Exploring the 'Science' Behind the Poll Snyder Cites to Defend His Redsk*ns

In a recent letter to Washington football fans, franchise owner and media mogul Dan Snyder offered tender reminiscences of the moments he and his father shared when they attended games at RFK Stadium. The recollections of a six year old boy holding his father’s hand, savoring the exuberance of life joined in communion with thousands of others from the neighborhood cheering their own on to victory, resonate for many who have had similar experiences with their own family members. Poignantly, he wrote “The past isn’t just where we came from – it’s who we are.”

In defense of the racial epithet that has spawned references to the team as the Washington Redsk*ns, an epithet that has been used to market one of the most lucrative franchises in NFL history with a value estimated at copy.8B with $381 million in revenue in 2012, Snyder wrote of the meaning of term. Snyder asserted that, “It is a symbol of everything we stand for: strength, courage, pride, and respect -- the same values we know guide Native Americans and which are embedded throughout their rich history as the original Americans.”

RELATED: Man Who Ran Dan Snyder's Poll: 'Of Course I'd Change the Name!'

In support of his contention of the positive meaning ascribed to a term identified in dictionary definitions as racially offensive and believed to be as racially charged as the n-word, he cited an Annenberg Public Policy Center survey that reportedly found among self-identified Native Americans, 90 percent did not consider the term offensive.

Artfully, Mr. Snyder’s letter achieves two things. First, he conveys the message that he means no harm in insisting on using and profiting from the term. And second, American Indians are effectively not harmed for the most part because they do not take offense, ignoring of course the inconvenience of the minority nine percent who were (one percent not responding).

The “science” of the Annenberg survey result provides ammunition, as it were, to reinforce a position that neither harm is intended nor does it exist. There is something interesting, however, in the juxtaposition of the two. While Snyder speaks for himself, the “scientific fact” of the Annenberg finding replaces the “voice” of American Indians.

This is significant when one lifts the curtain to examine how the “science” was conducted. While the popular media represent the finding as emanating from the Annenberg Public Policy Center, or as Snyder noted in his letter, as the “highly respected Annenberg Public Policy Center,” reference to the fact that the question posed was part of the 2004 National Annenberg Election Survey (NAES04) is rarely if ever noted. And it should be.

Reasonably, an inquiring mind ought to wonder how a question regarding the Washington football franchise ended up in a survey whose sole design was to track the dynamics of the opinions of the electorate over the course of the 2004 presidential campaign. The express purpose of the survey was an examination of “a wide range of political attitudes about candidates, issues and the traits Americans want in a President.”

Search through the 638-page NAES04 National Rolling Cross-Section Codebook, and the 837-item questionnaire, and you will find this question directed only to Native Americans, a question which was not part of the U.S. presidential campaign that year, or any other year. Until this item was included in the survey, the opinions of American Indians in the survey were not tracked. The first iteration of the NAES in 2000 made no attempt to recognize American Indians as respondents.

There were substantive American Indian issues that were a part of the presidential campaign in 2004. The Republican Party Platform, for example, included a full section on Native Americans, stating

The federal government has a special responsibility, ethical and legal, to make the American dream accessible to Native Americans. Unfortunately, the resources that the United States holds in trust for them, financial and otherwise, have been misused and abused. While many tribes have become energetic participants in the mainstream of American life, the serious social ills afflicting some reservations have been worsened by decades of mismanagement from Washington.

An acknowledgement of the U.S. government’s failure to fulfill its trust obligations to American Indians well deserved a question in the survey, not just for American Indians but for all respondents.

And thus we return to the “science.” Interviewed after the release of the finding in September of 2004, Adam Clymer, the director of the NAES04 explained, “Every year there would be some degree of controversy over the name…” As indisputable as that observation is, the design of the NAES04 was to reflect a non-partisan stance on the part of the researchers. Items in the survey were not selected merely as a matter of convenience because they had lingered in the public domain without resolution for years. They were included because they had a direct connection to the stated purpose of the survey. One would think that a true measure of opinion on this issue in communities as diverse as Indian nations would take many factors and questions into account, and merit more than just a follow-up question tacked on to a political survey of the general American population.

Compared to the other questions in the survey, this one stands out not only because it falls outside of the bounds of the presidential campaign. It also stands out in terms of construction. Consider the comparison below.

|

Example of Campaign Question |

Question Re: the Washington R-Word |

|

Thinking about the promises George W. Bush made as a candidate, in your opinion, has he kept all, most, some, few, or none of his promises? |

The professional football team in Washington calls itself the Washington Redsk*ns. As a Native American, do you find that name offensive, or doesn’t it bother you? |

While the question regarding George Bush conforms to research protocol, the one about the Washington team breaks a basic design principle by presenting respondents with two different questions in one. The first is a clear and concise question. The second effectively renders responses invalid because the response choices do not measure the same thing. This departure in form is noticeable not just in the comparison of these two questions but in the comparison of the question re: the Washington team and all other questions in the survey.

