China's new leader: harbinger of reform or another conservative?

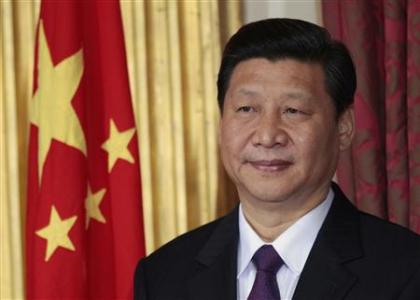

China's then Vice-President Xi Jinping stands during a trade agreement ceremony between the two countries at Dublin Castle in Dublin, Ireland in this February 19, 2012 file photo.

Credit: Reuters/David Moir/Files

BEIJING |

(Reuters) - When Xi Jinping became the new leader of China's Communist Party two months ago, hopes were high for reform in the giant nation. But despite what appears to be sensitive handling of a strike by journalists and a challenge to Beijing's tight control of the press, signs of change seem tentative.

Xi's commitment to reform, or lack of it, will come into sharper focus over the next few months, in particular after he officially assumes the presidency in March at a session of the National People's Congress, the country's rubber-stamp parliament.

Among the key signposts that analysts say could give Chinese citizens and global investors a sense of the new government's commitment to change: whether the resolution of a standoff at a prominent newspaper leads to an easing of press restrictions; whether the government moves quickly to address the rights of China's migrant workers; and whether Xi follows through on ending the country's notorious "re-education through labor" camps.

Xi himself has fanned expectations of change with rhetoric about "national rejuvenation," vows to crack down on corruption and a down-to-earth public style that stands in contrast to the remote, forbidding demeanor of his predecessors.

From a trip to Guangdong province akin to Deng Xiaoping's famous "southern tour" in 1992 - which re-ignited China's economic opening - to a speech calling for the rule of law in mid-December on the 30th anniversary of China's constitution, Xi has kindled hopes that he might pursue a broad swath of reforms -- economic, legal and political.

"It is evident that the new leaders want to get things done and have done things differently from previous administrations," said a source with close ties to the leaders.

But to date, for all the ostensible desire for change, Xi and the new leaders have precious little to show for it. China has one of the most regimented political systems in the world, and the writ of the Communist Party remains supreme.

At the November party congress in which Xi and his team were officially unveiled, there was talk of reform. But maintaining stability was the over-arching theme.

Xi's defenders argue that expectations of swift, significant change are premature. His prime minister, Li Keqiang, doesn't officially form a government until the parliament session in March.

For now, ambiguity prevails. "In intellectual debate, both the left and the right, conservatives and liberals, think Xi Jinping will be on their side", says Cheng Li, a China expert at the Brookings Institution.

"But in half a year, or one year, I think one group will be disappointed."

Skeptics say there are few convincing signs of even impending change.

"There is a scent of this (reform). Everyone has detected the aroma. But if you ask, is there really rain? Is there really wind? I don't think so," said Chen Ziming, an independent political commentator in Beijing.

ONE GLIMMER

Resolving the strike at the Southern Weekly newspaper in Guangdong, one of China's most respected and liberal, provided a glimmer of reform even as it was clouded in uncertainty.

The protest was against Propaganda Ministry officials who allegedly rewrote an editorial the paper had prepared that called on the government to respect the rights of individuals under China's constitution into one that praised the party.

Sources told Reuters that after the intervention of new Guangdong party secretary Hu Chunhua, the situation was resolved with an agreement from the Propaganda Ministry that it would no longer censor the paper's articles before they are published.

Some analysts believe the decision is an isolated one and holds little long-term significance. But if the agreement holds, it will be a step toward loosening what has been a suffocating censorship regime.

It is unlikely Hu acted without at least the party Politburo's tacit awareness. To what extent, if any, the Southern Weekly episode might herald a somewhat more independent press will now be scrutinized intensely.

OTHER SIGNPOSTS

There are other potential areas for change.

One is the so called "hukou" household registration system, that effectively prevents millions of China's migrant workers and their families from receiving health care and schooling in the wealthier regions where they work. Such services are only provided to people in the areas where they were registered at the time of birth.

If the central government is serious about improving the rights of migrants - to which it has long given lip service - it will at the same time have to change the way local governments now finance themselves, which is currently mainly through land sales to real estate developers.

Without creating a broader and more consistent tax base, economists say local governments will not be able to afford the extra costs associated with real hukou reform.

If the central government begins to push provinces to move on local fiscal reform, it will likely be a signal that it also may eventually get serious about change to the hukou system.

Those changes will be complex. For that reason, if Xi and Li are "serious", said University of California San Diego economist Barry Naughton, "reform in this respect has to be started right now."

The new government already appears to be moving on China's notorious re-education through labor (RETL) system, which allows police to detain people for up to four years without an open trial, in contravention of China's constitution.

Meng Jianzhu, a former minister of public security in Beijing and now the head of the political and legal committee of the National People's Congress, said recently that the NPC seeks "the end of the use of RETL."

Human rights advocates are watching closely whether the government follows through and eliminates the "re-education" system.

As long as the re-education through labor system isn't replaced by something similar, said Sophie Richardson, China Director at Human Rights Watch, "the decision would be an indisputable step towards establishing the rule of law in China."

Taken together these are straws in the wind, "subtle changes but not a coincidence," said the source with ties to the leadership. Xi's goal may be to promote moderate change while maintaining stability.

"Stability still prevails over all else," the source said.

The trick now for Xi is making sure the changes the new leadership allows aren't so subtle that few feel them, but will not risk the stability that is paramount for them.

(Editing by Bill Powell and Raju Gopalakrishnan)

![]()

© Thomson Reuters 2012 All rights reserved