed many times opined: “He came to hold such a place in the public mind that, of his passing from the stage it might be said…that it will ‘eclipse the gayety of nations.’ Let us hope…some one may arise to help us as he did to keep our mental poise, to avoid taking all our national geese for swans, and by wholesome laughter make this world seem a better place to live in.”

President Franklin D. Roosevelt said, “His appeal went straight to the heart of the nation. Above all things, in a time grown too solemn and somber he brought his countrymen back to a sense of proportion.”

On the day of his funeral, 51,000 people waited five hours in the hot Los Angeles sun for a brief chance to pay their respects. Every movie theater in the country went dark for two minutes; the CBS and NBC radio networks observed 30 minutes of silence in his honor.

The man himself would probably have been most moved by a story recounted by one of his many biographers: “In Locust Grove, Oklahoma, half a dozen Cherokees were building a fence when an old man drove along the road to tell them the news.… After a time, some of the Indians spoke of how they had known Will or remembered a favor he had done for someone. Then one said, ‘I can’t work any more today,’ and all of them stacked their tools and quietly walked away.”

Will Rogers was born on November 4, 1879, in Oologah, Cooweescoowee District, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory. He came into this world with a slightly more pretentious handle than “Will”—William Penn Adair Rogers. He was born, as is Cherokee custom, into his mother’s Paint Clan. His family was typical of the intermarriage that had been going on in the Cherokee Nation starting in the 17th century. His Paint Clan mother, Mary America Schrimsher, was one-fourth Cherokee by blood. His father, Clement Vann Rogers, known as Clem, was one-eighth. Then as now, a person was either a Cherokee citizen or not, regardless of blood quantum, and the Rogers family was. His father attended the Cherokee Male Seminary and then served the Cherokee Nation as a judge and later as a senator. His mother studied music at the Cherokee Female Seminary near Tahlequah. Rogers used to say, “I had just enough white in me to make my honesty questionable.”

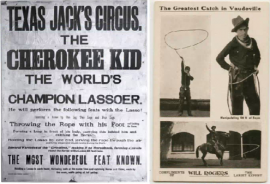

Rogers said he was in South Africa baby-sitting cattle when he joined Texas Jack’s Circus.

Indian Territory was supposed to be so forever, but by the time of Rogers’s birth, white people already outnumbered Indians in this refuge for exotic Natives of North America, and it only got worse over time. This is how the 1890 census broke down the population of the land occupied by the Five Tribes: 103,393 whites, 18,636 Negroes and 50,055 Indians. The shooting part of the Indian Wars was winding down by the time Rogers was born, but 1879 was the year of Dull Knife’s revolt at Fort Robinson. Quanah Parker had surrendered in 1875; Sitting Bull would surrender in 1881. When Geronimo gave it up in 1886, the robbery with a six-gun stopped and what Woody Guthrie (who named his first-born son after Rogers) would later call robbery with a fountain pen began. The Dawes Act was passed in 1887 and it led, over time, to the theft of Indian property on a scale that far surpassed anything accomplished by military action. Rogers was 9 years old when white settlers lined up on the border of Indian Territory to run for the “free Indian land.” Cheating was so rampant in this land rush that the people who staked their claims in advance were dubbed, “sooners,” a nickname from which contemporary Oklahomans still derive a perverse pride.

After the Dawes Act worked its malevolent magic, Rogers and his father Clem were left with an allotment of 148.77 acres—78.84 for Rogers and 69.93 for Clem—all that remained of a 60,000-acre ranch Clem had worked under the Cherokee law of usufruct—and a family compensation amounting to $365.70. Clem had become fairly prosperous a second time (having lost everything in the Civil War) purchasing cattle cheaply in Texas, fattening them on the lush grass of the Verdigris River bottomland, and selling them at the railheads.

When Rogers was growing up at the turn of the 20th century, the divide between “cowboys and Indians” in popular culture was already a load of hooey. Cowboys were Indians and Rogers, like many Indians, grew up with the skills of a cowboy, principally riding and roping.

Eight years after the last Oklahoma land rush, the unknown Oklahoma Cherokee set out to cowboy his way around the world. He went to Argentina, then as now famous for cattle ranching and the Argentine version of cowboys, the gauchos. He found the gauchos no better-paid than the cowboys of Indian Territory and the Spanish language daunting, about which he remarked, “I think I can say six words—did know seven and forgot one.” Running out of money in Argentina, he got a job on a ship headed for South Africa “baby-sitting” a load of livestock.

