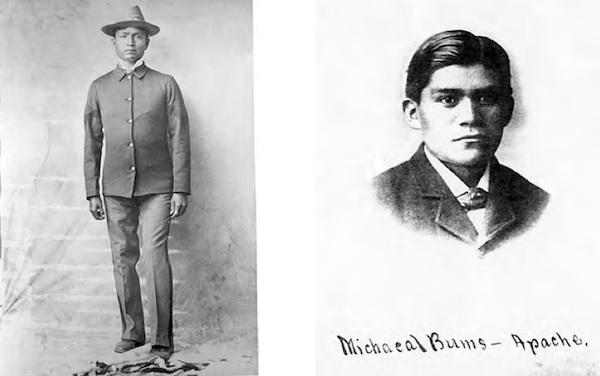

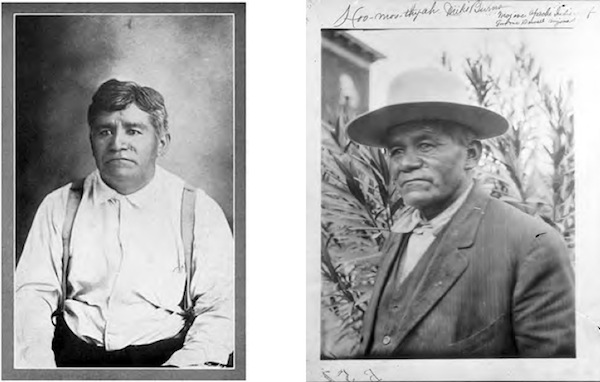

Editor's note: Hoomothya was a Yavapai Indian who as a boy witnessed the massacre of 225 fellow tribal members at the hands of American soldiers in what has come to be known as the Battle of the Caves. Taken in by Captain James Burns, the boy Hoomothya, or Wet Nose, spent his childhood crisscrossing Turtle Island with the soldiers, for the first few months with Burns, who called him Mike. The adult Mike Burns held various jobs throughout his life, including in the military. He tried often to have his memoirs published, but to no avail. They were finally picked up by the University of Arizona Press and edited by Gregory McNamee as The Only One Living to Tell: The Autobiography of a Yavapai Indian, published in 2012. Here are parts of his story.

--------------

I cannot say exactly when or where I was born, because I belonged to an Apache Indian family whose parents were not educated, so that I could not find any records of my birthplace. Only educated people keep records of their children so that they can know where they were born, and besides, there are no older Indians left alive now. All of my people were killed by the soldiers and by Indian scouts who worked for the government. This was in 1872, in a cave on the north side of the Salt River, where about 225 souls—men, women and poor innocent children—were living. The place is on the north side of the mouth of Fish Creek on the Salt River, where Horseshoe Dam is now.

It all happened on December 22, 1872, he tells us, a date recorded by one Lieutenant E.D. Thomas. Burns first recalls the murder of his mother, which predated the massacre.

It is a mysterious thing, the fact that I am alive to tell how I was saved, while every last one of my tribe was killed. I can only guess that I was born in 1864, because Lieutenant Thomas told me that on the day I was captured he reckoned me to be seven or eight years old. That would make me sixty-six years old now, though I know that I am older than that because I know many things from way back. I can remember when my mother was killed by soldiers a few miles east of Mormon Flat. She ran for her life and crawled into a rock hole, too, and she was pulled out and shot many times. I then had two children to take care of, a little brother and a baby sister. I remember that as if it had happened just a short time ago. It was an awful day for me after I lost my poor mother and had to look after two children. My aunt had a baby, and so that way my little sister was nursed.

From that time on my father had a bitter hatred for soldiers and all white people. My father and others would go down into the Salt River Valley looking for soldiers or white men to kill.

Burns happened to be traveling in the bush with his uncle when he was apprehended by the soldiers and dragged to the cave. Here, he recounts what happened after the soldiers grabbed him.

One soldier had me by the arm, just tumbling me over the bushes and the rocks. He didn’t care whether I was hurt or killed; he took me along just like he was dragging a log.

