It's the best of times and the worst of times for grain sorghum in Nebraska.

On the dark side, last year's harvest of about 60,000 acres was the smallest since Barb Kliment joined the ranks of sorghum promoters in 1981. On a much brighter note, the managers of ethanol plants in Trenton and Ravenna are pushing hard to make a crop also known as milo the main ingredient in their renewable fuels recipes.

"They are certainly letting it be known that they have the capacity and the interest to purchase large volumes of sorghum," Kliment, executive director of the Nebraska Grain Sorghum Board, said Monday.

Drought hardiness should be a big selling point for a crop that tends to outlast corn and soybeans in unirrigated settings.

But its attractiveness in ethanol circles is coming more from its December designation as an advanced biofuel by the Environmental Protection Agency -- and from the financial incentives that go with that.

Ralph Scott of Trenton Agri-Products said his plant is among those that can switch from corn to grain sorghum without retrofitting or threatening its annual capacity of 50 million gallons per year.

"We're trying to encourage it," Scott said. "We're trying to tell producers that, if they will grow it, we will use it."

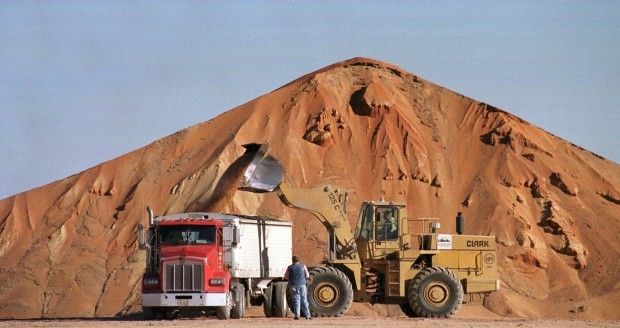

In fact, the southwest Nebraska plant has substituted up to 30 percent reddish-orange sorghum berries for yellow corn kernels in the past.

He would go to 100 percent, if he could, Scott said.

"The issue has been, out here, that there's not a large enough supply, so we're always just supplementing with grain sorghum."

Across the border in Kansas, Gov. Sam Brownback has made it a personal mission to win grain sorghum converts.

One frame of reference is the receding shore line at Cheney Reservoir, water source for the city of Wichita.

"We need people to be thinking differently," Brownback said in a story that appeared in the Wichita Eagle on Friday.

Brownback struck a blow for water conservation despite two major snowstorms that left as much as 46 inches of snow in south-central parts of the state.

Nebraska, the nation's leading irrigating state, enjoys that status because it's much better endowed with groundwater resources than Kansas. On the other hand, its 2013 snowfall has been below normal and a drought of historical proportion shows no sign of easing.

Furthermore, a three-year study in the Lawrence, Neb., area determined that grain sorghum lost two inches less water to evapo-transpiration from 2009 through 2011 than corn in unirrigated fields.

"Sorghum was more economical for our particular study than corn or soybeans were," said Jenny Rees, based at Clay Center as a University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension educator.

Nebraska Agriculture Director Greg Ibach acknowledged that Kansas was making "quite a push with its director of agriculture and everything" toward "more water-sipping crops."

But Ibach rejected suggestions that Nebraska would take a single-minded approach toward corn planting this spring as long as the price per bushel stays above $7.

"I don't necessarily think that's true," he said.

In the Republican River Basin, for example, where irrigation restrictions are getting stiffer, grain sorghum could be in the mix.

Abengoa is looking at grower contracts in the Ravenna area as a way to get around the problem of much diminished supplies of sorghum because of the multiyear surge in prices for corn and soybeans.

Todd Sneller of the Nebraska Ethanol Board can see what's on the minds of management people at Abengoa.

"The only way it works is with a collaboration between an ethanol producer and local farmers."