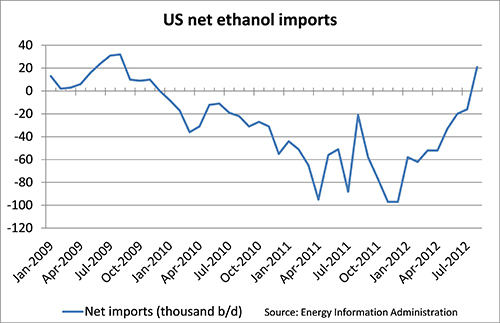

After a terrible summer for US ethanol producers, the country has shifted from net ethanol exporter to net importer for the first time in nearly three years.

The US imported 21,000 barrels per day more ethanol in August than it exported, according to the latest stats available from the Energy Information Administration’s Petroleum Supply Monthly report.

Until then, ethanol exports had exceeded imports every month since December 2009, when they were evenly balanced.

The steep decline in monthly exports isn’t much of a shocker, given the terrible margins US ethanol producers have faced since a severe drought started baking Midwestern corn fields in May.

Every few weeks since, another ethanol maker has announced the decision to slow or idle its production.

As Murray Campbell, the head of Georgia’s only corn-based ethanol plant, told Platts in October: “Looking at what’s on the market now with the basis bids, we just decided we’d better let the market sort of straighten itself out right now, as thin as margins are and non-existent.”

Before the drought, the plant owned by Southwest Georgia Ethanol was cranking out more than its nameplate annual capacity of 100 million gallons. Now it sits idle while Campbell waits out high corn prices.

Bob Dinneen, president of the Renewable Fuels Association, one of two big ethanol trade groups in Washington, said next year might look just as bleak for the industry.

“It’s going to be a pretty tough year,” he told reporters Friday. “The economics right now are pretty challenging. But the demand for ethanol remains very strong and what you have today is producers looking to squeeze every drop of profitability out of the kernel, every drop of profitability out of their asset at the ethanol plant.”

Dinneen said the ethanol industry would emerge from the drought stronger and more efficient.

“That’s what happens when you have to go through these type of situations,” he said. “It’s getting through it that’s always a challenge.”

Dinneen considers it possible that more plants will slow production or shut, even though they’re “pretty down near the bottom now, as near as I can tell.”