Earth Magnetic Weather Message

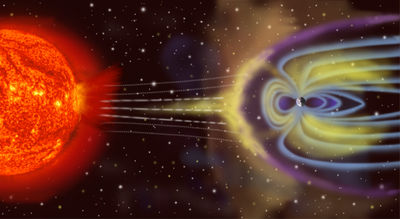

Earth's magnetic field (also known as the geomagnetic field) is the magnetic field that extends from the Earth's inner core to where it meets the solar wind, a stream of energetic particles emanating from the Sun. Its magnitude at the Earth's surface ranges from 25 to 65 µT (0.25 to 0.65 G). It is approximately the field of a magnetic dipole tilted at an angle of 11 degrees with respect to the rotational axis—as if there were a bar magnet placed at that angle at the center of the Earth. However, unlike the field of a bar magnet, Earth's field changes over time because it is generated by the motion of molten iron alloys in the Earth's outer core (the geodynamo).

The Magnetic North Pole wanders, but slowly enough that a simple compass remains useful for navigation. At random intervals (averaging several hundred thousand years) the Earth's field reverses (the north and south geomagnetic poles change places with each other). These reversals leave a record in rocks that allow paleomagnetists to calculate past motions of continents and ocean floors as a result of plate tectonics.

The region above the ionosphere, and extending several tens of thousands of kilometers into space, is called the magnetosphere. This region protects the Earth from cosmic rays that would strip away the upper atmosphere, including the ozone layer that protects the earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation.

Some of the charged particles from the solar wind are trapped in the Van Allen radiation belt. A smaller number of particles from the solar wind manage to travel, as though on an electromagnetic energy transmission line, to the Earth's upper atmosphere and ionosphere in the auroral zones. The only time the solar wind is observable on the Earth is when it is strong enough to produce phenomena such as the aurora and geomagnetic storms. Bright auroras strongly heat the ionosphere, causing its plasma to expand into the magnetosphere, increasing the size of the plasma geosphere, and causing escape of atmospheric matter into the solar wind. Geomagnetic storms result when the pressure of plasmas contained inside the magnetosphere is sufficiently large to inflate and thereby distort the geomagnetic field.

The solar wind is responsible for the overall shape of Earth's magnetosphere, and fluctuations in its speed, density, direction, and entrained magnetic field strongly affect Earth's local space environment. For example, the levels of ionizing radiation and radio interference can vary by factors of hundreds to thousands; and the shape and location of the magnetopause and bow shock wave upstream of it can change by several Earth radii, exposing geosynchronous satellites to the direct solar wind. These phenomena are collectively called space weather. The mechanism of atmospheric stripping is caused by gas being caught in bubbles of magnetic field, which are ripped off by solar winds.[17] Variations in the magnetic field strength have been correlated to rainfall variation within the tropics.[18]

Geomagnetic Sudden Impulse

Observed: 2013 Apr 13 2255 UTC

Deviation: 29 nT

Station: Boulder