The Big Fracking Question: Is Drinking Water At Risk?

By Blaise Ekechukwu, graduate student and Jafar Soltan, P. Eng., associate professor of chemical engineering, University of Saskatchewan

Understanding the impacts of hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) on source water, in both quantity and quality, is of vital importance to industry, the economy, and society. The latest research on the subject is presented, along with possible solutions to help overcome known and potential problems.

In an attempt to proffer a solution to the global high demand for energy, energy production has been increased with the introduction of hydraulic fracturing for accessing low-permeability, organicrich shale formations and tight gas sands, with the resultant increase in natural gas production. These benefits of hydraulic fracturing have led to exemption of flow-back fluids from regulatory bodies in the U.S. and mandates within the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) and the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). Hydraulic fracturing, a non-conventional method of drilling, is believed to have negative effects on source water. This article addresses the purported impacts of hydraulic fracturing processes on source water, the mechanism of the contamination of source water, the possible solutions to these negative impacts of hydraulic fracturing, and the need for further investigation and scientific research on the behavior of hydraulic fracturing fluids with the aim of identifying potential risks to source water.

Hydraulic fracturing functions as a double-edged sword: It permits the extraction of oil and natural gas in an unconventional reservoir with low permeability but also carries significant environmental risk. To summarize the practice, hydraulic fracturing is a wellstimulation technique used for the extraction of oil and natural gas in unconventional reservoirs with low permeability, such as shale, coal beds, and tight sands1. To understand the environmental risks associated with hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, a brief overview of the fracking water cycle is below.

Hydraulic Fracturing Water Cycle

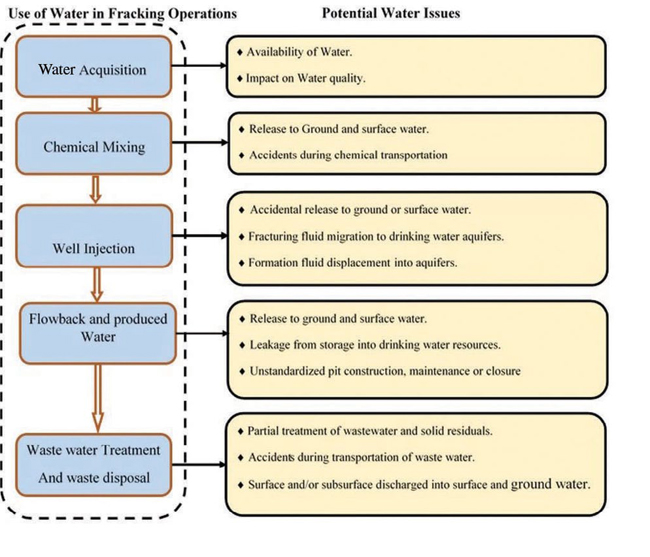

The hydraulic water cycle is divided into five stages2,

as shown in Figure 1.

- Water acquisition

- Chemical mixing

- Well injection

- Flow-back and produced water

- Wastewater treatment and waste disposal

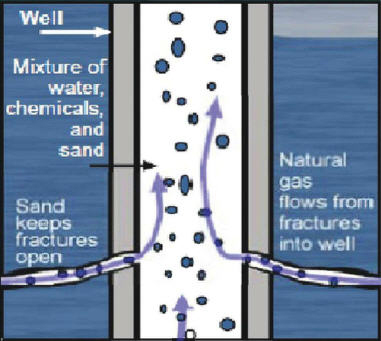

The large volume of water needed for fracking is transported to the site, followed by the mixing of the water with chemicals and sand (proppant) at the well site. The well injection process as shown in Figure 2 involves the injection of engineered fluids or chemicals and granular materials into the well at high pressure between 15 to 100 psi (pound force per square inch) to shatter petroleum reserves and stimulate the flow of oil or natural gas to the surface1. After the fracturing of the well, the injection fluids are forced out under pressure. The flow-back fluids are either re-injected to Class II injection wells, recycled at the site, or transported to wastewater treatment facilities2.

Regardless of the high resource potential and economic benefits of the process, there is growing concern about the negative potential environmental impacts and human health implications, which may include groundwater and surface water contamination, land destruction, air pollution, geologic disruption, greenhouse emissions, and radiation1,3. The risk of hydraulic fracturing is more focused on its impact on source water and the potential contamination route, which would be the area of focus in this report. Although it is believed that hydraulic fracturing poses a risk to water resources, the extent of the risk and/ or damage already inflicted are yet to be properly assessed due to insufficient scientific information and understanding of the mode of the risk4.

