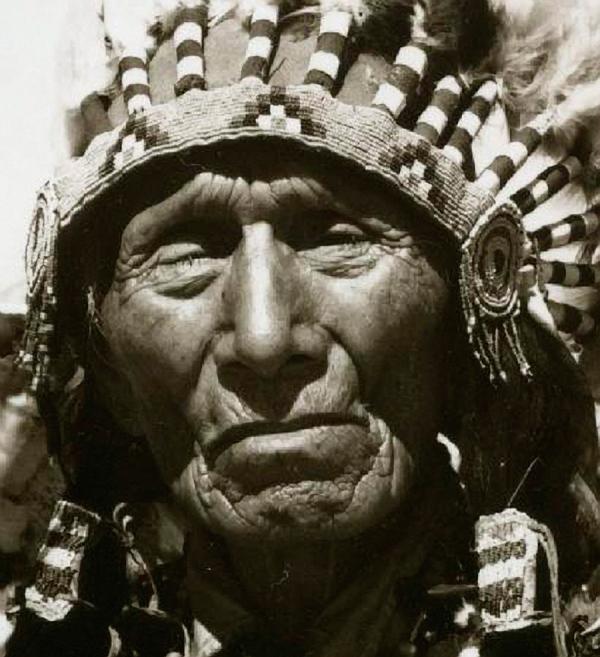

Black Elk, Heȟáka Sápa, (December 1863 – August 19, 1950),

was a wičháša wakȟáŋ (medicine man and holy man) of the

Oglala Lakota (Sioux). He was Heyoka and a second cousin of

Crazy Horse.

Black Elk, wičháša wakȟáŋ, of the Oglala Lakota - A Life In Photos

6/12/15

"The only thing I really believe is the pipe religion."

- Black Elk, near death, to his daughter Lucy Looks

Twice. Pictured here is Black Elk in South Dakota, circa

1900. South Dakota Historical Society via SDPB (South

Dakota Public Broadcasting)

Black Elk was born in Dec. 1863, into a world in strife,

along the Little Powder River (Wyoming), which would be

invaded by European settlers in the next few years. The

Europeans had to compete with the area’s tribes for

scarce resources, leading to Red Cloud's War 1866-1868,

between the U.S. Army and several Indian Tribes.

Pictured here is the signing of The Treaty of Fort

Laramie between William T. Sherman and the Sioux, in a

tent, on April 29, 1868. The Treaty of Fort Laramie

(also called the Sioux Treaty of 1868) was an agreement

between the United States and the Oglala, Miniconjou,

and Brulé bands of Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota, and

Arapaho Nation signed at Fort Laramie in the Wyoming

Territory, guaranteeing to the Lakota ownership of the

Black Hills, and further land and hunting rights in

South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana. The Powder River

Country was to be henceforth closed to all whites. The

treaty ended Red Cloud's War. However the discovery of

gold in the Black Hills in the coming years lead to

violations of the Treaty by prospecting settlers,

culminating in the The Great Sioux War of 1876-77.

Alexander Gardner photo, 1868. (Bettmann/Corbis/AP

Images).

Black Elk grew up in The Black Hills, S.D. (Ȟe Sápa in

Lakota), here seen in an EROS (Earth Resources

Observation Satellite) satellite image on 08-11-2010.

The Black Hills are considered by the Lakota people to

be the Center and heart of everything that is. It is

part of the Lakota people’s creation story. It is a

sacred place. Lt. Col. George Custer’s Black Hills

Expedition of 1874 violated the Fort Laramie Treaty of

1868, and set off a gold rush in the area after Custer

announced her found gold in French Creek, S.D.

