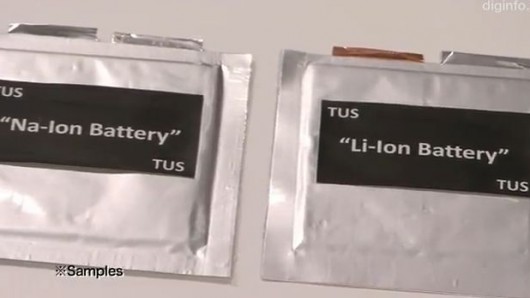

Researchers from the Tokyo University of Science have found pyrolyzed sucrose to be a surprisingly effective material for the anode of sodium-ion batteries (Image: Diginfo)

Researchers at the Tokyo University of Science have turned to sugar as part of a continuous effort to control Japan's growing import costs associated with building lithium-ion batteries. It seems that sugar may be the missing ingredient for building rechargeable batteries that are more robust, cheaper, and capable of storing more energy.

Lithium-ion batteries are ubiquitous in portable electronics, but concerns over rapidly growing demands for lithium – a metal that is mainly found in politically sensitive regions such as Bolivia, Chile, Argentina and China – have pushed countries like Japan to try and develop viable alternatives for a cheap, high-performance rechargeable battery.

Sodium-ion batteries have been put forward as one of the possible successors to lithium-ion technology. Among their advantages, they promise to be more durable and cheaper to manufacture. However, being in an early developmental phase, their performance isn't currently quite up to par.

Associate Professor Shinichi Komaba and his team have been working on narrowing this performance gap and recently discovered that sucrose – the main constituent of sugar – can be easily made into a cheap and effective material for the anode of a sodium-ion battery.

The team heated sucrose to temperatures of up to 1,500 °C (2,700 °F) in a controlled oxygen-free atmosphere, a process known as pyrolysis. The result is a hard carbon powder that, when embedded in a sodium-ion battery, can achieve a storage capacity of 300mAh, 20% higher than conventional hard carbon.

While this is just one more step toward developing an effective sodium-ion battery, Komaba predicts that his group could achieve their final objective of a commercially competitive battery in around five years.

The video below, provided by Diginfo, is a short recap of the findings.

Sources: Diginfo, Stanford University