Potential Risks Of Hydraulic Fracturing To Source Water

The risks associated with hydraulic fracturing to source water

include:

Water scarcity: Despite the consumption of high volumes of water, the total volume consumed is relatively small compared to the existing water resources in Canada4. Also, in the U.S., the quantity of water withdrawn for hydraulic fracturing is only about one percent of the total freshwater when compared to usage by thermoelectric-power generation, which consumes approximately 40 percent of the total freshwater withdrawal6,7. However, in areas with dry climates like Texas, Colorado, and California, the use of water for hydraulic fracturing could compete with other water needs, leading to local water shortages which subsequently degrade water quality.

Stray gas contamination: Stray gas (fugitive hydrocarbon gases) contaminates shallow aquifers, leading to salinization of shallow groundwater from hydraulic fracturing fluids through leaking shale gas3.

Spills and leaks: Surface leaks and spills of flow-back and produced water through insufficient pit lining, onsite spills, overflow, or breaching of surface pits during shale gas operations mainly occur near drilling locations3. They contaminate soil, surface water, and shallow groundwater.

Figure 1. Water use and potential concerns in hydraulic fracturing operations (adapted from EPA, 20112)

Toxic and radioactive accumulation: The disposal of treated flow-back and produced wastewater containing naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORM) may lead to accumulation of radium in stream sediments downstream of the disposal sites5. The radiation poses environmental and health risks.

Insufficient treatment and unauthorized discharge of untreated water from shale gas operations: This was revealed by joint U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) studies, as in the case of Acorn Fork Creek in southern Kentucky in May and June 2007, which linked the deaths of aquatic species to the disposal of untreated wastewater10. It was also observed that effluent discharges from treatment sites in Pavillion, WY were known for their high salinity levels (120,000 mg/L), high toxic metals (strontium and barium) and radioactive elements (radium isotopes), and organic makeup (benzene and toluene)11.

Figure 1 presents the hydraulic fracturing water cycle and the potential source water issues.

Potential Threat To Surface Water Sources

Surface water contamination from hydraulic fracturing fluid may

occur during treatment, storage, or disposal processes when there

are accidental spills, leakages, or leaching into the nearby surface

water1. Hydraulic fracturing wastewater also poses a

threat to surface water because it contains other chemicals (metals,

dissolved solids, organics, and nucleotides other than the fracking

additives) that could overflow, spill, or leach into the groundwater

and contaminate nearby rivers or streams1. When they are

treated, the total dissolved solids (TDS) remain high, and the

remaining salts are used as road salts, which enter surface waters.

Potential Threat To Groundwater Sources

The anticipated groundwater contamination mechanism is related to

flow-back waters and hydraulic fracturing fluids, which could lead

to upward leakage of natural gas along well casings or natural

fractures that allow entry of gas into fresh water aquifers or into

the atmosphere3. Further studies are needed to verify

this claim. In addition, the natural geochemical processes allow the

gas to be assimilated by the fresh water aquifer, which reacts and

may liberate natural contaminants such as metals and hydrogen

sulfide, leading to degradation in water quality4. This

claim has not been substantiated, as there have not been any

baseline monitoring and assessment of the assimilation capacity in

potential shale gas regions to ascertain the release of these

contaminants4. Other proposed possible mechanisms include:

- Oxidation of fugitive methane through sulfate-reducing bacteria. This initiates the reductive dissolution of oxides in the aquifer, which may mobilize redoxsensitive elements (manganese, iron, or arsenic) and reduce the quality of groundwater3.

- High concentration of halogens in saline waters could lead to the formation of toxic trihalomethanes (THM), though there is no data related to stray gas contamination from shale gas wells3.

- There is evidence of cases of naturally occurring saline groundwater in areas of shale gas development in the Appalachian Basin, which makes the quantification of contamination from antropogenic sources of groundwater pollution difficult3.

Figure 2. The hydraulic fracturing process (adapted from EPA , 20112)

Possible Solutions

- Previous studies show that stray gas contamination happens within less than 1 km (3,281 ft.)12,13 of the well site. Based on this, enforcing a safe zone of 1 km between an existing drinking water well and proposed shale gas sites is reasonable.

- The impact of natural gas irrespective of naturally occurring, or leakage from, shale gas could be addressed by mandatory baseline monitoring using modern modeling tools for the characterization of the chemical and isotopic compositions in areas of shale gas development3.

- Full disclosure of the hydraulic fracturing chemicals used for open and scientific discussion and investigations3 is recommended.

- A zero discharge policy on untreated wastewater and developing adequate treatment technologies will prevent surface contamination3. In addition, developing remediation technologies for adequate treatment and safe disposal of wastewater will alleviate environmental issues associated with hydraulic fracturing processes3.

- The water scarcity issue could be remedied using the

highlighted means:

- By good water management practices coupled with improved characterization and monitoring of the drainage basin in the region of shale gas development, the challenge of water use could be avoided4.

- The use of saline, mineralized, and other forms of marginal water or other types of liquid-like gel for hydraulic fracturing will limit the use of fresh water resources for shale gas development3. For instance, in the Horn River Basin of British Columbia, Canada, saline groundwater of TDS (30,000 mg/L) is treated, which removes hydrogen sulfide and other gases, and the treated water is used for hydraulic fracturing9.