13 year-old Black Elk witnessed The Battle of the Greasy

Grass (the Lakota's preferred term), aka. The Battle of

Little Bighorn on June 25–26, 1876. (Bettmann/Corbis/AP

Images)

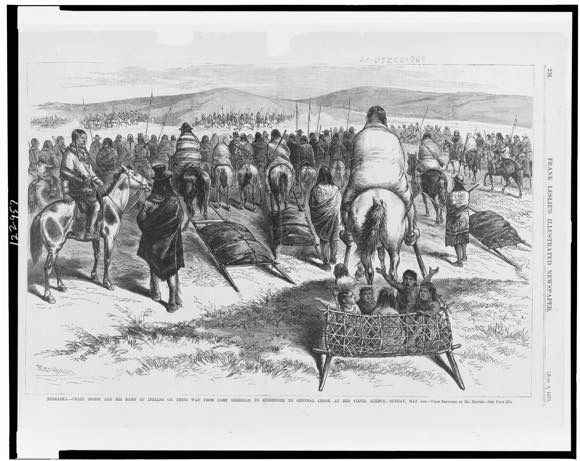

Black Elk was part of his cousin Crazy Horse’s

contingent that escaped capture in the aftermath of The

Great Sioux War 1876-1877, but formally surrendered

after the difficult winter of 1877. Pictured here is a

drawing of Crazy Horse and his band of Indians on their

way from Camp Sheridan to surrender to General Crook at

Red Cloud Agency, Nebraska, Sunday, May 6, 1877. Via

Library of Congress

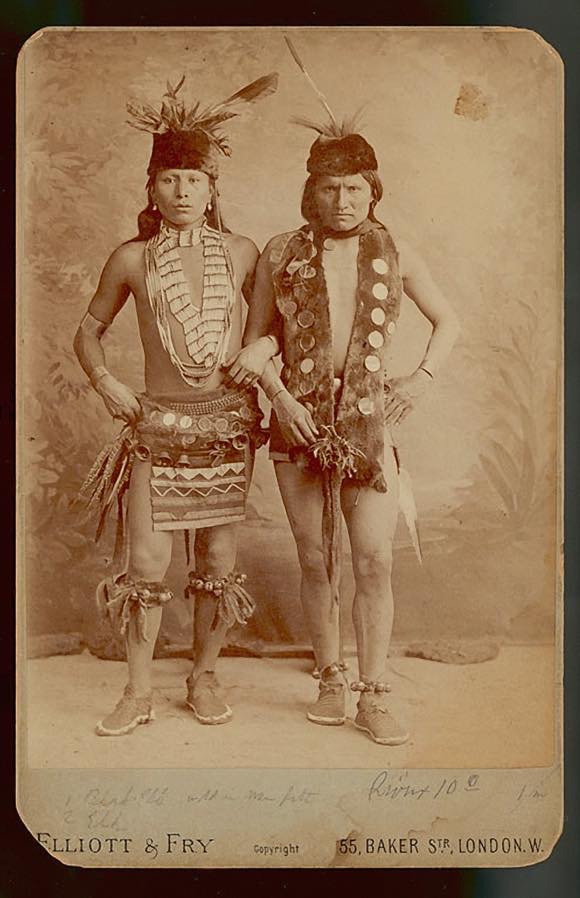

Black Elk and Elk of the Oglala Lakota as grass dancers

touring with the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show, London,

England, 1887. The men are wearing sheep and sleigh

bells; otter fur waist and neck pieces; pheasant feather

bustles at the waist; dentalium shell necklaces; and

bone hairpipes with colored glass beads. Photograph

collected on Pine Ridge Reservation in 1891 by James

Mooney. Courtesy National Anthropological Archives,

Smithsonian Institution

At The Battle Of Wounded Knee on Dec. 29th,1890, Black

Elk on horseback charged soldiers and helped to rescue

some of the wounded. He arrived after Spotted Elk's (Big

Foot's) band of people had been shot and he was grazed

by a bullet to his hip. Pictured here is the terrible

aftermath of the massacre. AP Images.

