Solar flare

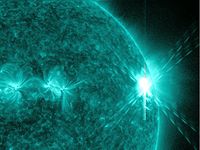

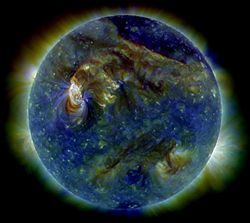

A solar flare is a sudden flash of brightness observed over the Sun's surface or the solar limb, which is interpreted as a large energy release of up to 6 × 1025 joules of energy (about a sixth of the total energy output of the Sun each second or 160,000,000,000 megatons of TNT equivalent, over 25,000 times more energy than released from the impact of Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 with Jupiter). They are often, but not always, followed by a colossal coronal mass ejection.[1] The flare ejects clouds of electrons, ions, and atoms through the corona of the sun into space. These clouds typically reach Earth a day or two after the event.[2] The term is also used to refer to similar phenomena in other stars, where the term stellar flare applies.

Solar flares affect all layers of the solar atmosphere (photosphere, chromosphere, and corona), when the plasma medium is heated to tens of millions of kelvin, while the electrons, protons, and heavier ions are accelerated to near the speed of light. They produce radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum at all wavelengths, from radio waves to gamma rays, although most of the energy is spread over frequencies outside the visual range and for this reason the majority of the flares are not visible to the naked eye and must be observed with special instruments. Flares occur in active regions around sunspots, where intense magnetic fields penetrate the photosphere to link the corona to the solar interior. Flares are powered by the sudden (timescales of minutes to tens of minutes) release of magnetic energy stored in the corona. The same energy releases may produce coronal mass ejections (CME), although the relation between CMEs and flares is still not well established.

X-rays and UV radiation emitted by solar flares can affect Earth's ionosphere and disrupt long-range radio communications. Direct radio emission at decimetric wavelengths may disturb the operation of radars and other devices that use those frequencies.

Solar flares were first observed on the Sun by Richard Christopher Carrington and independently by Richard Hodgson in 1859[3] as localized visible brightenings of small areas within a sunspot group. Stellar flares can be inferred by looking at the lightcurves produced from the telescope or satellite data of variety of other stars.

The frequency of occurrence of solar flares varies, from several per day when the Sun is particularly "active" to less than one every week when the Sun is "quiet", following the 11-year cycle (the solar cycle). Large flares are less frequent than smaller ones.

On July 23, 2012, a massive, and potentially damaging, solar superstorm (solar flare, coronal mass ejection, solar EMP) barely missed Earth, according to NASA.[4][5] There is an estimated 12% chance of a similar event occurring between 2012 and 2022.[4]

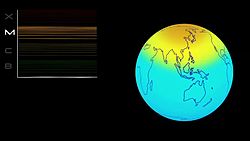

Classification

Solar flares are classified as A, B, C, M or X according to the peak flux (in watts per square metre, W/m2) of 100 to 800 picometre X-rays near Earth, as measured on the GOES spacecraft.

| Classification | Peak Flux Range at 100-800 picometre |

|---|---|

| (Watts/square metre) | |

| A | < 10−7 |

| B | 10−7 - 10−6 |

| C | 10−6 - 10−5 |

| M | 10−5 - 10−4 |

| X | 10−4 - 10−3 |

| Z[citation needed] | > 10−3 |

Within a class there is a linear scale from 1 to 9.n (apart from X), so an X2 flare is twice as powerful as an X1 flare, and is four times more powerful than an M5 flare. X class flares up to at least X28 have been recorded (see below).

However, the extreme event in 1859 is theorised to have been well over X40 so a Z class designation is possible.

H-alpha classification

An earlier flare classification is based on Hα spectral observations. The scheme uses both the intensity and emitting surface. The classification in intensity is qualitative, referring to the flares as: (f)aint, (n)ormal or (b)rilliant. The emitting surface is measured in terms of millionths of the hemisphere and is described below. (The total hemisphere area AH = 6.2 × 1012 km2.)

| Classification | Corrected Area |

|---|---|

| [millionths of hemisphere] | |

| S | < 100 |

| 1 | 100 - 250 |

| 2 | 250 - 600 |

| 3 | 600 - 1200 |

| 4 | > 1200 |

A flare then is classified taking S or a number that represents its size and a letter that represents its peak intensity, v.g.: Sn is a normal subflare.[8]

Hazards

Solar flares strongly influence the local space weather in the vicinity of the Earth. They can produce streams of highly energetic particles in the solar wind, known as a solar proton event. These particles can impact the Earth's magnetosphere (see main article at geomagnetic storm), and present radiation hazards to spacecraft and astronauts. Additionally, massive solar flares are sometimes accompanied by coronal mass ejections (CMEs) which can trigger geomagnetic storms that have been known to disable satellites and knock out terrestrial electric power grids for extended periods of time.

The soft X-ray flux of X class flares increases the ionization of the upper atmosphere, which can interfere with short-wave radio communication and can heat the outer atmosphere and thus increase the drag on low orbiting satellites, leading to orbital decay. Energetic particles in the magnetosphere contribute to the aurora borealis and aurora australis. Energy in the form of hard x-rays can be damaging to spacecraft electronics and are generally the result of large plasma ejection in the upper chromosphere.

The radiation risks posed by solar flares are a major concern in discussions of a manned mission to Mars, the moon, or other planets. Energetic protons can pass through the human body, causing biochemical damage,[10] presenting a hazard to astronauts during interplanetary travel. Some kind of physical or magnetic shielding would be required to protect the astronauts. Most proton storms take at least two hours from the time of visual detection to reach Earth's orbit. A solar flare on January 20, 2005 released the highest concentration of protons ever directly measured,[11] giving astronauts as little as 15 minutes to reach shelter.