After Contact, Isolated Groups Recover—But at High Cost

For half a millennium, contact with outsiders has meant death for indigenous groups living in isolation in the Amazon forest, but a new study from Brazil shows that some of those groups managed to recover within a decade after contact.

The findings offer a glimmer of hope to peoples decimated in recent decades by violent confrontation or diseases as ordinary as the flu, to which they had no resistance and which they caught from adventurers, settlers, loggers, gold miners, oil field workers or other outsiders.

They also point to steps governments could take to help ensure the survival of groups that choose to live in isolation, according to anthropologist Marcus Hamilton, a post-doctoral fellow at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico and the biology department of the University of New Mexico and an adjunct assistant professor of anthropology at that university.

Brazil is one of the few countries with enough census data to piece together a picture of the impact of indigenous societies’ contact with outsiders. To understand the impact of contact on those groups and their chances of survival, Hamilton and his colleagues sifted through census data from the past 50 years and population estimates going as far back as a century.

After contact, “you always see crash events in these populations,” said Hamilton, lead author of a paper about the study that was published April 1 in the journal Scientific Reports.

“Either you see the crash events in census data, or you see that they are recovering from very small populations.”

But that raised a question, he said: “After they go through these crash events, are they doomed to extinction, are they struggling along at very low numbers, or do you see population growth?”

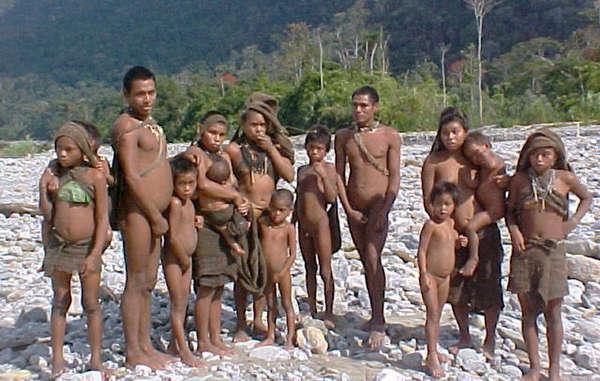

Brazil has 238 contacted Indigenous Peoples, but dozens of isolated groups still live in the Amazon basin, shunning contact with outsiders. The largest concentration is along the border between Brazil and Peru.

The census data showed that the result of contact was “catastrophic” loss, with populations plummeting by more than 80 percent in some cases, reaching the lowest point an average of eight and a half years after contact.

Often, however, that was followed by a turnaround.

“We were very surprised to see that after 10 years or so after contact, they seem to be growing relatively rapidly, in terms of human population growth rates,” Hamilton said.

That does not change the harsh reality of European contact with Amazonian peoples. About three-fourths of those societies vanished altogether, and the others suffered what the researchers call “catastrophic” losses.

Once populations began to recover, however, they grew quickly, Hamilton said. Many have increased by more than 4 percent per year, well above Brazil’s average population growth rate. Although the researchers cannot be sure whether that is entirely from births or whether decimated groups join others, if they live in a territory large enough to provide for their needs and those of future generations, they could survive the catastrophic collapse, Hamilton said.

Survival is not guaranteed, however, especially if the group was small to begin with.

“Contact can very easily wipe out a small group,” he said. “In the history of the contact process, that happens very predictably. If the population is reduced to below about 100 individuals, it seems to be very unlikely that the population will survive.”

That raises a serious question for governments of Amazonian countries where semi-nomadic groups are known to shun contact with the outside world.

RELATED: Uncontacted Tribes Facing Annihilation Without Protection

Brazil’s government has an office charged with protecting those groups, but other countries have fewer safeguards.

Oil drilling is under way in northern Peru, in an area where indications of the existence of a semi-nomadic group have been found. The government has also approved expansion of the Camisea gas field, in southern Peru, farther into a reserve for isolated groups.

RELATED: Indigenous Rights Still Being Trumped By Mining Money in Peru

A controversial plan to expand oil drilling in Ecuador’s iconic Yasuní National Park would also affect several semi-nomadic groups.

RELATED: Cruel Bait and Switch: Correa to Allow Oil Drilling in Amazonian Park

But with little information about the size and movements of isolated groups, it is difficult to gauge how seriously those activities could affect them if contact occurs, even accidentally, Hamilton said.

He and his colleagues hope to test whether data from aerial photos and satellite images could be combined to help policy makers judge a group’s demographic health and help ensure its survival by protecting its territory or taking other steps.

“Ultimately, we’re interested in trying to understand the (outlook) for uncontacted populations and how you might go about collecting scientific data to understand what their future prospects for survival might be without having to go through a catastrophic process” of contact, he said.

© 1998 - 2014 Indian Country Today. All Rights Reserved To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.indiancountry.com