There is also the matter of the number of individuals who are believed to have responded to the survey question. According to the press release issued by APPC about the Washington finding, 768 were to have responded to the question. However, in a book entitled Capturing Campaign Dynamics 2000 & 2004 by those who worked on the NAES, the number of Native Americans was reported to be 1010. If that is the case, and if the question regarding the Washington team was posed to them, then nearly 25 percent of responses were not accounted for in the press release.

These irregularities are compounded by the failure in the design or interpretation to recognize the definitional complexities of identifying an American Indian respondent pool. Social scientists have long held that treating American Indians as a singular homogeneous group does not account for the regional, linguistic, and cultural diversity that exists across the more than 550 American Indian nations. Nor does it capture the consequences of the legacy of forced assimilation where the strength of identity can vary greatly among the American Indian population, with some identifying strongly as American Indians and others identifying strongly as Americans with still others identifying somewhere across the spectrum. Those variations affect the reading of the data and call into question whether the sample was truly representative from the start. Nor does it take into account the digital divide that exists in Indian country. At the time the survey was started in 2003, more than 30 percent of American Indian homes located on reservations and on off-reservation trust lands would not have had phones, a reality that challenges the presumption that possible respondents had an equal shot at being included in survey.

The position of the APPC in relationship to the public dialogue regarding the Washington team is revealed in an October 10, 2013 press release, issued nine years after the survey was completed. The press release reported that renewed controversy on the issue resulted in the 2004 finding being cited in the news. The decision to specifically highlight that Dan Snyder had used the information as “key evidence in support of the name” in that press release is revealing. While links to other news accounts were posted at the bottom, it is the Snyder letter that is featured in the release.

Anthony Tyeeme Clark characterizes this kind of flawed science as “the lingering residue of colonization.” Tracing its circulation through the mass media, the “fact” that American Indians are not offended by the r-word takes flight, moving through “media communications into local politics, which in turn function to transform not only our images but our voices as well.”

That lingering residue of colonization and the transformation of American Indian voices is seen not only in the editorial decision to feature the Snyder letter to fans in the APPC press release but the editorial decision as to what was not included in the article links. An article that was missing from the list written by ESPN writer, Rick Reilly in mid-September of 2013 had generated considerable attention. Like Snyder, Reilly too had sought to use the Annenberg fact to prove that American Indians were not offended by the Washington imagery. He wrote

And even though the Annenberg Public Policy Center poll found that 90 percent of Native Americans were not offended by the Redskins name, and even though linguists say the “redskins” word was first used by Native Americans themselves, and even though nobody on the Blackfeet side of my wife’s family has ever had someone insult them with the word “redskin”, it doesn’t matter. There’s no stopping a wave of PC-ness when it gets rolling.

Significantly, Reilly’s assertion regarding his in-laws is a misrepresentation. His wife’s father, Bob Burns, a Blackfeet elder, sought a correction from Reilly, who reportedly refused. In order to set the record straight, Burns published an article in Indian Country Today Media Network, writing

I grew up seeing store signs in the nearby town of Cutbank that read “No dogs or Indians” allowed…I could never support the term ‘redskins’ because we know first-hand what racism and ignorance has done to the Blackfeet people. Our people grew up hearing terms like nits, dirty redskins, prairen-word, savages, heathens, lazy Indians and drunks – all derogatory terms used to label us. It is better today, but the underlying mentality is still there or obviously people would change the name.

Snyder is correct in his assertion that the past isn’t just where we came from – it’s who we are. To illustrate, the APPC’s position of neutrality obscures the intersections that exist between its home institution, the University of Pennsylvania and the NFL, which run long and deep. Bert Bell, co-founder and co-owner of the Philadelphia Eagles and eventual commissioner of the NFL, was a student at Penn, quarterbacking the 1916 team that played in the Rose Bowl. Lud Wray, a teammate of Bell’s and his business partner in the Eagles venture, started his career as a professional football coach in 1932 with the Boston Braves, the team that owner George Preston Marshall would rename the following year as the Redsk*ns. Walter Annenberg , the man who built a vast media empire eventually sold to Rupert Murdoch (Fox Broadcasting, 21st Century Fox, and News Corps) and the benefactor for whom the public policy center is named, attended Penn’s Wharton School in 1931. Annenberg developed a close working relationship with Bell for a time. Penn’s stadium, Franklin Field, served as home to the Eagles from 1958 through 1970, a rent free arrangement given Penn’s not-for-profit status with all concessions and parking revenues along with a donation from the Eagles to pay for field maintenance and upkeep. And while Annenberg and Bell would have a falling out in 1948 that would never be mended, it is worth noting that current Eagles owner, Jeffrey Lurie, now lives in the Main Line mansion previously owned by Annenberg. Although Lurie would divorce his wife Christina, she remains involved with the Eagles franchise. In 2012, the then Mrs. Lurie donated $5,000 to the campaign of Republican candidate, Jon Huntsman, for whom the building which houses the Wharton School for Business on the Penn campus is named. The Wharton School runs the NFL-NFLPA Business Management and Entrepreneurship Program. Former Pennsylvania governor, Philadelphia mayor, and faculty member in the Fels Institute of Government at Penn, Ed Rendell, who is also a graduate of Penn, is a longstanding member of Comcast Sportsnet’s broadcast team covering the Eagles.

