Genetic

Changes to Food May Get Uniform Labeling

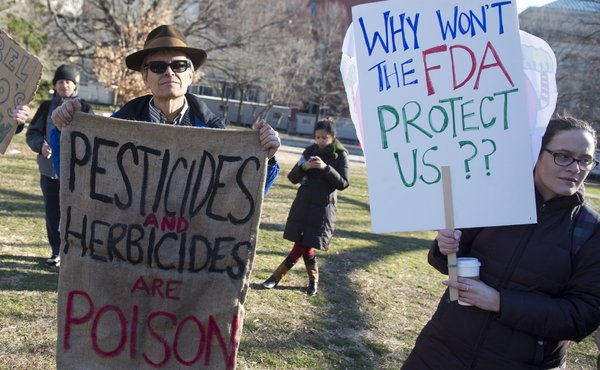

Opponents of genetically engineered food protested last month at Lafayette Park near the White House.

By STEPHANIE STROM

Published: January 31, 2013

With Washington State on the verge of a ballot initiative that would require labeling of some foods containing genetically engineered ingredients and other states considering similar measures, some of the major food companies and Wal-Mart, the country’s largest grocery store operator, have been discussing lobbying for a national labeling program.

Executives from PepsiCo, ConAgra and about 20 other major food companies, as well as Wal-Mart and advocacy groups that favor labeling, attended a meeting in January in Washington convened by the Meridian Institute, which organizes discussions of major issues. The inclusion of Wal-Mart has buoyed hopes among labeling advocates that the big food companies will shift away from tactics like those used to defeat Proposition 37 in California last fall, when corporations spent more than $40 million to oppose the labeling of genetically modified foods.

“They spent an awful lot of money in California — talk about a lack of return on investment,” said Gary Hirshberg, co-chairman of the Just Label It campaign, which advocates national labeling, and chairman of Stonyfield, an organic dairy company.

Instead of quelling the demand for labeling, the defeat of the California measure has spawned a ballot initiative in Washington State and legislative proposals in Connecticut, Vermont, New Mexico and Missouri, and a swelling consumer boycott of some organic or “natural” brands owned by major food companies.

Mr. Hirshberg, who attended the January meeting, said he knew of roughly 20 states considering labeling requirements.

“The big food companies found themselves in an uncomfortable position after Prop. 37, and they’re talking among themselves about alternatives to merely replaying that fight over and over again,” said Charles Benbrook, a research professor at Washington State University who attended the meeting.

“They spent a lot of money, got a lot of bad press that propelled the issue into the national debate and alienated some of their customer base, as well as raising issues with some trading partners,” said Mr. Benbrook, who does work on sustainable agriculture.

For more than a decade, almost all processed foods in the United States — like cereals, snacks and salad dressings — have contained ingredients from plants with DNA that has been manipulated in a laboratory. The Food and Drug Administration, other regulators and many scientists say these foods pose no danger. But as Americans ask more pointed questions about what they are eating, popular suspicions about the health and environmental effects of biotechnology are fueling a movement to require that food from genetically modified crops be labeled, if not eliminated.

Impending F.D.A. approval of a genetically modified salmon and the Agriculture Department’s consideration of genetically engineered apples have further intensified the debate.

“We’re at a point where, this summer, families could be sitting at their tables and wondering whether the salmon and sweet corn they’re about to eat has been genetically modified,” said Trudy Bialic, director of public affairs at PCC Natural Markets in Seattle. “The fish has really accelerated concerns.”

Mr. Hirshberg said some company representatives wanted to find ways to persuade the Food and Drug Administration to proceed with federal labeling.

“The F.D.A. is not only employing 20-year-old, and we think obsolete, standards for materiality, but there is a general tendency on the part of the F.D.A. to be resistant to change,” he said. “With an issue as polarized and politicized as this one, it’s going to take a broad-based coalition to crack through that barrier.”

Morgan Liscinsky, an F.D.A. spokeswoman, said the agency considered the “totality of all the data and relevant information” when forming policy guidance. “We’ve continued to evaluate data as it has become available over the last 20 years,” she said.

Neither Mr. Hirshberg nor Mr. Benbrook would identify other companies that participated in the talks, but others confirmed some of the companies represented. Caroline Starke, who represents the Meridian Institute, said she could not comment on a specific meeting or participants.

Proponents of labeling in Washington State have taken a somewhat different tack from those in California, arguing that the failure to label will hurt the state’s fisheries and apple and wheat farms. “It’s a bigger issue than just the right to know,” Ms. Bialic said. “It reaches deep into our state’s economy because of the impact this is going to have on international trade.”

A third of the apples grown in Washington State are exported, many of them to markets for high-value products around the Pacific Rim, where many countries require labeling. Apple, fish and wheat farmers in Washington State worry that those countries and others among the 62 nations that require some labeling of genetically modified foods will be much more wary of whole foods than of processed goods.

The Washington measure would not apply to meat or dairy products from animals fed genetically engineered feed, and it sharply limits the ability to collect damages for mislabeling.

Mr. Benbrook and consumer advocates say the federal agencies responsible for things like labeling have relied on research financed by companies that make genetically modified seeds.

“If there is a documented issue with this overseas, it could have a devastating impact on the U.S. food system and agriculture,” Mr. Benbrook said. “The F.D.A. isn’t going to get very far with international governments by saying Monsanto and Syngenta told us these foods are safe and we believed them.”

Advocacy groups also have denounced the appointment of Michael R. Taylor, a former executive at Monsanto, as the F.D.A.’s deputy commissioner for food and veterinary medicine.

Ms. Liscinsky of the F.D.A. said Mr. Taylor was recused from issues involving biotechnology.

What has excited proponents of labeling most is Wal-Mart’s participation in the meeting. The retailer came under fire from consumer advocates last summer for its decision to sell a variety of genetically engineered sweet corn created by Monsanto.

Because Wal-Mart is the largest grocery retailer, a move by the company to require suppliers to label products could be influential in developing a national labeling program.

“I can remember when the British retail federation got behind labeling there, that was when things really started to happen there,” said Ronnie Cummins, founder and national director of the Organic Consumers Association. “If Wal-Mart is at the table, that’s a big deal.”

Brands like Honest Tea, which is owned by Coca-Cola, have written to the association, which estimates 75 percent of grocery products contain a genetically modified ingredient, to protest its “Traitors Boycott,” which urges consumers not to buy products made by units of companies that fought Proposition 37. Consumers have peppered the companies’ Web sites, Facebook pages and Twitter streams with angry remarks.

Ben & Jerry’s, the ice cream company, announced recently that it would remove all genetically modified ingredients from its products by the end of this year. Consumers had expressed outrage over the money its parent, Unilever, contributed to defeat the California measure.

The state Legislature in Vermont, where Ben & Jerry’s is based, is considering a law that would require labeling, as is the General Assembly in Connecticut. Legislators in New Mexico have proposed an amendment to the state’s food law that would require companies to label genetically modified products.

And this month, a senator in Missouri, home of Monsanto, one of the biggest producers of genetically modified seeds, proposed legislation that would require the labeling of genetically engineered meat and fish.

“I don’t want to hinder any producer of genetically modified goods,” the senator, Jamilah Nasheed, who represents St. Louis, said in a news release. “However, I strongly feel that people have the right to know what they are putting into their bodies.”

© 2013 The New York Times Company