Can you name the single largest user of water in the United States?

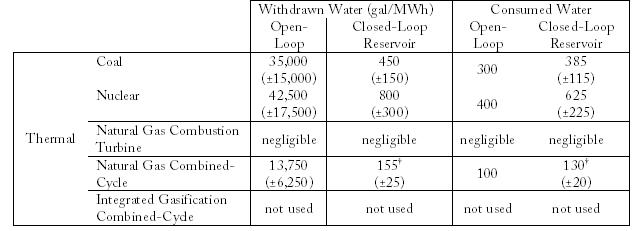

If you said power plants, you were right (see chart below)! More water is required to run power plants than any other industry. In Texas, approximately 157,000 million gallons (482,100 acre-feet) of water annually – enough water for over 3 million people for a year, each using 140 gallons per person per day – are consumed for cooling the state’s thermoelectric power plants while generating approximately 400 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity. Because of this, water is an important consideration in power plant planning.

In New York state, power plant water use is causing some big problems. Daily withdrawals of more than 20 million gallons have annually killed 17 billion fish in various stages of life. Regulators are trying to address the problem by requiring the installation of closed-loop cooling, which would reduce water requirements by 93-98%. Is that a good idea? It depends. Simply requiring one type of cooling system may not consider all the factors which is important because retrofitting all existing plants can be very expensive and can lead to unintended consequences.

Three ways to cool and why does it matter?

The typical power plant uses a fuel (coal, gas or nuclear) to heat water into steam, which then turns a turbine connected to a generator, which produces electricity. The steam is then condensed back into water to continue the process again. This condensation requires cooling either by water, air, or both.

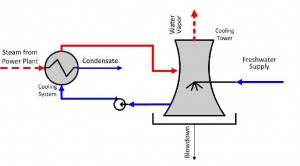

In open-loop cooling, (see figure), large volumes of water are withdrawn from a water source (reservoir, lake or river), and flows through the heat exchanger to condense steam in a single pass before most is returned to the source. Open-loop cooling uses 40 to 80 times more water than other technologies but returns most of the water so it isn’t “consumed.” However, this large water withdrawal can have severe impacts on nearby users, as it will not be available for other needs. Additionally, water intake structures can kill fish and the elevated temperature of the return water can also create problems.

Closed-loop cooling (see figure) is an alternative to open-loop cooling. Instead of withdrawing water and using it once, closed-loop cooling recycles water for additional steam condensation. There is also dry or air cooling which requires little to no water because it uses air instead of water to cool.

The best technology depends on the location

With all of these options, which cooling technology is the best one to use? The answer is location, location, location. Each one has benefits and drawbacks, but those drawbacks can seem larger in certain situations.

For example, open-loop cooling would not be suitable near a water source with a large fish population or where other nearby water users also depending on the supply. However, it might be suitable for a plant with a cooling reservoir and limited wildlife. Similarly, dry cooling often makes the most sense in arid areas, where water is at a premium.

The best policy for plant planning would be one that requires a water availability study when the air permit application process begins. This study should list other water users, including the fish and wildlife, and define the proposed water source for the lifetime of the plant. Decisions on cooling technologies should be made after evaluating all these factors and involving the community. This helps ensure the needs of all users and plant security.

One thing is certain, with today’s water management challenges, water can no longer be an afterthought to locating and building power plants.