The Underlying Issue Is Freedom of Religion

By Roy L Hales & Robert Lundahl

In a remote corner of the Mojave Desert, 15 miles from Las Vegas, stands the expansive Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System. Occupying 5 square miles, the facility seems to swallow up a stunning expanse of desert including animals, plants and now, spiritual and cultural resources.

Native elders filed a suit against the Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, and the Department of Energy in 2010, for failure to properly consult with the tribes in regard to the development of six renewable projects.

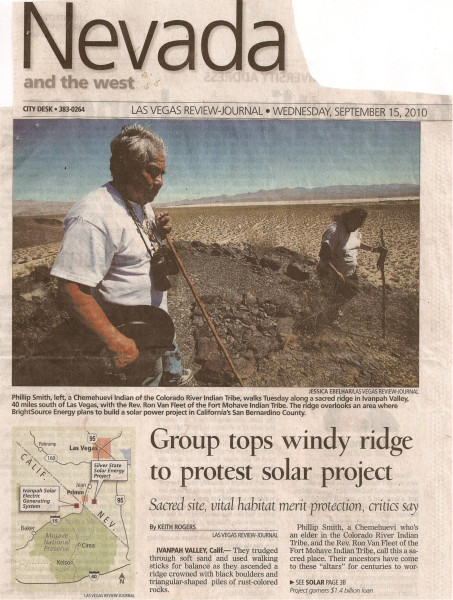

Litigants Alfredo Figueroa (Yaqui/Chemehuevi), Phillip Smith (Chemehuevi), and Reverend Ron Van Fleet (Mojave) complain that the government and the companies involved have lent a deaf ear to their concerns, which has brought a new level of anxiety and spiritual pain to people who have long felt their voices muffled in the face of commercial development by others.

Mojave elder Reverend Ron Van Fleet said the rituals he has performed at a sacred site within Ivanpah’s enclosure cannot be meaningfully replicated, in accordance with his tradition and values, at any other location.

The fence around Ivanpah has become a testimony to the extent Native American spiritual beliefs are under attack by the siting of utility scale solar plants in the desert.

On April 10, California’s 9th Circuit Court of Appeals heard an appeal. The immediate question was access; the underlying issue is freedom of religion.

Ivanpah sits astride the ancient Salt Song trail of the Paiutes and Chemehuevi peoples. The sacred site within its’ enclosure is one of hundreds along the trail.

These sites, akin to temples, are sometimes visited in Spirit Runs, which can last for weeks. Participants will run all day, stopping at these sites for a particular view of the Clark Mountains. Or to be in a particular spot when the sun rises. Only Native Americans can no longer visit the site within Ivanpah.

The Department of the Interior’s lawyer claims there is nothing of significance at Ivanpah, “unless every point along the trail, or several points along the (Salt Song) trail are of such significance.”

(You can listen to a audio recording of this hearing @ http://cdn.ca9.

There is also a controversy brewing at Metamorphic Hill, which overlooks Ivanpah. According to Lloyd Gunn of the Sierra Club Desert Committee, a transmission line is being built close to another sacred site.

Gunn took part in the Spirit Run up Metamorphic Hill that is shown in Robert Lundahl’s documentary Who Are My People? There is a still of them worshipping in front of two ancient triangles, composed of hundreds of rocks, at the top of this page. Chemehuevi Cultural Monitor Alfredo Figueroa is shown with his hands raised up, as he gives thanks to the Creator.

The white triangle is filled with quartz. Figueroa said, among other things, it is a geo-locator pointing to Spirit Mountain in the Southeast. Spirit Mountain is called Avi-Kwame in the Mojave language. In the Uto-Aztecan worldview it is referred to as Tlalocan.

It is an altar with prayer rocks, that Gunn believes is hundreds if not thousands of years old. The black arrow, or triangle, points to the Clark Mountains to the Northwest, the location of hot springs. Figueroa says the Salt Song Trail connects the two.

“I called BLM at Needles, and talked to Mike Ahrens, the field manager. He directed me to his archaeologist and I was told there was no such thing as a sacred site out there,” said Gunn.

He asked the archaeologist, “Why are you pretending it doesn’t exist?”

When the ECOreport phoned Needles, Mike Ahrens admitted he does not know where the site is. He never-the-less insisted it is outside the footprint of the project. Ahrens said he has heard reports “from non-Native Americans,” but no Native Americans have mentioned it during the year he has been at Needles.

However a photograph on the September 15, 2010, Las Vegas Review-Journal depicts Chemehuevi elder Phillip Smith and Mojave elder Rev. Ron Van Fleet beside one of the triangles.

“We’re reaching out to Phil Smith because we’d like to get his take on this. If the Chemehuevi share this concern then we want to address it,” said Ahrens.

There have been many incidents in the Native American struggle to exercise the same rights everyone is guaranteed under the First Amendment.

A scene in Who Are My People? documents the German company Solar Millennium bulldozed two of the ancient geoglyphs at Blythe. One of them, the True North Geoglyph, was 50 feet long.

The Ocotillo Wind Project was built despite tribal opposition, on land the the California Native American Heritage Commission recognizes as a sacred Native American cultural landscape and burial ground. The Quechan name for this area is the “Valley of Death.”

In the promo for Who Are My People?, Preston Arrow-weed (Quechan/Kumeyaay) said these actions weren’t taking away his culture, “They’re destroying it!”

The film documents a BLM official named Lyn Ensler admitting she could not remember which tribes she had contacted or “which tribes went to which meetings.”

(For a limited time only, the ECOreport offers unrestricted access to Who Are My People? as a screener.)

Alfredo Figueroa said none of the Quechan and Mojave elders were given advance written notice of the meeting at Blythe City Hall, on July 23, 2013. If he hadn’t been tipped off the day before, they would not have been present at a scoping meeting discussing the solar projects at Blythe and McCoy.

“This is the most sacred site of the world and it was the worst location for the solar company to place these massive solar projects. It is where the spirit of El Tosco descends down from Tamoanchan and is the center of the Creation story,” said Figueroa.

They did not stop Brightsource from building Ivanpah, but Native Americans still want access to their sacred site within the facility’s fence. They also want the Government to consult with them before destroying markers in the future.

The judge is not expected to announce his decision for months. When he does, it will most likely be a decision regarding access to Ivanpah. The real issue, an apparent contradiction of religious freedoms guaranteed in the First Amendment of the Constitution, might not even be mentioned.

Some say the level of racial and cultural antipathy towards Native Americans seems to be so deeply ingrained and so vicious, a result of competing value systems that often hold land as sacred, that the presumption of the government may well be that the rights accorded to every other individual and group do not apply.

For many, this dichotomy seems to be fine in practice. Or is it?

Image at top of page: PHOTO: LUNDAHL “Who Are My People?” Documentary Film ©2015 Robert Lundahl & Assoc.