Editor's Note: This story appears in our commemorative issue, "40 Years of Curbside Recycling."

There were many pioneers who pushed recycling forward. Here is a small sample of those who helped advance the movement.

Col. George Waring

Col.

George Waring

Col.

George Waring It's tough to imagine that there was a time, as recent as during some of our grandparents' lives, that our nation's cities were places of unimaginable filth.

New York was among the worst. Trash was dumped out windows, ash and dust covered everything, animal carcasses were left to rot on muddy city streets and the manure from the city's approximately 130,000 horses … ugh. (One visitor famously described the city as a "nasal disaster, where some streets smell like bad eggs dissolved in ammonia.")

George E. Waring Jr. became head of the New York's Department of Street Cleaning in 1895 and instituted a waste management reform plan that was nothing short of a miracle.

His disciplined, organized and hard-working "white wings" (he made them wear white uniforms and helmets) transformed the city's fetid streets into livable, clean spaces.

Part of Waring's plan was mandated recycling.

Waste was separated into three categories: rubbish (from which paper and rags were recovered), ash and "wet garbage" (or food waste). That wet trash, along with dead animals, was converted, through a process known as "reduction," into grease and fertilizer. The grease was used to make soaps, candles, lubricants, perfume and glycerine.

It would not be a stretch to call Waring both the father of modern waste management and the founding father of recycling.

"His broom saved more lives in the crowded tenements than a squad of doctors," wrote journalist and social reformer Jacob Riis. "It did more: It swept the cobwebs out of our civic brain and conscience."

Cliff Humphrey

Cliff Humphrey

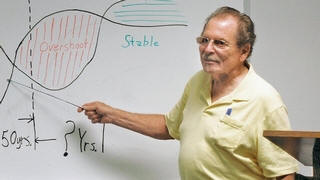

Cliff Humphrey At the 1988 National Recycling Congress in Minnesota, Cliff Humphrey was introduced to attendees as "the grandfather of recycling."

And like any grandpa, he's got some great stories.

Like back in 1969 in Berkeley, Calif., when he and his wife smashed their car with a sledgehammer and buried the engine in a coffin in a mock funeral ceremony attended by hundreds. News of the event appeared in newspapers across the country. It was part of a Smog Free Locomotion Day he had organized. The event became an annual demonstration against air pollution, with residents taking to the streets on bicycles, roller skates, shopping carts, even pogo sticks.

Or the time he appeared on the cover of the "New York Times Magazine" pushing a baby stroller during a parade on Earth Day 1970. Inside the buggy sat a bandaged globe.

Or the time he led dozens of friends and supporters on a Survival Walk to Sacramento, setting up one recycling center every day during their six-week trek.

The period was ripe for an environmental revolution, says Humphrey, who's now living in Kansas City, Mo.

"There was a certain anxiety to change things, to start fresh," he says, "and recycling just popped up."

In 1968, after rescuing hundreds of old bicycles and bike parts from the trash and holding a free bike swap in a city park, Humphrey had the idea to further reduce trash by setting up a trailer for residents to bring their old newspapers. Many believe it was the first modern-day recycling drop-off center in America.

The national media, in Berkeley covering the growing anti-war protests on campus, saw Humphrey and the Ecology Action group he helped create as a welcome relief for coverage.

"We weren't angry. We focused on the positive," Humphrey said. "We just seemed to fall into a scene of positive good news as a new front for journalists covering the Vietnam protests in Berkeley. It was kind of a wonderful thing."

Berkeley's recycling center quickly expanded to take in glass and cans. Soon, other drop-off centers popped up around the country: Baltimore, Ann Arbor, Mich., Chicago. By 1973, there were more than 300 nationwide. By then, a more efficient system of recycling — curbside collection — was starting to take off.

Humphrey is now 76, yet he is only semi-retired. He's writing books and helping increase multi-family recycling in Kansas City.