- The use of acid mine drainage (AMD) for hydraulic fracturing could mitigate the AMD discharge, which could be blended with flow-back waters, leading to the formation of Sr-barite salts that neutralize some of the contaminants in both fluids8.

- Withdrawing water during the peak period and storing until it is needed4.

- Recycling of flow-back water.

Conclusion

With the debate on the negative impacts of hydraulic fracturing to

environment and human health, there is need for further research on

the behavioral activities of hydraulic fracturing

chemicals/additives and the mechanism of contamination of source

water. Such research would identify the potential risks associated

with hydraulic fracturing processes and provide means of mitigating

the contamination of source water.

References

1. McBroom, M. (2013). Effects of induced hydraulic fracturing

on the environment: commercial demands vs. water, wildlife, and

human ecosystems. Oakwood, Canada: Apple Academic Press. Retrieved

from http://www.ebrary.com on September 10, 2014.

2. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2011). Plan to study the

potential impacts of hydraulic fracturing on drinking water

resources; EPA/600/R-11/122/November; U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency: Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

3. Vengosh, A., Jackson, R. B., Warner, N., Darrah, T. H., and

Kondash, A. (2014). A critical review of the risks to water

resources from unconventional shale gas development and hydraulic

fracturing in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology

[0013-936X] Vengosh, Avner 48 (15), 8334-8348.

4. Expert Panel on Harnessing Science and Technology to Understand

the Environmental Impacts of Shale Gas Extraction. (2014).

Environmental impact of shale gas extraction in Canada. Retrieved

from http://www.ebrary. com on September 11, 2014.

5. Warner, N. R., Christie, C. A., Jackson, R. B., and Vengosh, A.

(2013). Impacts of shale gas wastewater disposal on water quality in

western Pennsylvania. Environmental Science Technology, 47 (20),

11849-11857.

6. Nicot, J. P., Scanlon, B. R. (2012) Water use for shale-gas

production in Texas, U.S. Environmental Science & Technology, 46

(6), 3580−3586.

7. Murray, K. E. (2013). State-scale perspective on water use and

production associated with oil and gas operations, Oklahoma, U.S.

Environmental Science & Technology, 47 (9), 4918−4925.

8. Kondash, A. J., Warner, N. R., Lahav, O., and Vengosh, A. (2014).

Radium and barium removal through blending hydraulic fracturing

fluids with acid mine drainage. Environmental Science & Technology,

48 (2), 1334−1342.

9. Rivard, C., Lavoie, D., Lefebvre, R., Séjourné, S., Lamontagne,

C., and Duchesne, M. (2014). An overview of Canadian shale gas

production and environmental concerns. International Journal of Coal

Geology, 126(0), 64-76.

10. Papoulias, D. M., and Velasco, A. L. (2013) Histopathological

analysis of fish from Acorn Fork Creek, Kentucky exposed to

hydraulic fracturing fluid releases. Southeastern Naturalist,

12,90−111.

11. Ferrar, K.J., Michanowicz, D.R., Christen, C.L., Mulcahy, N.,

Malone, S.L., and Sharma, R.K. (2013) Assessment of effluent

contaminants from three facilities discharging Marcellus Shale

wastewater to surface waters in Pennsylvania. Environmental Science

& Technology, 47 (7), 3472−3481.

12. Osborn, S.G., Vengosh, A., Warner, N.R., and Jackson, R.B.

(2011). Methane contamination of drinking water accompanying

gas-well drilling and hydraulic fracturing. Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences of U.S.A., 108, 8172−8176.

13. Jackson, R.B., Vengosh, A., Darrah, T.H., Warner, N.R., Down,

A., Poreda, R.J., Osborn, S.G., Zhao, K., and Karr, J.D. (2013).

Increased stray gas abundance in a subset of drinking water wells

near Marcellus shale gas extraction. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences of U.S.A., 110 (28), 11250−11255.

Blaise Ekechukwu is a graduate student at the University of

Saskatchewan (Saskatoon, Canada), pursuing his master of engineering

degree in the department of chemical and biological engineering. His

interest is in industrial waste treatment systems and engineering

process design.

Jafar Soltan, P. Eng., is an associate professor of chemical

engineering in the department of chemical and biological engineering

at the University of Saskatchewan. An important focus of his

research is the development of catalysts to enhance the reaction of

ozone with emerging pollutants in water.

Image credit: "Fracking," humbert15 © 2013, used under an

Attribution 2.0 Generic license:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Copyright © 1996 - 2014, VertMarkets, Inc. All rights reserved. To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.wateronline.com

http://www.wateronline.com/doc/the-big-fracking-question-is-drinking-water-at-risk-0001