A Seminole Perspective on Ponce de León and Florida History

I always had a thirst, a hunger, for the history of my people. But when I was growing up, nobody talked much about it. There wasn’t time for much besides survival. We lived in chickees on the Brighton Seminole Reservation. My family was dirt poor and spent most of our time working in the fields, working with cattle, anything we could find, even cutting palm fronds for the Catholics to use on Palm Sunday. As a kid, I would hear my uncles talk about when the Seminoles all lived in camps across Florida and how they missed the free hunting and trapping way of life. When they came onto the reservation, it was like a death sentence to them. A lot of them became migrant workers just to keep food on the table. The struggle to survive overshadowed the memories of the shooting and guns and wars and genocide of the past.

When I was a boy, I also spent time in the world outside of the reservation. At the age of 3, I caught polio, and they took me away for three years in a crippled children’s hospital in Orlando. I remember when I finally came back. The first night I woke up in a chickee, I could smell the hog pens. I realized then that God had pity on me to put me on an Indian reservation, because nothing was going to come to me; I had to get off my ass and run it down myself. By seven I had thrown my braces into a cabbage tree. I played four years of high school football at Okeechobee High, rode bulls, went out with the pretty girls. I was determined to make it. If there was ever any prejudice directed at me, I didn’t know it.

As I got older, my hunger to learn about my people’s history only got stronger. I started doing a lot of independent research. I asked questions. People would tell me stories passed down, but I knew there was more. The more I studied, the more I didn’t understand the magnitude of what took place among my people. As time went on, I found out that other tribal members really wanted to know the history, too. My phone would ring off the hook with others wanting me to find out historical information for them. Long ago, they began calling me a tribal historian. I’ve got a history degree. I’ve amassed a large library of books written about my people, from every angle you can imagine. The past is very, very real to me. I am worried it could disappear unless we make a determined effort to preserve our history.

Last year I signed on as the Seminole Tribe’s representative in the Viva Florida 500 project [commemorating the 500th anniversary of Spanish explorers landing on Florida’s shore]. I didn’t do this to make a politically correct statement that will render everybody happy. I did it to make sure that the history of my people is represented. We are here to educate, not forgive. We are here to enlighten, not accuse. We want to keep very alive the memories of those days when the Europeans first came. We want to tell who the Spanish people were who came to our shores, and we want to educate people about exactly what they did. (Related story: "Florida Celebrates 500 Years After Ponce de León, But Why?")

People may not realize how many tribes and Native peoples existed before being decimated by the disease and warfare brought on by the Conquistadors. With the priests looking on, Spanish explorers took out the aboriginal Floridians with massacres in the name of God. And they sent the good news back to the King! But we can only speak for ourselves. The Florida Indians of long ago could illustrate what happened, but they didn’t write books and journals.

Indians all across America shared stories that were kept alive and passed down through the generations about what the European invaders did. That’s how it was told to me: The truth of those days was kill the Indian—or give him a blanket, invite him to supper, sneeze on his blanket, then send him away.

Yet we survived all of this atrocity. We actually learned from our attackers. We learned to practice slavery from them, and we even learned the behavior to sell out our own people. Creek warriors did real well in that regard; they would come down here and hunt down the other Indians the same way the white man did. They would sell Indians as slaves just like the white man did.

The Spanish brought in their culture and tried to make us a part of it. They were actually merciful in some ways. After they put you in your place, enslaved and unarmed, they would Christianize you and make you a Catholic. Our cultures clashed, and the Spanish had the upper hand.

When I think of the past, I feel like we were always running. For hundreds of years, we were on the run. We ran here from all over. Some of us ran here earlier than others. We Seminoles believe we are descended from the indigenous tribes of Florida, running and hiding like all the others. You had the Calusa, the Apalachicola, the Mayaimi along Lake Okeechobee, the Ais people of the Indian River Lagoon, the Tocobaga in Tampa, Arawak in the Caribbean, Timucua up in the northeast and the Tequesta in the southeast. The individual tribes were too small to engage in effective warfare with the Spanish and their allies. So they ran.

The Seminole Tribe of Florida has a Tribal Historic Preservation Department that is absolutely concerned with the accurate interpretation and preservation of our history—all the way back to the first peoples who occupied this land. Both the State of Florida and the United States, under the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), recognize the Seminole Tribe as the guardian of the ancient southeastern tribes who were eliminated from their homelands. It becomes our official duty to handle repatriations, which can include reburials of human remains and the return of funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. We have been involved in many, many of these cases.

While all Seminole people have respect for our culture and our ancestors, not all Seminoles agree on how we should relate with our neighbors. Some who have been quite active and vocal about these issues are Independent Seminoles who choose not to be enrolled members of the organized Seminole Tribe of Florida. They frequently speak at public meetings when issues arise where they perceive traditional Seminole culture is being wronged. Some of the Independents want to regain Paradise by loading every person in the state on a boat and then shipping ‘em all out. But that ain’t gonna happen.

I think education is the answer. Some Independents argue that the City of St. Augustine should tear down the old fort (Castillo de San Marcos) because of the atrocities that occurred to Indians there 400 years ago. I look at it differently. I would rather it remain standing so the memories of those days would not fade away. Those who don’t remember the past are doomed to repeat it.

For St. Augustine’s 450th anniversary (planned for 2015), I made a suggestion that it would be cool if we could invite representatives of all the Native tribes who were incarcerated there during and after the Seminole Wars, get them all together, and do a healing ceremony. But some Independents did not agree, so the Tribe refused to endorse the idea.

Many Seminoles would say: “Leave it all alone.” They argue we shouldn’t spend a whole lot of time, money, and effort on worrying about the Spanish conquistadors—that today there are much bigger things we need to be worried about.