Most of the soldiers, about six hundred of them, were on a three-hundred-foot-tall cliff at the east corner of the cave. They could not see the Indians. [Chief] Delshe had said that no enemy would dare attack there because it was such a fortified place. The Indians thought that they were strongly protected, but then the soldiers shot down volleys, bucketsful of lead behind the big boulders against the walls of the cave, pouring down such showers of lead that those whom the bullets hit could not be recognized as humans. The war songs ceased. Only one man was left, and he had just one shot remaining, and with it he killed a Pima Indian scout, right at noon. He might have killed more, but when he reached out with his gun to drag over bullets or a bag of gunpowder, the soldiers fired, and their shots bent his gun nearly in two. He was helpless, and then he was finally shot. He was my brother-in-law, a man who never missed a shot, and he died like a man.

The Pima and Maricopa scouts rushed in and killed any Indians who were still alive. They pounded their heads in right in front of the soldiers. Some Apache scouts who were with the soldiers found some women and children alive, and they handed them over to the officers for fear that the Pimas and Maricopas would get them too, so enraged were they, even though just one of their number got killed that day.

They weren’t satisfied with killing more than two hundred men, women, and innocent children. They gathered about thirty of the wounded and killed them too.

Some Apache scouts had fired warning shots before the soldiers arrived. If Delshe’s band had rushed out of the cave when they heard them, they would not have been slaughtered. A few feeble old men and women might have been killed, but Chief Delshe urged everyone not to make a break for it. Most of the Indians were depending on the old chief because he had been a great warrior and had fought all kinds of people, and he had always come out victorious when he fought against soldiers and Pimas. This time he was pinned down and surrounded, and he could not protect his people.

After the last of the Yavapais were killed, I was led into the cave. I saw dead men and women lying around in all shapes, horrid to look on. I saw where my grandpa lay; I saw at a distance a body that was in a little rock hole, headfirst, and that was the old man. I was at the west entrance of the cave and sat there crying to death. Then I thought of my little brother and sister, the two I cared for and fed as a mother would. No more hope, no more kinfolk in the world. What would I do? Should I give myself up to the Pimas and Maricopas to be killed there with my family? Should I forget those awful deeds against my people and take on a new and manly courage, resolve to be a different man and hope for a better future?…

In all history no civilized race has murdered another as the American soldiers did my people in the year 1872. They slaughtered men, women, and children without mercy, as if they were not human. I am the only one living to tell what happened to my people.

After a few months, James Burns took ill and left for Washington. Mike Burns ended up in the care of Captain Hall S. Bishop, who took him in as something of a foster child. Burns spent the next several years crisscrossing Turtle Island with Bishop and the soldiers, the only family he had. Bishop was kind to him, though life was hard. The following account of a battle’s aftermath and other hardships illustrates how the harshness of life in this era intersected with the disingenuous psyche of a little boy.

I asked where my pony was, and Lieutenant Bishop said that a note had come from headquarters saying that all the ponies captured at the Slim Buttes Fight were to be slaughtered for issue as rations. I asked him to write me a note to get my pony back, and he wrote out a note and handed it to me, and I ran down to headquarters and found General Crook at home. He was very glad to see me, and he took both my hands in his and asked what the trouble was, so I handed him the note, and he read it, and then said, “It might be too late, my Apache boy. I am very sorry to take your only pony away from you, but I will do what I can to get it back to you, if possible.” So he handed me another note and told me to run to the quartermaster general, who would secure my pony. I went to the quartermaster general, who told me to look through the ponies and find mine. I couldn’t find him, and he told me that it must have been among the ponies that had already been killed, so there was nothing to be done about it now.

I almost cried when I heard that my pony had been killed. I would have to travel on foot for the rest of the campaign. The next morning we ate horsemeat for breakfast, and Lieutenant Bishop told me that I had to join the foot gang. Then he gave me a chunk of cooked horsemeat for lunch.

Copyright 2012, University of Arizona Press. Reprinted with permission

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/02/24/only-one-living-tell-excerpt-massacres-sole-survivor-finally-gets-his-day-print-147864

Comment

This story makes me sad. Reminds me of all the many murders of our many people from long ago & still yet today by evil people.

Just hearing the stories retold by the elders in times past is like reliving those events yesterday. The washichu tells their side to things, but seldom is OUR side heard of those same events in history.

When you are fortunate to hear those stories from our elders you see a whole different side to those stories I find. You see parts that were never told by the whites. You see how what our people have to share show what cowards those soldiers were. You see the outright lies revealed that made it to the newspapers of those days.

Ask OUR people about the same stories & you will find a whole new part come to life that shows our bravery, decency to others, kindness, the gentleness of our people, etc.

Our elders & keepers of oral histories are a treasure beyond measure. Show them the respect & honor they deserve. Without them, our past fades into the shadows & becomes a myth.