Consumer Reports investigation: Talking turkey

Our new tests show reasons for concern

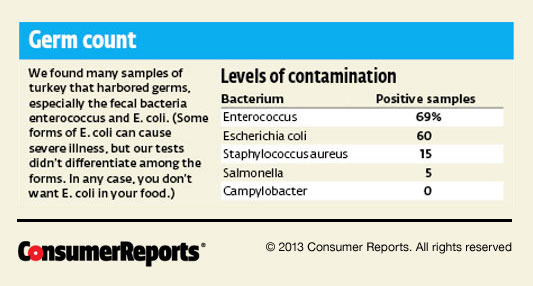

In our first-ever lab analysis of ground turkey bought at retail stores nationwide, more than half of the packages of raw ground meat and patties tested positive for fecal bacteria. Some samples harbored other germs, including salmonella and staphylococcus aureus, two of the leading causes of foodborne illness in the U.S. Overall, 90 percent of the samples had one or more of the five bacteria for which we tested.

Adding to the concern, almost all of the disease-causing organisms in our 257 samples proved resistant to one or more of the antibiotics commonly used to fight them. Turkeys (and other food animals, including chickens and pigs) are given antibiotics to treat acute illness; but healthy animals may also get drugs daily in their food and water to boost their rate of weight gain and to prevent disease. Many of the drugs are similar to antibiotics important in human medicine.

That practice, especially prevalent at large

feedlots and mass-production facilities, is speeding

the growth of drug-resistant superbugs, a serious

health concern. People sickened by those bacteria

might need to try several antibiotics before one

succeeds. (Related: Read "Has

Your Steak Been Mechanically Tenderized?" That

report details a process that can drive bacteria

like the deadly pathogen E. coli O157:H7 from the

surface deep into the center of the meat.)

Among our findings:

- Sixty-nine percent of ground-turkey samples harbored enterococcus, and 60 percent harbored Escherichia coli. Those bugs are associated with fecal contamination. About 80 percent of the enterococcus bacteria were resistant to three or more groups of closely related antibiotics (or classes), as were more than half of the E. coli.

- Three samples were contaminated with methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which can cause fatal infections.

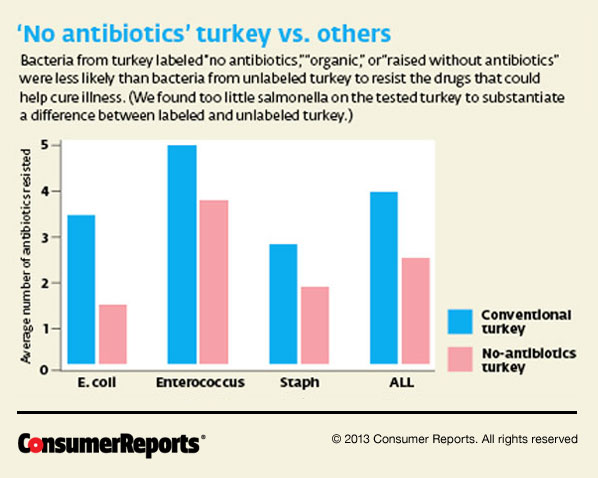

- Ground turkey labeled “no antibiotics,”

“organic,” or “raised without antibiotics” was

as likely to harbor bacteria as products without

those claims. (After all, even meat from organic

birds can pick up bacteria during slaughter or

processing.) The good news is that bacteria on

those products were much less likely to be

antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

Get more details on our data.

From barn to burger

Conventionally raised turkeys are fed mostly corn and soybean meal plus a vitamin and mineral supplement. They usually get FDA-approved antibiotics that may be given in low doses without a prescription. Before the birds are killed, antibiotics must be withdrawn to ensure that residues clear from the birds’ systems.

But harm may already have been done. Although the antibiotics eventually kill off vulnerable barnyard bugs, bacteria that are immune to their effects can flourish and spread. They can exchange genetic material with other bugs, further accelerating antibiotic resistance. And bacteria on turkeys can develop resistance to similar drugs that aren’t even given to turkeys.

Some bacteria that end up on ground turkey, including E. coli and staph aureus, can cause not only food poisoning but also urinary, bloodstream, and other infections.

Antibiotics aren’t allowed in turkeys labeled “organic,” “no antibiotics,” or “raised without antibiotics.” (Sick birds may be treated, but they’re then sold to nonorganic markets.) Organic birds must eat only certified organic feed and pasture, which means no genetically modified organisms; and production of those birds must not contribute to contamination of soil or water. Producers of organic and free-range turkeys must demonstrate to the Department of Agriculture that they’ve allowed birds “access to the outside,” though that phrase is not specifically defined and some birds may not venture outdoors.

Such steps are among the requirements for raising a food animal sustainably—without drugs and in a way that’s more healthful for animals and people.

Indeed, when we focused on antibiotic use, our analysis showed that bacteria on turkey labeled “no antibiotics” or “organic” were resistant to significantly fewer antibiotics than bacteria on conventional turkey. We also found much more resistance to classes of antibiotics approved for use in turkey production than to those not approved for such use. Consumers Union, the advocacy arm of Consumer Reports, believes that the FDA should ban all antibiotics in animal production except to treat illness.

A need for stricter limits

When any food animal is slaughtered, the bacteria that normally live in its gut without causing harm can wind up on its carcass. To limit contamination, federal law requires processors to create a Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point plan. For turkey processors, HACCP includes steps for washing and chilling carcasses throughout processing to reduce the growth of harmful bacteria and contamination of the finished product.