It was in South Africa that the cowboy first became an entertainer and, to hear Rogers tell it, was forever ruined for real work. He joined Texas Jack’s Wild West Show with an act composed of the rope tricks he had perfected back on the ranch in Oologah. Texas Jack billed Rogers as the Cherokee Kid, a moniker that stuck for many years. Rogers wrote to Clem back home that the entertainment business “will enable me to make my living in the world without making it by day labor.” He soon had printed cards

Rogers had a syndicated newspaper column, a popular radio show and made movies that delighted paupers and presidents, including FDR (far left).

for fans that read:

THE CHEROKEE KID

FANCY LASSO ARTIST AND ROUGH RIDER

TEXAS JACK’S WILD WEST CIRCUS

Carrying an enthusiastic reference letter from Texas Jack, Rogers was hired by the Wirth Brothers Circus for a tour of Australia and New Zealand, still billed as the Cherokee Kid. There might have been a glimpse of his later role as unofficial American ambassador to the world in a letter he wrote home from Sydney, in 1903: “I was always proud in America to own that I was a Cherokee, and I find on leaving them that I am equally as proud to own that I am an American.… I have had arguments with every nationality of man under the sun in regard to the merits of our people and country.… ”

Roping with the circus in New Zealand, Rogers earned enough money for a third-class ticket back to the United States, but he reached San Francisco broke and had to hitch back to Indian Territory on a freight train.

If Rogers had died hopping a freight—and lots of young men did in those days—his loss would be little-noted nor long-remembered outside the Cherokee Nation. Instead, this 10th-grade dropout went on to publish more than 2 million words in his lifetime, including a syndicated weekly newspaper column from 1922 until his death in 1935 and a daily “squib,” a precursor of the modern blog or Twitter feed, that appeared on the front page of most major newspapers starting in 1926.

This man who never held political office—except, briefly, as honorary mayor of Beverly Hills, California—would become a personal friend of every president from Teddy Roosevelt to Franklin D. Roosevelt. He practiced political punditry with a prickly sense of humor, in a manner comparable to Mark Twain before him and Jon Stewart in our day.

Rogers claimed that he once approached Warren G. Harding, the president he had the least relationship with in his lifetime, with the offer to “tell him all the latest political jokes.” He said Harding replied: “ ‘I know ’em, I appointed most of them.’ So I saw I couldn’t match humor with this man.”

Of Congress, Rogers said, “Every time they make a joke, it’s a law.… And every time they make a law, it’s a joke.”

His comedy came from his peculiar position as an outsider who made regular and long-lasting friendships with insiders. He was an outsider by choice, although he had to work a bit to discourage people from electing him. On one occasion, Rogers asked his audience: “Will you do me one favor? If you see or hear of anybody proposing my name either humorously or semiseriously for any political office, will you maim said party and send me the bill?”

Rogers’s name was placed in nomination for president at the 1924 Democratic convention, an honor he took in good humor. Then in 1928, he had a semiserious brush with national office when the Republicans nominated an Indian, Charles Curtis, Kaw, as the running mate for Herbert Hoover, and the suggestion was that the Democrats put a Cherokee on the national ticket. Rogers was not interested. In 1932, Oklahoma delegates at the Democratic Convention in Chicago cast their 22 votes for Rogers as “favorite son” to lead the presidential ticket. Rogers, who was in town to write about the convention, joked that he took a nap after the first ballot and “somebody touched me for my whole roll, took the whole 22 votes, didn’t even leave me a vote to get breakfast on.”

Rogers was on what would have been his fourth trip around the world when his plane went down.

The only time Rogers went along with being a candidate was his 1928 run for the Anti-Bunk Party, under the slogan, “Whatever the other fellow don’t do, we will!” He promised that if elected, he would resign—probably the most serious part of his candidacy. He was, however, endorsed by Henry Ford, Babe Ruth and Ring Lardner, among others. He was deeply interested in politics, but his interest was as a citizen and a commentator. He would have cringed at being called a “public intellectual,” as would his most vociferous critics, who considered him a hayseed from what we call in modern parlance “fly-over country.” Whatever politicians thought of his intellect, there was no doubting his influence on public opinion. His jokes often had a cutting edge, and the blade might have been turned toward either political party, usually the one in power.

His friendships colored his observations, but he never claimed otherwise. His famous remark that he never met a man he didn’t like was a motto he lived by, and it led him into contradictions. He was very much opposed to women voting or participating in politics. However, he became close friends with Alice Roosevelt Longworth, daughter of Theodore Roosevelt, who was prominent in U.S. politics all her life, and Nancy Astor, the first woman to sit in the British Parliament. When he talked with or wrote about these women, it was as if his ideas about women in politics did not exist.

His father was a former slaveholder and ardent segregationist, but show business brought Rogers in contact with black people, and it simply wasn’t in the man to hate people he knew. He played for segregated audiences when he had to because that was the fact of the times, but he also played for blacks in separate performances.

He despised crookedness, but once the crooks were caught and put on trial, he found it hard to keep after them, most famously in the Teapot Dome scandal, when he found it much easier to denounce the stealing than to demand punishment for the thieves. He even declined to dance on the political grave of Albert Fall, one of the worst Indian fighters every to serve as Secretary of the Interior. Fall had instituted the infamous “Courts of Indian Offenses” to suppress Indian religious expression and violated the federal trust responsibility by working to separate Pueblo Indians from their land in his native New Mexico. But when he was convicted of bribery in the Teapot Dome scandal and became the first cabinet member to go to prison, Rogers criticized “sending old man Fall to the pen.… Course everything wasn’t exactly on the up-and-up, but that is one case that was tried entirely by politics.”

