Picture

of a home in the Eagle Ford Shale of South Texas,

one of America’s most active drilling areas. New

workshops there aim to empower citizens who believe

they're beind sickened by air emissions or water

contamination. Credit: Earthworks

Picture

of a home in the Eagle Ford Shale of South Texas,

one of America’s most active drilling areas. New

workshops there aim to empower citizens who believe

they're beind sickened by air emissions or water

contamination. Credit: Earthworks

Virginia Palacios wants to empower the people of south Texas. She and her organization, the Austin office of the Environmental Defense Fund, want them to know they can make a difference in the face of the oil and gas boom that’s sweeping the Eagle Ford region.

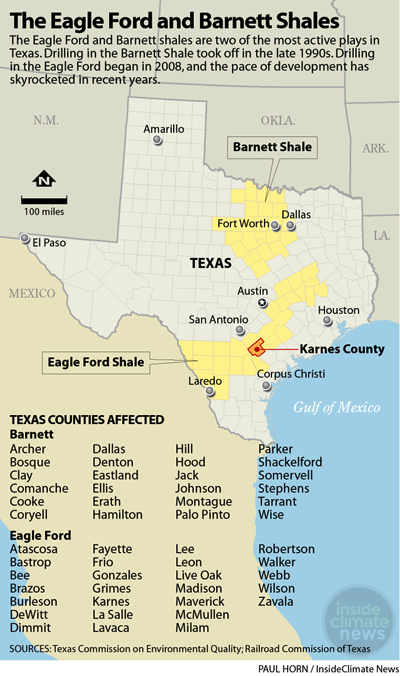

In partnership with the Rio Grande International Study Center, Palacios has helped develop a series of workshops in five heavily impacted counties in the Eagle Ford, a 400-mile-long swath of oil and gas development that reaches from northeast Texas to the U.S.-Mexico border. The goal is to let residents know what resources are available if they believe they are being sickened by toxic emissions, or their water is becoming tainted or their wells are being drained.

People accustomed to a quiet rural lifestyle have found themselves in the middle of a bewildering hubbub of 18-wheel oil trucks, heavy equipment, day and night drilling, smoky flares and leaking emissions. Since 2008, more than 7,000 wells have been sunk and another 5,500 have been approved, making the Eagle Ford one of America’s most active drilling areas.

Palacios and Tricia Cortez, executive director of the Laredo-based Rio Grande center, say they want to head off the kinds of problems that have overwhelmed residents of the Barnett Shale, a 5,000 square mile oil and gas region that stretches south and west from the Dallas–Fort Worth area, where shale drilling began a decade ago.

The lessons learned there provide a blueprint for what's ahead for the Eagle Ford, they said.

"There are consequences that come along with this rapid development," Palacios said. "People are experiencing these impacts and need to know how to respond, need to know what agencies to turn to."

The seminars, which will be conducted in English and Spanish, begin July 17 in La Salle County and end Aug. 9 in Webb County. The roles and responsibilities of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) and the Railroad Commission, the two agencies responsible for regulating the oil and gas industry, will be explained. The part played by groundwater conservation districts also will be outlined.

The idea, Palacios said, is to teach people how to report emissions and suspected water contamination and help them understand the importance of developing baseline water quality assessments and monitoring.

For example, one of the emerging problems near Laredo in Webb County is the growing number of unregulated and illegal oil and gas waste pits that are springing up, Cortez said.

"When people see these, they don't know if what they are seeing is proper or not," Cortez said.

By understanding which agency has responsibility—in this case the Railroad Commission—Cortez said people can be the eyes and ears of the agency to help diminish the improper conduct that many times goes unnoticed.

That’s especially true for the Railroad Commission, which Cortez says is stretched seriously thin. Statewide, the commission has 159 inspectors to oversee 420,181 oil and gas wells—or about one inspector for every 2,600 wells, according to a review of commission by the Rio Grande Center and EDF.

Since drilling in the Eagle Ford began picking up momentum in 2010, residents have filed more 300 complaints with the TCEQ, each offering a glimpse into the problems being faced daily throughout the region. A Frio County woman complained that she "wakes up with an upset stomach and horrible headaches" because of the powerful emissions. An Atascosa County family complained that, "The odor is so bad that their lungs feel as if they will burst."

For every person who has filed a complaint, Palacios worries there are countless others who are suffering and simply don't have a clue where to turn.

"We are concerned that people don't know where to go for help," she said. "And then when they call it's such a complex network they have to navigate that they get overwhelmed."

The TCEQ and Railroad Commission have often been faulted for inaction and having a cozy relationship with the industry.

Even when complaints to TCEQ are sustained, oil and gas companies that break the law are rarely fined. Of 284 complaints filed from 2010 through 2013 in the 24 Eagle Ford counties, only three resulted in fines despite 164 documented violations.

Palacios believes that if more people complain, the agencies and the industry will be more likely to work together to solve the problems.

"The first step is empowering the people," she said. “With that empowerment comes change and a better way of life."

© InsideClimate News