Ebola is one of the most frightening viruses of modern times and the recent outbreak in West Africa sparked a worldwide effort to contain it. Though it is far from under control in much of the region, there is a glimmer of hope as the World Health Organization (WHO) has announced that in trials, a vaccine called VSV-EBOV has proven to be 100 percent effective in protecting individuals.

One of the paradoxes of the recent Ebola outbreak is that it was both a human tragedy and a blessing in disguise. Though previous outbreaks had occurred going back a generation, these were so brief and involved so few people that it wasn't possible for doctors to develop an effective vaccine suitable for human use. However, the 2014 outbreak, which tragically killed over 10,000 people, also provided an opportunity to conduct trials of new vaccines to combat the virus.

The WHO announced on Friday that the trials that began on March 23, 2015 were conducted by a partnership led by the Guinean authorities, WHO, Médecins sans Frontières, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. It involved giving individuals single doses of the VSV-EBOV vaccine with, to date, 100 patients and over 4,000 close contacts having been vaccinated.

Based on the vesicular stomatitis virus, VSV-EBOV is one of eight vaccines under development. Created by the Public Health Agency of Canada, it was further developed and produced under license by NewLink Genetics and Merck & Co. The health organization says that the Guinea Phase III efficacy vaccine trial used an approach called "ring" vaccination, which is similar to the approach used in eradicating smallpox in the 1970s.

"The 'ring' vaccination method adopted for the vaccine trial is based on the smallpox eradication strategy," says John-Arne Røttingen, Director of the Division of Infectious Disease Control at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and Chair of the Study Steering Group. "The premise is that by vaccinating all people who have come into contact with an infected person you create a protective 'ring' and stop the virus from spreading further. This strategy has helped us to follow the dispersed epidemic in Guinea, and will provide a way to continue this as a public health intervention in trial mode."

For the trials, half of the participants were vaccinated three weeks after identification of an infected patient. This was to provide a control group without having to use placebos, which would have been unethical when dealing with such a deadly disease. The delay creates a randomized group while ensuring that all people in contact with the infected patient are protected.

According to the WHO, the Guinean national regulatory authority and ethics review committee has given the green light for trials to continue. The next phase will concentrate on proving "herd immunity" for protecting entire populations. In the meantime, all people in the trials will receive doses immediately. The trials will also include aid workers, children aged 13 and above, and may be expanded to include children as young as six

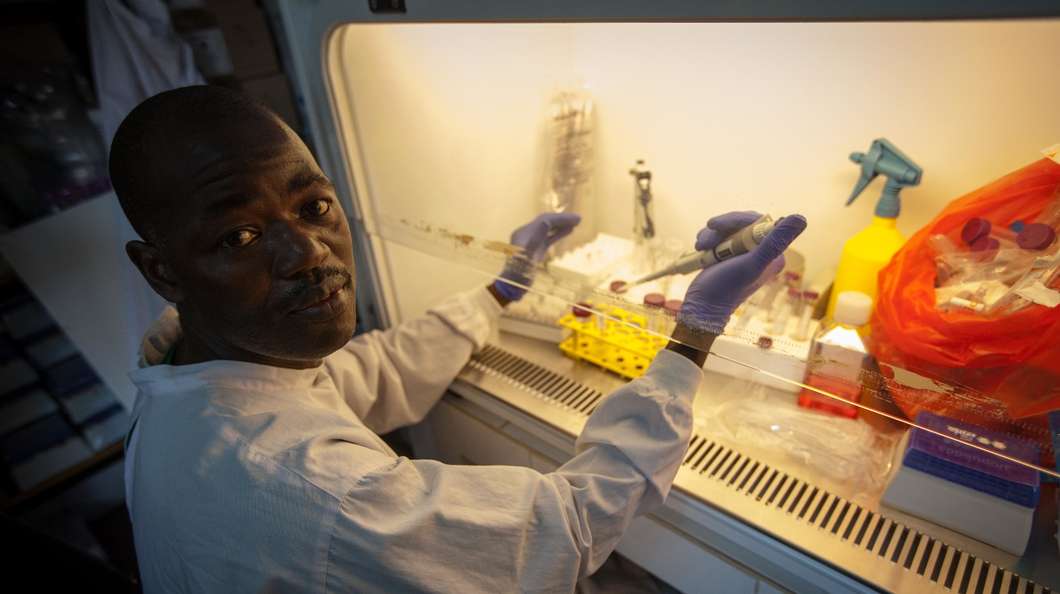

"In parallel with the ring vaccination, we are also conducting a trial of the same vaccine on frontline workers," says Bertrand Draguez, Medical Director at Médecins sans Frontières. "These people have worked tirelessly and put their lives at risk every day to take care of sick people. If the vaccine is effective, then we are already protecting them from the virus. With such high efficacy, all affected countries should immediately start and multiply ring vaccinations to break chains of transmission and vaccinate all frontline workers to protect them."

The results of the trial were published in The Lancet.

Source: WHO