Perhaps the most striking contradiction was Rogers’s friendship with Theodore Roosevelt, under whose administration the Five Tribes experienced the most dire results of treaty abrogation. On the economic front, the Dawes Act destroyed tribal land bases. On the political front, the treaty promises that Indian Territory would never become part of a state without tribal consent were shredded with the admission of Oklahoma to the union.

While he took no personal umbrage against Roosevelt, Rogers had plenty to say about the thievery: “They sent the Indians to Oklahoma. They had a treaty that said, ‘You shall have this land as long as grass grows and water flows.’ It was not only a good rhyme but looked like a good treaty, and it was till they struck oil. Then the government took it away from us again. They said the treaty only refers to ‘Water and Grass; it don’t say anything about oil.’ ”

Taking the side of ordinary people, particularly farmers, in the Great Depression, Rogers personally lobbied President Herbert Hoover against the Smoot-Hawley tariff bill, which modern economists agree only deepened the Depression. Hoover signed the bill anyway. In spite of that, Rogers did not attack Hoover personally nor did he encourage those who did. He just continued telling the truth though his humor, as in his remark that Argentina “exports meat, wheat and gigolos, and the United States puts a tariff on the wrong two.”

He also differed with Hoover on the matter of government backing for the Red Cross, which had taken on feeding Americans who, Rogers knew from his travels, were starving. While he still avoided direct attacks on Hoover, he was moved to step outside his cowboy humorist persona: “The stock market is picking up, so that makes the rich boys feel a little better. Lots of appropriations bills for government expenditures have been passed. Business in general in the last four or five weeks looks better. But, all that has nothing to do with the folks that the Red Cross has to feed.

“United States Steel can go to a thousand and one, Auburns to a million, but that don’t bring one biscuit to a poor old Negro family of 15 in Arkansas, who haven’t got a chance to get a single penny in money till their little few bales of cotton are sold away next fall.”

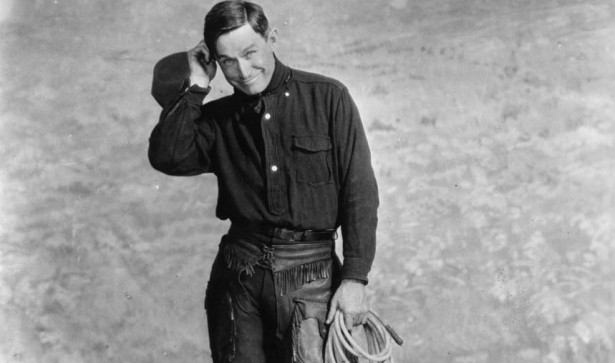

During the Depression, Rogers put his money where his mouth was, with thousands of dollars and many benefit performances, but he kept after the government to do what he felt governments needed to do. His other contribution to the public weal during the gloom of the Depression was his films. He had progressed from Wild West shows to vaudeville to silent films, but his movie career really came into focus with the talkies, in which he often ad-libbed lines and, like many box-office successes, always sounded a whole lot like himself. His films did not impress the critics, but in 1934 he was the top box-office draw in the country. In the next year, the year of his death, only Shirley Temple beat him. One of his many biographers, Richard M. Ketchum, wrote that “the talkies he made ran to a pattern. In them he usually played a thinly disguised version of himself: a rustic, somewhat seedy common man, an underdog speaking out against wealthier, unscrupulous characters. He was the kindly, impractical philosopher, a sort of deputy of the American conscience, reflecting the innate honesty and idealism of the plain folks of the land.”

Rogers never got to see the end of the Depression. On August 15, 1935, he was off on what might have become his fourth trip around the world, with his friend Wiley Post at the controls of an aircraft custom-built for the trip. Over a lagoon the indigenous people call Walakpa, more than 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle, the plane lost power and crashed during a water takeoff.

Rogers was 55 years old. He was survived by his wife, Betty, and three of their four children. He left many books, newspaper articles, radio broadcasts, and films to the world in general, and inspiration to generations of Cherokees. Having Rogers suddenly yanked from the pages of every major newspaper, off network radio and from the top of the motion picture business created a psychic notch in the reality of everyone who lived through the event. For those of us born later in still largely rural Indian country, his life—outsized in impact, if not duration—remains transformative in our understanding of ourselves and our sense of how much is possible. His metamorphosis from cowboy to entertainer to political force to American icon is a magical story.

Our telling of that story will continue with how the Indian cowboy conquered first New York City media and then Hollywood, rendering his Oklahoma drawl the narrative soundtrack for a generation.

The author gratefully acknowledges the research assistance of Steve Gragert, director of the Will Rogers Memorial Museums in Claremore, Oklahoma.

© 1998 - 2012 Indian Country Today. All Rights Reserved To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.indiancountry.com