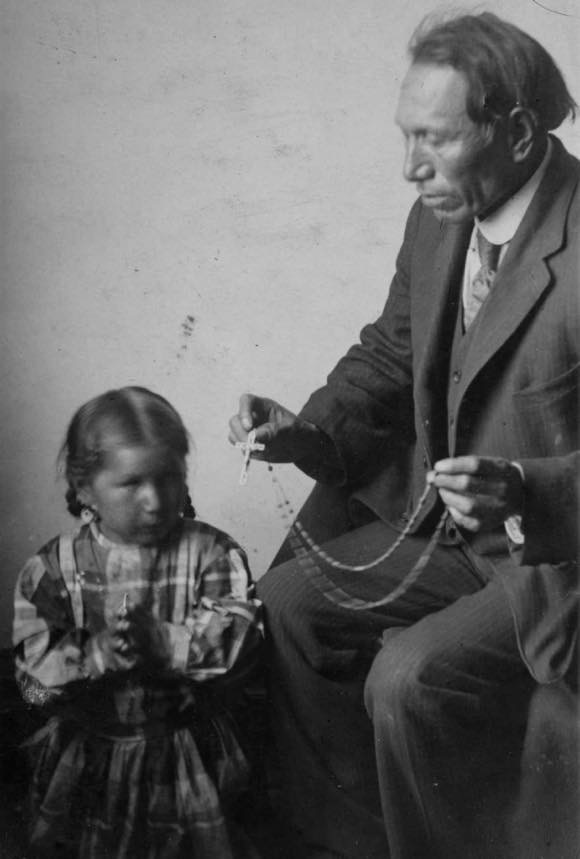

Black Elk married Katie War Bonnet in 1892 on the Pine

Ridge Reservation, and they had three children. Katie

converted to Catholicism, and after her death in 1903,

Black Elk converted to Catholicism in 1904 and took the

first name Nicholas. Pictured here is Nicholas Black Elk

teaching daughter Lucy Looks Twice (born Black Elk) how

to pray the rosary. Published In the land of the Wigwam:

Missionary Notes from the Pine Ridge Mission by Henry

Ignatius Westropp, undated (ca. 1910), p. 13. Marquette

University E-Archives.