And while these intersections may not have overtly produced the question that appeared in the NAES04 survey about the Washington franchise, there is an institutional investment at some level in the question itself and the outcome. And that institutional investment is complicated. In 1996, long before the APPC chose to include the question at issue in the NAES04, Director of Wharton’s NFL-NFLPA Business Management and Entrepreneurship Program, Kenneth Shropshire, described the casual racism that the Washington Redsk*ns represents in his book entitled In Black and White: Race and Sports in America. Characterizing sport as a “sanctuary” where racialized ways of thinking allowed sport executives and the masses to routinely engage in racist behavior, he wrote, “None is quite so glaring as the Washington Redsk*ins football team.”

The past isn’t just where we came from – it’s who we are. The insistent use of a racially offensive epithet in the marketing of a professional sport franchise for the purpose of profit is a haunting reminder of how the past becomes internalized and carried forward to the present. Sustained by money and power, the misappropriation of American Indian imagery is reflective of how American Indians continue to be treated in the society more generally.

Psychologist Stephanie Fryberg has documented that the use of American Indian stereotypes by sport teams and in the entertainment industry harms American Indian children by diminishing their self-esteem and confidence while providing a boost in esteem to white children.

In the recently released Ending the Legacy of Racism in Sports & the Era of Harmful “Indian” Sports Mascots, the National Congress of the American Indian (NCAI) reminds us again that Native peoples remain more likely than any other race to experience crimes at the hands of a person from another race. Native youth experience the highest rates of suicide among young people. With studies showing that negative stereotypes and harmful “Indian” sports mascots are known to play a role in exacerbating racial inequity and perpetuating feelings of inadequacy among Native youth, it is vital that all institutions—including professional sports franchises re-evaluate their role in capitalizing on these stereotypes.

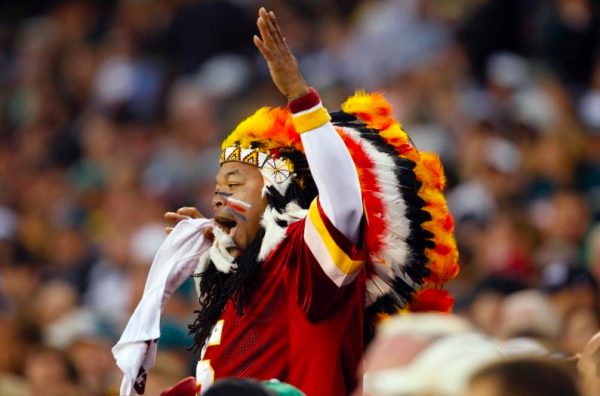

As a measure of privilege, the “scientific fact” that American Indians are not offended by the term “redskins” is woven into the stories of honor that non-Indians tell each other to justify the unjustifiable, hiding behind a wall of assumed objectivity. The notion that strength, courage, pride and respect of American Indians are the qualities recognized by fans of the Washington team is belied in their chosen representations.

A few weeks ago an incident involving African-American lineman Jonathan Martin on the Miami Dolphins who alleged that he had been bullied by White teammate and member of the players’ leadership council, Richie Incognito, drew national media attention. Incognito readily admitted to using the n-word in the locker room when speaking with other players. In response,

The Fritz Pollard Alliance, a group formed to promote diversity in the NFL, released a statement urging players not to use that kind of language with each other after game day officials reported what was described as “the disturbing trend of racial epithets, including the N-word”. The statement went on to emphasize that the use of the N-word simply could not be condoned at any level.

If racial epithets cannot be condoned at any level within the NFL then there is no place for the one that adorns the uniforms of the franchise in Washington. One “scientific” fact cannot change that.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/12/16/exploring-science-behind-poll-snyder-cites-defend-his-redskns-152739