It will be an astronomical spectacle for the ages. On June 5 and 6, Venus will undergo a solar transit—for the last time in our lives.

A transit occurs when a planet passes in front of the sun, just as the moon passes between Earth and the sun during a solar eclipse. The exact date that Venus will do so depends on your vantage point. Viewers in the Western Hemisphere will see the transit at sunset on June 5, while Eastern Hemisphere observers will see it around sunrise on June 6.

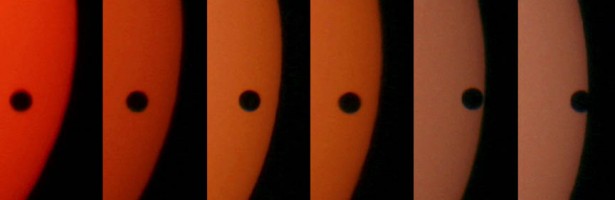

Venus, being much farther away than the moon, will not even remotely cover the sun during this journey. Instead, it will pass across our home star as a small black dot. Nevertheless, this process will result in a slight dimming of the sun, scientists say.

Transits of Venus occur in pairs, eight years apart, once a century. This is the second half of this century’s pairing; the next one doesn’t occur until 2117. The 20th century missed Venusian transits entirely, as the previous pair took place in December 1874 and December 1882.

During a transit of Venus, the sun, Venus and Earth also align in a straight line, according to the website Transit of Venus.

Venus was prominent in many ancient cultures but was especially important to the Mayans in Mexico and Central America. Even without telescopes, the Mayans were able to predict the movements of the spectacular object known popularly as the morning (or evening) star with great accuracy, thousands of years into the future. They may not have mapped a transit per se, but they knew where the planet was going to be, and when.

The Mayans venerated Venus as the basis of the god Kukulkan, elsewhere known as Quetzalcoatl. Unlike its modern, Western interpretation as the planet of love, the glittering orb was at that time associated with war. The Mayans even used its appearance to decide when to wage it. The evening version was especially related to war calculations, notes the website AuthenticMaya.com.

Several buildings in the iconic Mayan cities of Chichen-Itza and Uxmal are oriented toward Venus’s path along the ecliptic, and the planet’s journey to and fro across the sky was calculated as far as 7,000 years into the future. As discoveries in the jungles of Guatemala recently made clear, the calculations were scrawled on a wall in a small room thought to be that of the town’s scribe. Until this discovery was made in March, the Dresden Codex contained most comprehensive writings on Venus from the pre-Columbian era.

Known as Chak Ek’, Venus “was the astronomical object of greatest interest,” AuthenticMaya.com notes. “The Maya knew it better than any civilization outside Mesoamerica.”

In fact, Venus was considered more important than the sun in Mayan calculations.

“They watched it carefully as it moved through its stations,” says AuthenticMaya.com. The ancients carefully noted the 584 days it takes for Venus and the Earth to line up “in their previous position as compared to the sun. It takes about 2,922 days for the Earth, Venus, the sun, and the stars to agree.”

The Mayans even observed Venus in the daytime.

Although there are those in the indigenous world who will not watch this rare celestial event because of its shadowy connotations and a taboo (among the Navajo, at least) against viewing the sun, many people will be transfixed, and transit of Venus viewing parties abound. Just remember: Never stare directly at the sun. Instead, use a pair of sun-filtering goggles (the same ones one would use during a solar eclipse) or project the image through binoculars or a telescope onto the ground in front of you.

© 1998 - 2012 Indian Country Today. All Rights Reserved To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.indiancountry.com