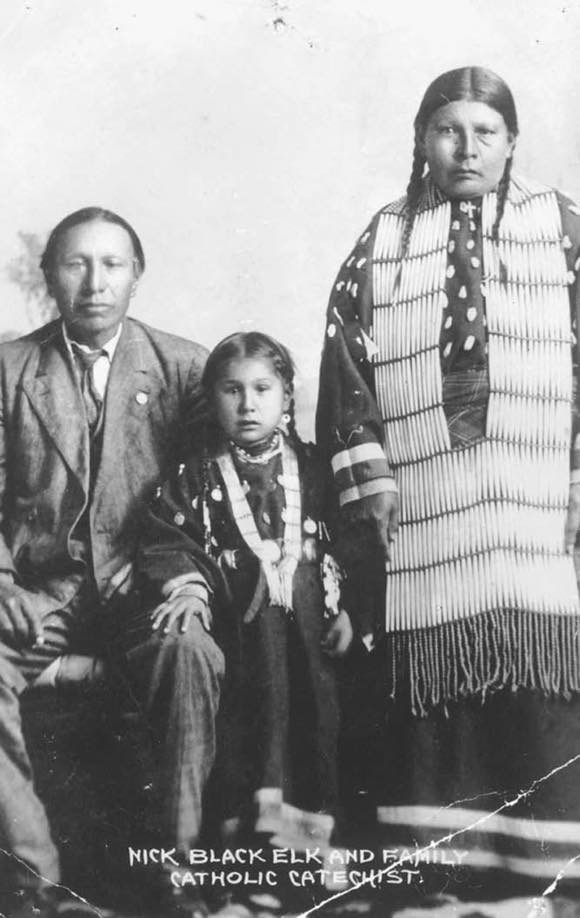

Nick Black Elk, daughter Lucy Black Elk and wife Anna

Brings White, photographed in their home in Manderson,

South Dakota, ca 1910. Black Elk wears a suit, his wife

wears a long dress decorated with elk's teeth and a hair

pipe necklace. Wikipedia

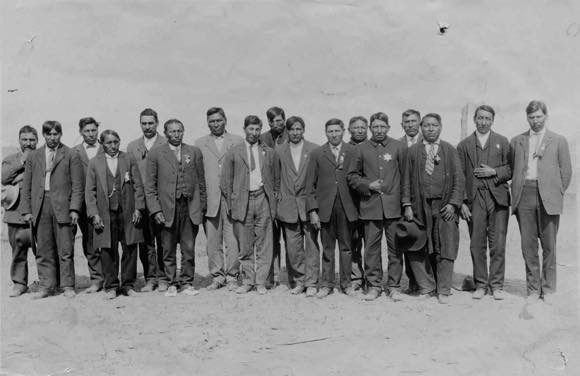

Nick Black Elk 6th from left (wearing moccasins), at The

Cathechists at Catholic Sioux Congress, 1911; published

in The Indian Sentinel, 1(1916). Marquette University

E-Archives

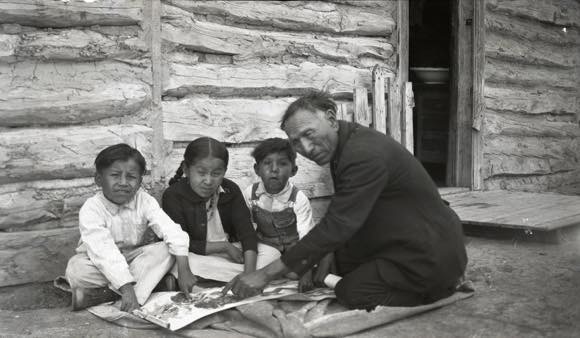

Black Elk, Age ca. 62-63, 1927 or 1928. He taught the

faith with the “Two Roads” picture map with the Good Red

Road (red = Jesus’ blood) and the Black Road of

Difficulties, at Broken Nose cabin, Pine Ridge

Reservation. Marquette University E-Archives

1930-31 Black Elk with his drum and Standing Bear with

Black Elk's pipe; in the foreground a Chief Joseph

blanket. Photograph taken by John G. Neihardt during the

interviews for the book Black Elk Speaks, published in

1932. John G. Neidhart Trust

1930-31 Enid Neihardt, Nick Black Elk, his son Ben Black

Elk, Standing Bear, and John G. Neihardt, during the

interviews for Black Elk Speaks, published in 1932. John

G. Neihardt Trust

Black Elk at a feast given by John G. Neihardt in May

1931, during the interviews for Black Elk Speaks,

published in 1932. John G. Neihardt Trust

![Black Elk returns to pray on Harney Peak, 1931, the site of his “Great Vision,” when he was nine years old. In his vision he saw “the Thunder Beings and taken to the Grandfathers, who represented the six sacred directions of west, east, north, south, above, and below. They took Black Elk to theater of the earth, the central mountain of the world, the axis of the six sacred directions, the point where stillness and movement are together.” [Wikipedia]. Harney Peak, called Hinhan Kaga by the Lakota Sioux, is the highest natural point in South Dakota and the Black Hills. Neidhart.com](1931_black_elk_prays.jpg)

Black Elk returns to pray on Harney Peak, 1931, the site

of his “Great Vision,” when he was nine years old. In

his vision he saw “the Thunder Beings and taken to the

Grandfathers, who represented the six sacred directions

of west, east, north, south, above, and below. They took

Black Elk to theater of the earth, the central mountain

of the world, the axis of the six sacred directions, the

point where stillness and movement are together.”