"I think we can achieve 80%," he says about the nation's recycling rate. "We climbed a hill, and there's a mountain to go."

Penny Hansen

The recycling movement has hundreds, if not thousands, of pioneers, the passionate people who set up recycling centers, organized early curbside programs, coordinated volunteers, pushed local governments to participate, figured out what practices worked best and formed crucial partnerships with haulers, cities and metal, glass and paper companies.

But perhaps only one pioneer did all of that.

After helping set up what's believed to be the first modern-day recycling drop-off center east of the Mississippi, in Baltimore in the late 1960s, Patty Hansen joined the fledging Environmental Protection Agency in 1972 as the agency's first recycling professional.

She quickly broadened her focus.

"Penny was an incredible advocate for recycling," remembers Chaz Miller, director of state programs at the National Solid Wastes Management Association and a colleague of hers at EPA in the 1970s. "And because of her experiences doing a recycling center, she wanted something more institutionalized, something more permanent, and something not reliant on volunteers."

That something was recycling at the curb, as part of regular waste collection programs.

"The goal was to make it part of the system," says Hansen, who still lives near Washington, D.C. "Not make it just do-gooders who were off doing what I did originally, which was having dumpsters in high school parking lots. The idea was to get it thoroughly integrated in that community."

During the 1970s, Hansen helped create literally hundreds of municipal recycling programs nationwide, traveling the country, working with cities, meeting with haulers and processors, offering technical assistance. She became a sort of the Penny Appleseed, planting recycling seeds nationwide.

Early on, in 1976, she launched two side-by-side pilot recycling programs, one in working-class Somerville, Mass., and one in the more affluent city of Marblehead.

"The thought was, 'only the elite will do these kinds of things,' " she remembers. "Could we get urban and suburban populations to participate?"

The results? Folks wanted to recycle.

"If you made it easy for people," Hansen says. "If they just had to put their stuff out next to their trash, they would happily comply."

The 'garbage barge'

Courtesy, Vito Turso Vito Turso of

the New York City Department of Sanitation, right, and

then-Sanitation Commissioner Brendan Sexton stand in front of

bales of Mobro 4000 waste.

Courtesy, Vito Turso Vito Turso of

the New York City Department of Sanitation, right, and

then-Sanitation Commissioner Brendan Sexton stand in front of

bales of Mobro 4000 waste. The Mobro 4000 barge departed a pier on New York's Long Island on March 22, 1987, piled high with bales of trash generated in part in Islip, a town on Long Island's south shore.

Towed by the tugboat Break of Dawn, the Mobro 4000 was meant to deliver its cargo to a landfill gas project in North Carolina.

But the barge's contents never made it to that its destination. When seasoned sailor Duffy St. Pierre tried to enter the harbor at Morehead City, N.C., state officials, concerned the garbage contained hazardous materials, refused to let him off load the trash.

St. Pierre got the same reception in Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Texas, Florida and the countries of Mexico, Belize and the Bahamas. The barge was rejected at each stop, a floating pariah.

After a 6,000-mile unsuccessful journey, St. Pierre brought the Mobro 4000 and its more than 3,100 tons of garbage back to New York City in June of 1987, only to be rejected once again by the very state that had generated the garbage. With nowhere to put the garbage, and threatened with jail time if he left the barge, St. Pierre spent the summer with the Mobro 4000.

By that time, the "barge to nowhere" was a national joke, and St. Pierre an accidental celebrity.

Finally, negotiations that included the Department of Sanitation, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the town of Islip ended in a state judge approving a plan to incinerate the waste, determined to be non-hazardous, in Brooklyn. The trash was burned in fall of 1987 and the ash residue sent back to Islip to be buried.

The story of the wandering Mobro 4000 made it harshly evident that people couldn't continue sending all of their garbage to the landfill. The homeless garbage barge became a smelly, fly-infested mascot for the movement toward more recycling.

![]()

w w w . w a s t e r e c y c l i n g n e w s . c o m

copyright 2013 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved.