Chad 'Corntassel' Smith Talks About Embracing One's Legacy

In 1991, I worked for the late Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Wilma Mankiller. I was walking down the hall of one of our buildings, and I overheard one person tell another, “We can’t do that—the Bureau of Indian Affairs won’t let us.” It was a fascinating moment that piqued my curiosity; why did our people believe it, and when did such a fatalistic belief sneak into our national psyche? It was a prevailing thought among employees that the BIA had some strict supervision and veto power over the Cherokee Nation. It was not true. The Cherokee Nation was a sovereign government in the world community of governments before the United States (and the BIA) ever existed, and I believed in our history the Cherokee Nation had always determined its own course. So why did our people believe the Cherokee Nation was something less than the “dependent domestic nation” that the U.S. Supreme Court said it was as early as 1831?

Coupled with the idea that our managers needed to know the past in order to make good decisions in the present, I asked Principal Chief Mankiller if I could develop and teach a Cherokee legal history course. Of course, she encouraged me to do so, and I began to assemble everything I could find as source documents: treaties, maps, articles, movies, slides, excerpts from books, random quotes and more. The course book was organized chronologically and covered Cherokee history from 1700 to the present. In 1991, the 40-hour course was first taught in our historic capitol by me and Pat Ragsdale, who was a director of tribal operations.

After completing the class, one new employee said, “The first day, I got mad; the second day, I wanted to cuss and spit; and the third, I wanted to get a gun and shoot someone. The fourth day, I was just proud to be a Cherokee.”

The class became a life-changing experience for many. Although I had not believed in the concept of historic grief, I did after teaching the class several times, because by the third day of class, I could sense this cloud of grief rise from the class and dissipate. Those most reluctant about attending a 40-hour history course—because “It’s been 30 years since I was in school” or “I have work to do” or “I never liked history anyway” or “I work in maintenance and don’t need history”—were the most enthused after completing the class. Some would come to the class with a chip on their shoulder against the white man and the U.S. government because of their understanding of our history. The treatment of the Cherokee Nation by the United States, as laid out with primary documents in the class, was much more brutal than they ever imagined.

However, instead of leaving the class more embittered, the opposite occurred. People left the class understanding that if our ancestors survived horrific episodes—eradication of our people by disease in the 1730s, genocidal warfare by Americans in the 1770s, forced removal in the 1830s, abandonment in the American Civil War, coerced assimilation and liquidation of the Cherokee Nation’s resources in 1906, the Grapes of Wrath exodus from Oklahoma during the Depression, relocation and termination in the 1950s and bureaucratic imperialism today—then each of them had a legacy that inspired them with determination to carry on and do better. The result of the class on individual perception and behavior was quite moving.

When I took office, we hired Julia Coates, an outstanding Cherokee college professor, to teach the class full-time. Post-class surveys revealed 90 percent of the students reported it changed their lives. Coates received hundreds of personal testimonies from students whose lives the course changed. People took the class over and over. It was the only class I have ever heard for which the daily attendance increased rather than declined. Later, employees were required to attend. To date, more than 10,000 people have completed the course including employees, Cherokee citizens in urban communities and the general public. It received a best practices award from Harvard University. It also helped describe Point A for the Cherokee Nation, but even more important, it gave a glimpse of what Point B, the future, could be.

We Won’t Even Be Here Then!

A good place to learn about the future is to study the past.

I knew from our research and history class where the

Cherokee Nation was economically, socially, politically and

culturally 100 years ago. So the obvious question was,

“Where could we be 100 years from now?”

Shortly after my first election as principal chief, we began discussing a long-term plan for the Cherokee Nation. (It is common to have a five-year plan in business.) I suggested regaining what U.S. Senator Dawes observed about us over 100 years ago: Every Cherokee owned his home, there was not a pauper in the Nation, and the tribe owed not a dollar. In 1888, the Cherokee Nation was economically self-sufficient; we had a strong sense of identity and culture; and we had cohesive communities that helped individuals in tough times and enjoyed the good times. Today, poverty and social well-being statistics are dismal and epidemics of methamphetamine use, diabetes, domestic abuse, and other physical and social maladies are staggering. So why not come up with a plan that in a hundred years, we could be where we were one hundred years ago?

During the course of a community talk, I mentioned having a 100-year plan. A community member asked, “Why have a 100-year plan when we won’t even be here then?” I answered, “Yes, that is true, we won’t be, but who will?” It seemed like a light went on. Everyone in the room then understood that the very reason for having a 100-year plan was the fact that we would not be here. Our children, grandchildren, and generations yet unborn would be. We had a duty, an obligation, a responsibility and an honor to pass on to our descendants a legacy that we inherited from our ancestors who died before we knew them. We received a gift from those relatives we never knew because they came generations before us and knew we must pass it on to those we will never know because they will come generations after us.

It was hard for people to think in 100-year terms, and who could blame them? So in 2003, Mike Miller, our communications officer, produced a videotape shot in a local television news station. It had two six o’clock newscasts portraying events 25 years in the future; it was called 2028. The first scenario was based on the Cherokee Nation following the norms of non-Indian governments where political expediency, self-interest, and shortsightedness were the norms. The news anchors reported high rates of diabetes, crime, methamphetamine use, joblessness and the death of the last Cherokee speaker. The sports guy reported on Indian stereotype mascot teams playing professional baseball and football.

The second television newscast addressed the same issues but in a scenario where the Cherokee Nation adhered to its 100-year plan and made decisions based on cultural principles, what was good for generations to come and visionary aspirations. The newscast reported Cherokees had a life expectancy five years longer than the majority population, the Nation reacquired 1 million acres of land, the Cherokee Nation’s Delegate to Congress was instrumental in bringing lasting peace to the Mideast, there had been no reported case of methamphetamine use in five years and a 100-member Cherokee youth choir sang to the president of the United States in Cherokee when he visited the Cherokee Nation.

The sports guy reported on the national stickball championship with sellout crowds watching two Cherokee community teams play.

The message of the video was that we had a legacy as a people who faced adversity, survived, adapted, prospered and excelled. The 2028 video asked questions about what path we would choose. Could we transcend mainstream gang politics and have the discipline to live up to our legacy? Could we, over the course of several generations, come to face emerging adversities with calm, call upon our historical stamina to survive, use our intelligence to adapt, work for prosperity and demand excellence of ourselves? Did we as a government and people want to have something to show for a day’s work and a lifetime’s effort? Could we continue our legacy with a 100-year plan?

You Will Be What You Want to Be

I gave the 2009 graduation speech at Sequoyah High School.

Ninety of the school’s 400 students were graduating. At that

time, I thought that my speech was good, would challenge the

students to want to be something and would encourage them to

achieve whatever it was that they wanted to be. Here is how

it started: A standard graduation speech tells you that you

can be anything you want to be. That is true. I suggest you

will be what you want to be. If you really want something,

you will make decisions, consciously and subconsciously, to

get it. You will eat, sleep and work to be what you want to

be.

When I wrote this speech, I was wrong. Sort of. It might sound odd, but the vast majority of those students, their parents, and their grandparents did not imagine, much less understand, all of the job opportunities, occupations and professions they could possibly strive for and achieve. They had not seen those achievable occupations because they were often isolated in their communities; they did not know anyone who held those occupations; their aspirations were often limited to the minimum wage jobs that were familiar to them.

How could I challenge them to want to be something when they did not know the range of possible careers? How do you pursue a dream you have never seen? How do you learn what you do not know?

As principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, I held educational summits and discussed potential solutions to breaking the cycle of poverty with school administrators throughout northeastern Oklahoma. I learned that as many of 60 percent of Cherokee children were raised by their grandparents in core Cherokee areas, because of single parent families or both parents working to make ends meet. Most of these students, their parents, and especially their grandparents were not aware of the career opportunities they could achieve. They felt intimidated and powerless due to the changing economic and technological landscape. They had little hope because they could not envision successful futures for themselves and set goals to achieve success.

