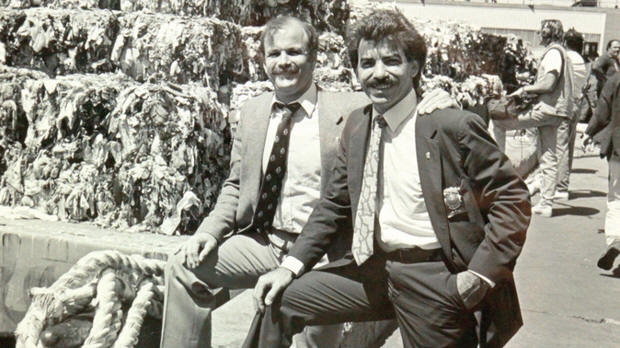

Courtesy, Vito Turso Vito Turso of

the New York City Department of Sanitation, right, and

then-Sanitation Commissioner Brendan Sexton stand in front of

bales of Mobro 4000 waste at the Southwest Brooklyn Incinerator

dock. After an embarrassing 6,000-mile journey, the waste was

incinerated and the ash residue buried in Islip on Long Island.

Courtesy, Vito Turso Vito Turso of

the New York City Department of Sanitation, right, and

then-Sanitation Commissioner Brendan Sexton stand in front of

bales of Mobro 4000 waste at the Southwest Brooklyn Incinerator

dock. After an embarrassing 6,000-mile journey, the waste was

incinerated and the ash residue buried in Islip on Long Island.

On March 22, 1987, a tugboat towed a barge piled high with bales of trash away from a pier on New York's Long Island. For the most part, no one noticed. It wasn't unusual for New York to export its garbage; this load of municipal waste, bound for a landfill in North Carolina, was as boring as they came.

Months later, everyone was talking about the garbage barge. Captained by seasoned sailor Duffy St. Pierre, the tugboat Break of Dawn had dragged the Mobro 4000 barge, full of more than 3,100 tons of garbage, 6,000 miles along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, all the way to Belize. Everywhere St. Pierre went, the load of trash was rejected. Everywhere he went, he was told to move on.

It was the garbage no one wanted.

Generated in part in Islip, a town on Long Island's south shore, the trash seemed pretty innocuous.

"It wasn't even garbage; it was trash ... refrigerators and cardboard boxes and you-name-it," remembered St. Pierre in a 2010 interview on the radio series Action Speaks.

Trash hauler Lowell Harrelson, the owner of the Mobro 4000 garbage barge, had made a deal to offload the trash in North Carolina, where it would be used in a gas conversion project. St. Pierre was charged with getting it there.

"We had the intention – I did – of leveraging my position and the ownership and access to landfills into creating some methane gas production," Harrelson told Action Speaks.

Harrelson's idea was to collect the methane gas generated by the garbage and turn it into energy.

"That's all I want in this whole darn world – just 35 acres to try out my idea," a frustrated Harrelson told The New York Times in May 1987, 45 days in to the barge's embarrassing odyssey.

The problem came when St. Pierre tried to enter the harbor at Morehead City, N.C. Concerned the garbage contained hazardous materials, North Carolina officials refused to let St. Pierre offload the trash. St. Pierre and his crew stayed there 12 days, pelted with rotten eggs by unhappy residents, he said in the interview.

"They chased us out, and we headed toward Louisiana, went to Venice, and they made us get out," he remembered.

St. Pierre kept hauling the garbage, growing ever more smelly and fly-infested, to Alabama, Mississippi, Louisana, Texas, Florida and the countries of Mexico, Belize and the Bahamas, according to an Associated Press report from the time. The Mobro 4000 was rejected at each stop, a floating pariah.

"By that time, we had so much bad publicity; they were saying Jimmy Hoffa was buried in the barge, and it was carrying nuclear waste, and you-name-it, so they didn't want it. They wanted us to get out," St. Pierre remembered.

St. Pierre brought the Mobro 4000 back to New York, only to be rejected once again by the very state that had generated the garbage. He dropped anchor by New York June 17, according to the AP report. With nowhere to put the garbage, St. Pierre spent the summer with the Mobro 4000.

"They were going to put me in jail for five years if I left the barge unattended," St. Pierre said in the Action Speaks interview.

By that time, the "barge to nowhere" was a national joke, splashed across headlines and television news programs. The New York Times called it a "floating hot potato"; Time Magazine compared it to the Flying Dutchman, a mythical ship cursed to sail forever, never making port.

Vito Turso remembers when the Mobro 4000 was nightly fodder for Johnny Carson on his late-night talk show "The Tonight Show."

Turso, deputy commissioner for public information and community affairs for the New York City Department of Sanitation, was on hand when the garbage barge dilemma was finally resolved.

Negotiations that included the Department of Sanitation, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the town of Islip ended in a state judge approving a plan to incinerate the waste in Brooklyn.

The trash, determined to be non-hazardous, was burned in the fall of 1987. The ash residue was sent back to Islip, where a portion of the waste had originated, and buried. St. Pierre, now a national celebrity, was free of the garbage for good.

But the story of the wandering Mobro 4000 lingered in the public conscious. It was harshly evident that people couldn't continue sending all of their garbage to the landfill.

"Barge to nowhere made people more waste conscious and triggered more calls for recycling waste rather than throwing [it] away," Turso wrote.

Now, 25 years after the end of the Mobro 4000's journey, recycling and waste conversion programs are widespread and growing more popular every year.

The Mobro 4000 saga even inspired a 2010 picture book, "Here Comes the Garbage Barge," that adds some charming humor to the tale. With art made with recycled and found items, it's a fitting tribute to the garbage barge and its unfortunate cargo, all baled up with no place to go.

Contact Waste & Recycling News reporter Kerri Jansen at kjansen@wasterecyclingnews.com or 313-446-6098.