[Wikipedia]. Harney Peak, called Hinhan Kaga by the

Lakota Sioux, is the highest natural point in South

Dakota and the Black Hills. Neidhart.com

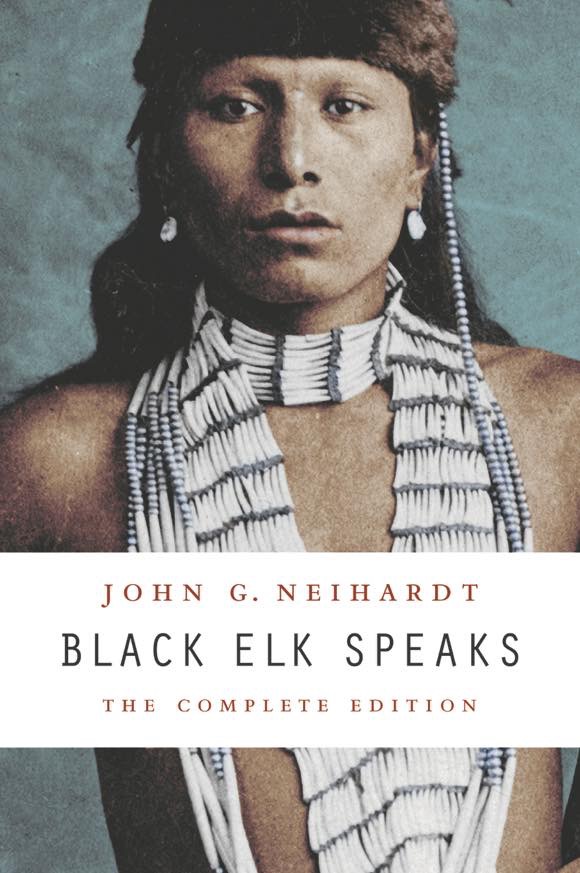

A new edition of "Black Elk Speaks," the 1932 classic by

John G. Neihardt, was published in a “Complete Edition”

in 2014 by the University of Nebraska Press. In it Black

Elk relates his life and visions.

![1937 Nicholas Black Elk in chief's costume. “Beginning in 1934, Black Elk returned to the work that he had done earlier in life with Buffalo Bill – organizing an Indian show in the Black Hills. Unlike the Wild West shows which were used to glorify Indian warfare, Black Elk's show was used primarily to teach tourists about Lakota culture and traditional sacred rituals – including the Sun Dance.” [Wikipedia]](1937_in_chiefs_costume.jpg)

1937 Nicholas Black Elk in chief's costume. “Beginning

in 1934, Black Elk returned to the work that he had done

earlier in life with Buffalo Bill – organizing an Indian

show in the Black Hills. Unlike the Wild West shows

which were used to glorify Indian warfare, Black Elk's

show was used primarily to teach tourists about Lakota

culture and traditional sacred rituals – including the

Sun Dance.” [Wikipedia]

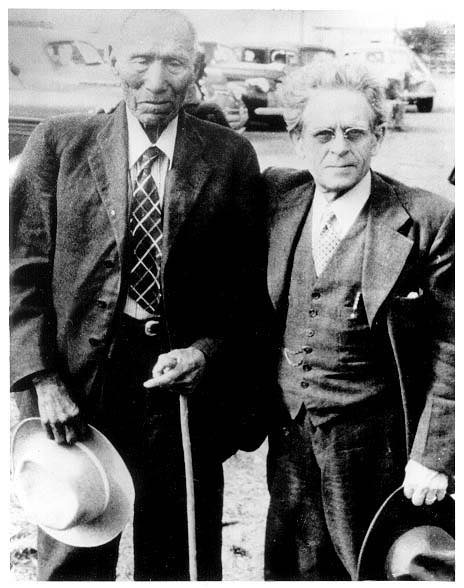

Nicholas Black Elk and John G. Neihardt in 1945. (Black

Elk-Neihardt Park)

Nicholas Black Elk in 1948

1985 "The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk's Teachings Given

to John G. Neihardt, Edited by Raymond J. DeMallie."

These are Transcripts of Neihardt interviews which

reveal greater details on Black Elk’s life and visions

1997 "The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk's Account of the Seven

Rites of the Oglala Sioux. Recorded and Edited by Joseph

Epes Brown." Still more details on Black Elk's life.

Ben Black Elk with pipe at grave of his father, Nicholas

Black Elk. Red Cloud Indian School publicity image,

1970-1971. Marquette University E-Archives.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/06/12/black-elk-wichasa-wakhang-oglala-lakota-life-photos-160706