So what should the Cherokee Nation want? Should they want to regain what they had 100 years ago? Did enough of our people know our history and culture to agree on a vision for rebuilding the nation? Did we, as a group, care about

nation-building? Was there something better out there for us and our families?

As a public defender in Tulsa County, Oklahoma, in the late 1990s, I represented indigent people in criminal cases. I remember one young man I interviewed in jail when he was waiting to be sentenced by the judge for drug crimes. He had just turned 18 and had lived through a terrible childhood. As a child, he was passed from foster home to foster home, over one third of his body was burned in an accident, and he had gotten into a lot of trouble stealing and doing drugs.

He was the kind of kid that every policeman knew his birthday and was waiting for him to turn 18. He thought he could sway the judge by getting a job. He told me about getting a job at McDonald’s. His face lit up as he spoke about being around people, helping others and not looking over his shoulder wondering if a drug dealer was going to approach him for money he owed them. He said with a sense of triumph, “My girlfriend and me don’t fight as much.”

But when he talked about his days dealing drugs and hanging out with gangs, his face turned dark. It dawned on me that this young man had never seen anything in his life but crime, abandonment and fear. His job at McDonald’s gave him a glimpse of a life he never knew was possible: openness, the ability to earn and security. After listening to him, I understood that many of us just don’t know what good things are outside our immediate environment. So how do we find out about them?

Point B Is Reachable

One of the great blessings I had as principal chief was that

I saw visions attained and dreams come true. I would not

have believed 10 years ago what our staff would accomplish

in that time.

In 1999, when I was running for principal chief, I attended a community meeting where my opponent quickly put together a handful of young Cherokee students to sing in Cherokee. Their appearance was shabby, they were disorganized, and the performance was poor. I felt bad for the students pushed into such a situation. Could we do better than that? Could we have a Cherokee youth choir to be the counterpart to the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, even though it may not be as large? After all, gospel music sung is nice, and when sung by children it is beautiful, and when gospel music is sung in Cherokee by children, it is angelic. As one elderly Cherokee woman remarked, “I was surprised God spoke English; I thought he spoke only the most dignified Cherokee.” Although there were no Cherokee speakers under 50 years old, could we not teach young people to sing in Cherokee?

We knew our Cherokee language was dying, and language is the vessel of cultural intelligence. How could we revitalize our language? We hired a choir director and Cherokee speaker to recruit children for a youth choir, teach them to sing Cherokee and to perform at community events. We challenged the director and her assistant to develop the “Cherokee Mormon Tabernacle Choir.” As with all things in development, the first several years were slow, and the choir faced

