New

York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg. On June 11, the

mayor unveiled the world's most comprehensive

climate change adaptation plan. But scientists say

they're concerned that as global warming intensifies

amid the lack of progress on curbing global carbon

emissions, even this plan won't be enough for

long-term flood protection. Credit: The World Bank,

flickr

New

York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg. On June 11, the

mayor unveiled the world's most comprehensive

climate change adaptation plan. But scientists say

they're concerned that as global warming intensifies

amid the lack of progress on curbing global carbon

emissions, even this plan won't be enough for

long-term flood protection. Credit: The World Bank,

flickr Mayor Michael Bloomberg's plan to protect New York City from future superstorm Sandys and other climate-related threats is the most ambitious and scientifically accurate plan of its kind in the world. But as global warming intensifies and sea levels rise, even this strategy may not be enough to flood-proof the city for very long, experts say.

The climate adaptation plan, unveiled last week, would funnel $19.5 billion into more than 250 initiatives to reduce the city's vulnerability to coastal flooding and storm surge. It comes eight months after Sandy engulfed 1,000 miles of the Atlantic coastline—delivering a 14-foot storm surge to New York and crippling the nation's financial capital. The storm showed just how unprepared New York and other coastal cities are to handle flooding from weather disasters.

"As bad as Sandy was, future storms could be even worse," Bloomberg said in a speech on June 11 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, an industrial park severely damaged by nearly five feet of floodwater during Sandy. "In fact, because of rising temperatures and sea levels, even a storm that’s not as large as Sandy could, down the road, be even more destructive."

Roughly 20 percent of cities around the globe have developed adaptation strategies, according to a 2011 estimate by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But no other local government has pledged to spend more—and across so many different issue areas—than New York City, according to interviews with nearly a dozen experts on climate adaptation.

"I think it would be hard to be more comprehensive than New York," said Heather McGray, co-director of the vulnerability and adaptation initiative at the World Resources Institute.

New York's proposals are based on hyper-local climate models specific to the city using the most up-to-date science available. The models, which predict climate trends through the 2050s, were crunched by the New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC), an independent group of scientists and engineers established in 2008 as part of PlaNYC, the city's original sustainability and climate strategy.

"I would say that with this plan, New York City has confirmed its standing as a global leader on climate adaptation," said Radley Horton, a climate scientist at Columbia University's Earth Institute and the climate science lead for the panel.

Even so, Horton highlighted the plan's limits. "It's impossible to make any city fully resilient in the face of this inexorable rise in sea level," he said. Sea level rise in New York City has averaged 1.2 inches per decade since 1900, nearly twice the observed global rate. The NPCC estimates that in less than four decades the city's harbor could be 2.6 feet higher than it is today.

According to climate models, if countries don't quickly and drastically reduce their emissions by the 2050s, the earth's climate system will pass certain tipping points—such as the melting of the Greenland or Antarctic ice sheets—where climate change and its impacts will become unstoppable and irreversible.

Scientists are concerned that even the worst-case projections envisioned in Bloomberg's plan could be too conservative. That's because the model's projections stop in the 2050s, even though they will be used to develop construction guidelines for buildings that could stand in New York's floodplain for centuries.

"Look around," said Klaus Jacob, a geophysicist at Columbia University and a NPCC member. "New York City is filled with buildings and systems that were put in place 100-plus years ago. This means that whatever projects are being proposed will be around for a long time."

Jacob thinks the city's climate adaptation projects should be designed to handle climate conditions far worse than even the NPCC's most severe estimates, particularly on sea level rise. The panel is currently extending its projections through 2100, though it's unclear how the Bloomberg administration will use them since it has already published its recovery plan.

Philip Orton, a physical oceanographer at the Steven Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J. who worked on the NPCC report, also question Mayor Bloomberg's assertion during the plan’s unveiling that "as New Yorkers, we cannot and will not abandon our waterfront ... We must protect it, not retreat from it."

"At some point, I suspect we'll have to abandon at least some areas," said Orton, whose opinion is shared by Jacob. "There'll be no other choice."

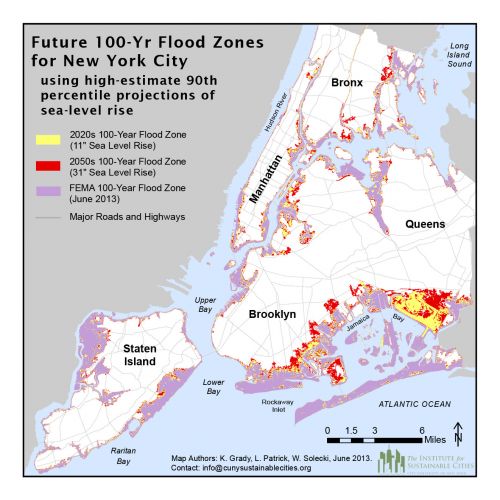

Areas

that are expected to be in a 100-year flood zone in the 2020s

and 2050s as sea levels rise from global warming, according to

new projections by the NYPCC.