But HACCP doesn’t require eradication of harmful bacteria. In fact, salmonella is permitted in up to half of the ground-turkey samples that the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) tests at processors’ plants. And bugs that remain can keep growing until the turkey is cooked.

In 2011 Cargill Value Added Meats Retail announced two voluntary recalls of a total of 36 million pounds of conventionally raised ground turkey—among the largest recalls of poultry meat in U.S. history—due to possible contamination with a resistant strain of salmonella Heidelberg. The superbug was traced to a Cargill establishment in Springdale, Ark. In all, 136 people fell ill during that outbreak, according to the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and one of those victims died.

“As we’ve publicly stated over the past year and a half, no stone was left unturned in our efforts to determine the originating source of salmonella Heidelberg associated with the ground-turkey recalls, yet to this day we do not know the origin of the bacteria linked to outbreak of illnesses,” said Mike Robach, vice president of corporate food safety and regulatory affairs for Cargill in Minneapolis. He provided a long list of steps that Cargill has taken since the outbreak to make its ground turkey safer.

In the wake of the recalls, the FSIS required all ground-poultry processors to review and update their safety procedures, paying special attention to the sanitation of equipment. The agency told us that it also plans to conduct a risk assessment of salmonella and campylobacter (another food-poisoning bacterium) in ground-turkey products. The goal: a new standard for salmonella and, possibly, campylobacter.

Eight ground-turkey samples in our tests, conducted a year after the recalls, harbored salmonella that resisted three or more antibiotic classes. One of those samples came from a package of turkey processed at Cargill’s Springdale plant. It harbored a strain of salmonella Heidelberg that was not the outbreak strain but resisted the same antibiotics. Even a finding of the outbreak strain, the FSIS said, “likely would not trigger a specific follow-up action by FSIS if steps were previously taken for the affected establishment to regain control of its operations.”

Consumers Union says the current salmonella standard isn’t strict enough, and is urging the USDA to allow no more than 12 percent contamination in ground-turkey samples, a standard most of the industry already meets.

Any improvement will come too late for consumers such as Diana Goodpasture, 66, of Akron, Ohio. She was sickened with salmonella Heidelberg from ground turkey in June 2011 and was hospitalized for five days. “I’ve had complications ever since then,” she says. “I’m still seeing a gastroenterologist. I don’t know that I’ll ever be well.”

How resistant to antibiotics?

We determined whether samples of four bacteria isolated from our tested ground turkey could survive exposure to as many as 16 antibiotics at levels usually effective against those bugs. The antibiotics we tried differed with each bug and included ampicillin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, and others often used to treat the illnesses those bacteria cause. Classes are groups of similar antibiotics. Three of the 39 samples of staph aureus harbored MRSA, a potentially deadly bacterium.

|

Bugs immune to drugs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterium | Samples tested |

Resisted one or more antibiotic

classes |

Resisted three or more antibiotic classes |

| Enterococcus | 178 |

177 |

144 |

| Escherichia coli | 155 |

135 |

82 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 39 |

34 |

8 |

| Salmonella | 12 |

11 |

8 |

What you can do

Common slip-ups while handling or cooking ground turkey can put you at risk of illness. Although the bacteria we found are killed by thorough cooking, they can produce toxins that may not be destroyed by heat. Take the following precautions:

- Buy turkey labeled “organic” or “no antibiotics,” especially if it also has a “USDA Process Verified” label, which means that the USDA has confirmed that the producer is doing what it says. Organic and no-antibiotics brands in our tests were: Coastal Range Organics, Eberly, Giant Eagle Nature’s Basket, Harvestland, Kosher Valley, Nature’s Place, Nature’s Promise, Nature’s Rancher, Plainville Farms, Wegmans, Whole Foods, and Wild Harvest.

- Consider other labels, such as “animal welfare approved” and “certified humane,” which mean that antibiotics were restricted to sick animals.

- Be aware that “natural” meat is simply minimally processed, with no artificial ingredients or added color. It can come from an animal that ate antibiotics daily.

- Know that no type of meat—whether turkey, chicken, beef, or pork—is risk free.

- Buy meat just before checking out, and place it in a plastic bag to prevent leaks.

- If you will cook meat within a couple of days, store it at 40° F or below. Otherwise, freeze it. (Note that freezing may not kill bacteria.)

- Cook ground turkey to at least 165° F. Check with a meat thermometer.

- Wash hands and all surfaces after handling ground turkey.

- Don’t return cooked meat to the plate that held it raw.

Sickened by a turkey burger?

Hours after she grilled a turkey burger for dinner in June 2011, Diana Goodpasture, 66, of Akron, Ohio, says she felt awful. “In the middle of the night, I woke up and I was sick,” she says. “I started to get an upset stomach and diarrhea, and then it just got progressively worse from there.”

Goodpasture, a van driver, says she thought she’d caught a stomach flu, so she stayed home for a few days. But the gastrointestinal symptoms and crampy abdominal pain worsened. “It got so bad that my kids said, ‘You have to go to the hospital,’ ” she recalls. Goodpasture was hospitalized at Akron General Medical Center for five days.

Tests showed that she’d fallen ill from salmonella Heidelberg. The leftover ground turkey she’d frozen after dinner also tested positive when analyzed by the Summit County Public Health Department.

Almost two years later, Goodpasture says she’s still not completely well. “It has really messed up my intestinal system. And from what I can tell, that’s just a lifetime thing I’m going to have to deal with,” she says. “It changed my whole life.”

Copyright © 2006-2013 Consumer Reports.

http://www.consumerreports.org/turkey0613