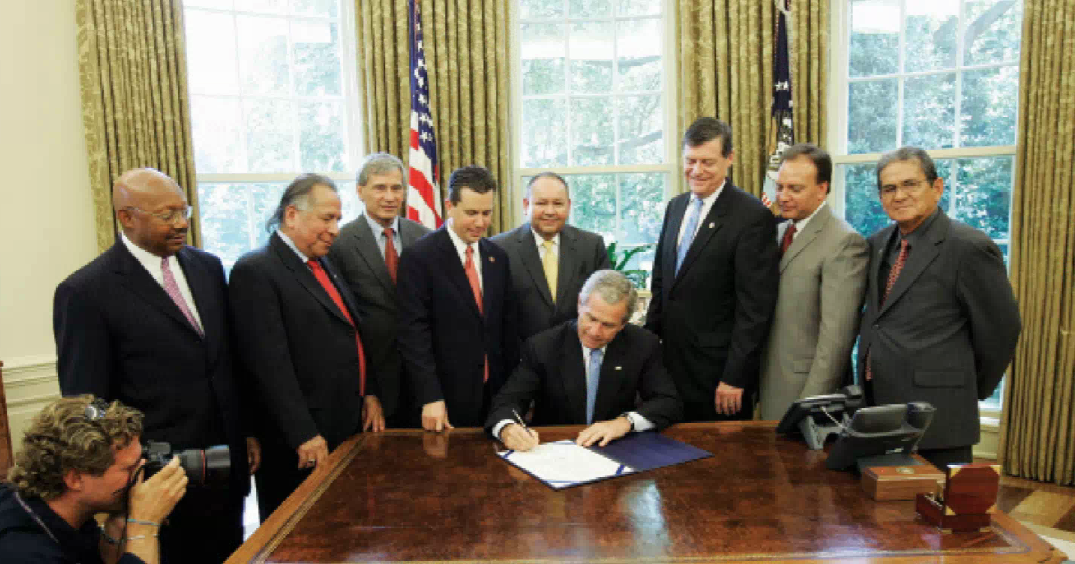

challenges. But soon they grew from 10 members to 40, the quality of the singing improved, they appeared more places, and more requests came in. Individual choir members grew in confidence and leadership. We produced and published 10 CDs of Cherokee gospel and patriotic music; we finished a CD of Motown in Cherokee language just for the fun of it. The Cherokee National Youth Choir has won numerous Native American Music Awards, was inducted into the Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame and has performed at the White House. They have performed with Dolly Parton, Vince Gill, the Oakridge Boys, the Tulsa Pops Symphony and others. Their CDs are played in Cherokee households and at daycares and funerals.

A positive unintended consequence that should have been obvious when I started the choir was that the choir was not only a means to revitalize our Cherokee language and advance cultural attributes, but it also developed leaders.

Every trip the choir took, the bus drivers, hosts, attendees, and casual observers remarked on how polite, positive and pleasant the members were. There are 120 students who have been in the youth choir, and they offer story after story of how singing Cherokee before audiences, visiting new places, representing the Cherokee Nation and taking responsibility for their musical part and as ambassadors has changed and improved their lives.

When students join the choir, they receive a medal recognizing them as ambassadors of the Cherokee Nation, and each member has performed that role well. So an off-the-cuff idea grew into a project that changed the lives of scores of Cherokee youth, touched the hearts of hundreds of Cherokees who listened to the music of the choir and promoted the learning of our language. People often ask, “Who would have thought 10 years ago that the choir would be what it is today?”

I am also proud of what we did with Sequoyah Schools (grades 9–12), a Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Its history goes back to the American Civil War, when the Cherokee Nation established an orphanage due to the loss of life by Cherokees fighting on both sides, which displaced many Cherokee children from their families. In 1906, the federal government took over operations and established it as an orphan training school and then later as a boarding school.

My dad graduated from Sequoyah in 1940 and was pleased to have three meals a day, a warm place to sleep and an opportunity to learn a machine shop trade. It was a home for hundreds of children who, because of the Depression or dysfunctional families, would have otherwise had no hope for a safe and comfortable life.

By the time I took office as principal chief, the school had been contracted by the Cherokee Nation for operation but had gained a reputation as a school of last resort. People remarked that you went to Sequoyah if you got kicked out of other schools. Capacity was 350 students, but it had an enrollment of only 205. I wanted to build a leadership academy out of respect for my dad. We recruited staff and coaches, imposed admission guidelines and invested in facilities and curriculum.

Since that time, Sequoyah has become a School of Choice (the school’s motto), and enrollment is over capacity with 150 students on a waiting list. By 2011, the school’s sports teams had excelled with state championships, 44 students had received Gates Millennium Scholarships, and students enjoyed current interests such as robotics, music, art and drama. Today every student works on an Apple computer, and there is no armed security or fences.

Sequoyah enjoys a sense of family and leadership. Thousands of family and community members attend football and basketball games in support of the students striving for excellence. Alumni and community people say, “Who would have thought 10 years ago that Sequoyah would be what it is today?”

This excerpt is from Leadership Lessons From the Cherokee Nation, by Chief Chad Smith ©2013, McGraw-Hill Professional; reprinted with permission of the publisher.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/05/22/chad-corntassel-smith-talks-about-embracing-ones-legacy-149431