Areas

that are expected to be in a 100-year flood zone in the 2020s

and 2050s as sea levels rise from global warming, according to

new projections by the NYPCC.

The Science

According to the NPCC, the next few decades will be substantially worse for the city than was estimated only four years ago, the last time the panel modeled climate change. That's partly because global carbon emissions continue to increase, but mainly because of improved modeling.

Temperatures could rise 3.2 degrees Fahrenheit by the 2020s, compared to the 3-degree Fahrenheit rise the panel predicted in 2009, according to the models. By mid-century, New York City could warm by 6.6 degrees Fahrenheit—an increase of 32 percent over the panel's earlier 5-degree Fahrenheit prediction. Limiting warming to 2 degrees Celsius is seen as crucial to avoid the catastrophic effects of climate change.

The new models show that nearly one-quarter of the city will be in a floodplain by the mid-2050s, with large swaths of Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island prone to frequent widespread flooding. The number of intense hurricanes to hit New York City will increase, as will extreme winds and heavy rain.

Sea levels in New York Harbor will likely rise four to eight inches by the 2020s, with a worst-case scenario of 11 inches. By the 2050s, they could rise 11 to 24 inches—nearly double what the NPCC projected four years ago—with the worst case being 31 inches. Rising seas will make storm surge more severe—meaning that in just a few decades even small storms could cause the type of flooding unleashed by superstorm Sandy.

The new research by the NPCC was done at the request of Mayor Bloomberg in the weeks following superstorm Sandy. The mayor asked the panel to produce updated climate projections that could become the foundation for a recovery plan that would fortify the city against future global warming impacts. The panel published its results on June 10, one day before Mayor Bloomberg announced his $19.5 billion plan.

The scientists improved the methodology they used in 2009 by using a global climate model developed for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's upcoming Fifth Assessment Report, which can project future climate in more detail and on a smaller scale than previous models. This model can also better handle localized features like cloud formation and rainfall. The scientists then honed their results to focus on a 100-mile radius around New York City, a rare level of detail for climate projections.

To create the projections, the team modeled two separate emission scenarios. In one, global greenhouse gas concentrations stabilized after 2100 due to substantial emissions reductions. The other scenario showed no reduction in carbon dioxide emissions.

Cynthia Rosenzweig, the NPCC's co-chair and a climate scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, said hyper-local climate projections like those generated by her and her colleagues could fill a critical gap: The IPCC assessments model regional climate impacts, but for communities to create effective climate action plans, they need more focused results, she said.

"We're working with cities across the globe to start initiatives like this," Rosenzweig said at a briefing for reporters last week.

Read: 6 of the World's Most Extensive Climate Change Adaptation Plans

Who Will Pay for It and What's Next

Lauren Passalacqua, a spokeswoman for the Mayor's Office, said the administration consulted with more than 30 city, state and federal organizations and met with more than 320 community groups to develop the 438-page plan, which took six months to complete.

The Bloomberg administration estimates that the cost of implementing and researching the plan's 250 proposals will total $14 billion over a 10-year period. The plan also factors in the cost of certain post-Sandy recovery efforts, bringing its total price tag to $19.5 billion—only slightly higher than the $19 billion in damage and loss of economic activity wrought by Sandy, making it both an adaptation and a disaster recovery plan.

Eighty percent of the money will go to repairing homes and streets damaged by Sandy, retrofitting hospitals and nursing homes, elevating electrical infrastructure, improving ferry and subway networks and fixing leaky drinking water systems. The rest will go to building or researching floodwalls, restoring swamplands and sand dunes, and other coastal flood protections.

About half of New York's plan will be funded by federal aid and city capital that's already been allocated, and the city government expects to provide an additional $5 billion. That leaves a funding gap of at least $4.5 billion.

Some components of the plan require approval or action from outside City Hall, including an initiative to set new resiliency standards for electric utilities and rebuilding programs that would use federal housing funding. Multiple city agencies will also have to coordinate with one another to determine how the money is divvied up.

Ultimately, how quickly the plan's initiatives are approved and implemented will determine its success in making New York City more resilient, said Juan José Daboub, a former finance minister of El Salvador and the founding CEO of the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index, a metrics tool that ranks countries on their climate change vulnerability and their levels of preparedness.

"If the $20 billion are indeed invested in an efficient and timely manner, this would certainly become one of the greatest and most comprehensive examples in the world,” he said.

© InsideClimate News