For biofuels, the future won't look much like the past. We're heading, some believe, for a post-ethanol age.

Today, nearly all plant-based liquid fuels are either used to make ethanol, which is blended with gasoline, or biodiesel. But efforts to increase the amount of ethanol in gas are opposed by auto makers and others who say the environment and economy are better served by more efficient engines and the shift to hybrid, electric and natural-gas vehicles. There are critics, too, who say making biofuel from edible plants—most ethanol is based on corn or sugar cane—is a poor use of land and crops needed to feed growing populations.

From the Archives

Click on the image for the complete article.

Now energy experts see a growing role for new biofuels that use nonedible plant material and are hydrocarbons, like petroleum fuels, and so don't require a separate infrastructure.

"Biofuels have a much broader future than ethanol," says Thomas Foust, director of biofuels development at the National Bioenergy Center, part of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. He adds that new methods of making fuels directly from biomass—without need of enzymes, bacteria or other microorganisms—"look promising from an economic perspective."

That promise isn't likely to become a reality anytime soon. More investment is needed to fine-tune and scale the technology. But here is the outlook for current and advanced biofuels:

Ethanol

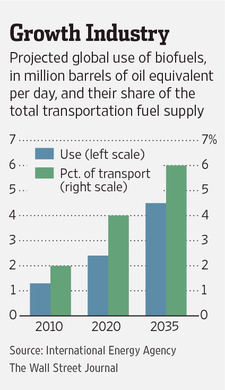

Ethanol will be with us for a long time to come. The International Energy Agency says world consumption of biofuel—largely ethanol and biodiesel—could rise to the equivalent of 4.5 million barrels of oil a day by 2035, up from 1.3 million, or 2% of total transportation fuels, in 2010.

Ethanol produced in Brazil from sugar cane will account for much of the projected growth. Cane has higher energy content than corn-based ethanol, and the crop doesn't need irrigation or harshly deplete the soil. Also, the majority of cars in Brazil can run on gasoline or 100% ethanol.

Willows being grown for fuel. David Parsons/NREL

Amid growing pressure to make less ethanol from edible crops, some have pinned their hopes on nonfood plant materials. Such fuels are expected to make up only 18% of total biofuel production in 2035—and that's if more countries adopt taxes on carbon emissions and governments boost ethanol blend rates.

Ethanol made from nonfood sources initially attracted a host of investments. But funding has fallen off largely because of concerns about uncertain future policies, high production costs and difficulties achieving scale.

Both food-based and cellulosic ethanol use microorganisms such as bacteria and enzymes in a costly process that breaks down the raw material into sugars that are fermented.

"Enzymes are code for money," says Michael Webber, deputy director of the Energy Institute at the University of Texas, Austin. "Cellulosic materials were designed by nature to not break down, and to reverse nature is expensive."

A few companies are still trying. Ineos Bio, in Florida, has begun producing nonfood ethanol from crop and wood waste using biofermentation. Last month, Beta Renewables SpA cut the ribbon on a 20-million-gallon-a-year plant in Italy, whose feedstocks include straw from wheat and rice.

But many early investors in cellulosic ethanol have become convinced that the technology may never be cost-competitive.

"Given that cellulosic ethanol from biofermentation is far more expensive and inferior to hydrocarbon fuels—and made from the same feedstock—it makes no economic sense," says Vinod Khosla, head of Khosla Ventures. Mr. Khosla says he hasn't invested in cellulosic ethanol projects in at least four years.

Advanced Cellulosics

The answer, some believe, lies in finding less-costly ways of producing cellulosic fuels.

One method several companies are trying is a thermochemical process that directly converts plant materials into a synthetic gas or bio-oil.

KiOR Inc., KIOR +6.28% backed by Khosla Ventures, is shipping from a commercial facility in Mississippi small amounts of renewable fuels from pine wood biomass. The company, based in Pasadena, Texas, uses a process based on fluid catalytic cracking, widely used by oil refineries, which produces gasoline and diesel that can be used as blendstocks in existing infrastructure.

KiOR recently secured financing to build a second plant on the same Mississippi site. Chief Executive Fred Cannon says production at the combined facilities will produce cellulosic gas and diesel at an unsubsidized cost of about $2.70 a gallon, at the current yield of 72 gallons per ton of feedstock.

Some experts think cellulosic biomass also may have a future as a source of jet fuel. Virent Inc., also backed by venture capital, has produced jet and other biofuels and chemicals from corn-crop residue and wood waste at a plant in Madison, Wis. Earlier this year it delivered 100 gallons to the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory for testing.

"I think jet fuel is the biofuel that has the best prospect," says Wally Tyner, an energy economist at Purdue University. "On the ground you have alternative fuels, natural gas, electric vehicles," Mr. Tyner says. But in the air the choices are more limited. For aviation to cut emissions, he says, the choice is between more engine efficiency or biofuels.

Algae

Microalgae have great appeal as a source of renewable fuels because, unlike crops, they can be harvested on otherwise unusable land, such as desert, and produce high yields. But despite heavy spending by governments, investors and big oil, experts say algae's potential may not be achieved before midcentury.

Companies such as Solazyme Inc. SZYM +1.29% and Sapphire Energy Inc. have achieved production of crude oil from microalgae but have yet to bring down costs or manage to scale production to compete with petroleum-based fuels. Synthetic Genomics Inc., which in 2009 had announced a $600 million commitment from Exxon Mobil XOM +2.20% to commercialize algae-based fuels, said in May that the project had been renewed as a "basic science research program."

Ms. Lemos Stein is a writer in New York. She can be reached at reports@wsj.com.

Copyright ©2013 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304527504579168140813739808