Maybe the best place to focus on the history is in the schools. I don’t think the European invasion is discussed a lot in the classrooms. The conquistadors came over here 300 years before Andrew Jackson started chasing us. Students are taught more about the three Seminole Wars than the genocide performed by the Europeans and the Americans. In my home of Brighton, our charter school spends a lot of time on language, which is very important to us, and on taking the kids on cultural outings. The Spanish are part of the curriculum, but I don’t believe there is much said about it. We have to change that, in all Florida schools.

It’s too bad we all haven’t been talking about all this history all along. Maybe it would not have been so glorified.

In the end, I don’t believe the Spanish were ever that happy with Florida. We just didn’t have what they were looking so desperately for. They were basically gone by the Revolutionary War. Then along came the American settlers. Wouldn’t you know it, they wanted the Indians’ land. They held their meetings. “How we gonna get the land? What are we gonna do with the Indians?” Somewhere, someone had an idea: “Let’s hire Andy Jackson. He knows what to do: Write up failing treaties, spank ‘em in a few wars, go after ‘em, keep ‘em on the run, put ‘em out West somewhere.”

When the Supreme Court ruled the Indian Removal Act was unconstitutional, ol’ Andy Jackson just said “Stop me,” and rode off after the Indians anyway. If he defied the law like that today, the federal marshals would be all over him. To tell you the truth, Seminoles today despise Andrew Jackson more than the conquistadors.

But, you know how they say, “Out of bad things, good things come”? When the Spanish sailed away, they left their horses and cattle here, and we used them to start the Seminole cattle industry.

In fact, for most of the past 100 years in Florida, the Seminoles have thrived in the cattle industry. We once sold the meat and hides to the Cubans, even loaded up cattle on the St. John’s River. People called us the Cow Creeks. Today, we are the fourth-largest calf producers in the country! After we stopped running, those abandoned cattle pulled us through. That was our first casino: the Spanish cow.

If it was Paradise before the Europeans came, Florida was an absolutely horrible place to live after they left. Post-Civil War, you had outlaws, bandits, deserters, every sort of bad individual, all the problems of poverty, everyone hit hard. Before we got reservations we were surviving in little camps all over the Everglades and Big Cypress Swamp where only the mosquitoes and gators were supposed to be. Our homeland had shrunk. But we weren’t running anymore.

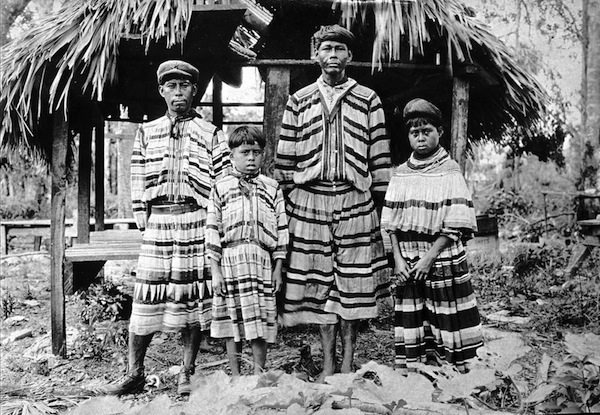

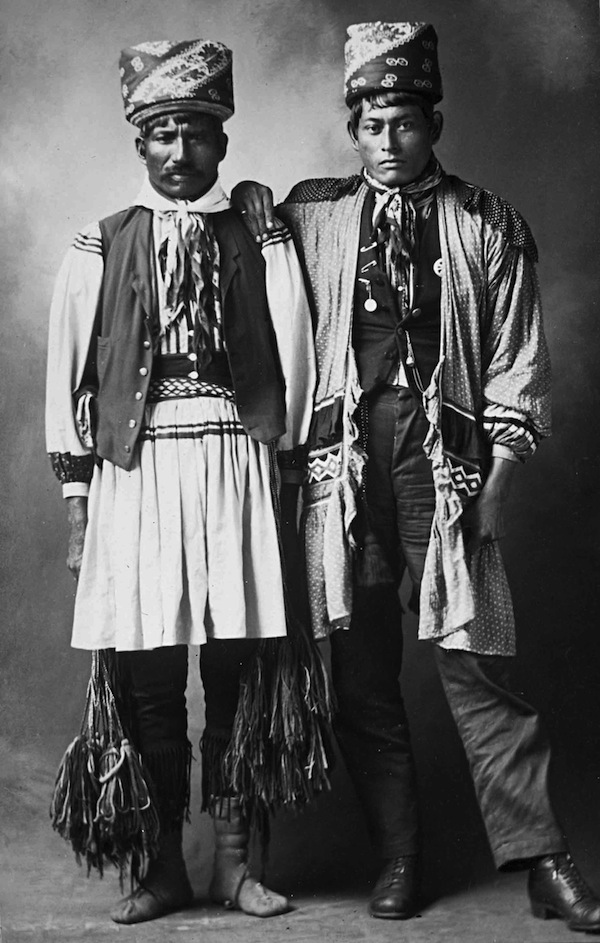

Our communities began to grow and we began to organize. The Indians who settled in the ‘glades became the Miccosukee and Big Cypress Seminoles. Those who lived to the North were Creek speakers whose descendents are the Brighton Seminoles of today. We survived nearly 500 years of genocide and atrocity with our culture and languages still intact. That is who we are.

The conquistador is a distant ghost. But we will not forget.

This article is reprinted from FORUM, the statewide magazine of the nonprofit Florida Humanities Council, which explores the heritage, traditions, and stories of our state.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/04/08/seminole-perspective-ponce-de-leon-and-florida-history-148672