Fool's Gold: The Story of Jamake Highwater, the Fake Indian Who Won't Die

It's well known, these days, that Iron Eyes Cody—the "crying Indian" from those 1970s commercials—was a fake. And most wrestling fans knew that Chief Jay Strongbow was really Joe Scarpa, an Italian-American from Philadelphia. But that was showbiz—those were actors playing roles. With the scandal surrounding Rachel Dolezal, a former NAACP leader who turned out to be not one bit African American, it's worth recalling the rise and unfortunate persistence of Indian country's biggest intellectual fraud, Jamake Highwater. Alex Jacobs takes us back:

In 1984, Hank Adams (the Native American activist) sent an astounding exposé on the “Indian expert” Jamake Mamake Highwater that we published in the pages of Akwesasne Notes. (Vine Deloria acted as a go-between to get it published and Suzan Harjo did some research.) What Hank Adams had uncovered was that the Native American author (who claimed Blackfoot/Cherokee heritage), a noted intellectual, a recipient of Ford Foundation grants and major publishing contracts, was not a Native American at all, but a writer named J Marks (J, Jay or Jack Marks, born Jackie Marks). Before being a writer, J Marks was a dancer/choreographer in San Francisco where he set up his “Contemporary Dancers Guild/Company/Foundation/School” in the mid to late 1950s. This "World University" or "World Theatre of Dance" was set up as non-profit (illegally) that came under scrutiny when it tried to issue “American college degrees” to its students.

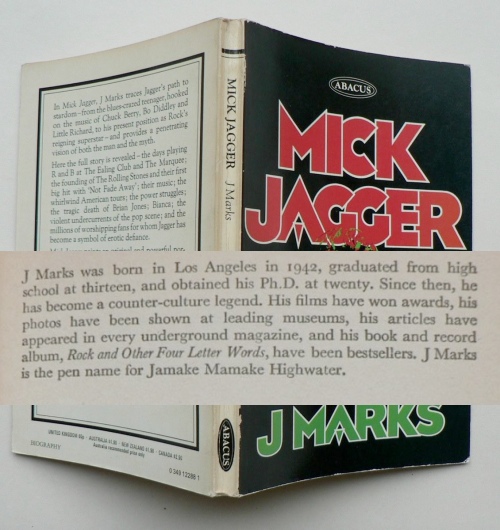

J Marks didn't become American Indian overnight—no, it took him three or four years. Adams pieced it together in a letter to the editors of the L.A. Times and Washington Post in 2001—both papers had reported on the death of noted Native American Jamake Highwater, and Hank couldn't let that stand. The short version goes like this: Marks wrote a book, Rock & Other Four-Letter Words (with Linda Eastman, a photographer later known as Linda McCartney), and recorded an album by the same name, both works were released in 1968. In the book, J Marks is simply J Marks. In the summer of 1969, Marks told a New York Sunday News reporter that his mother was a "full-blooded Cherokee Indian;" then in 1970, Columbia Records issued a 9-page biography, identifying Marks' mother as a Cherokee Indian named Marcia Highwater. Marks authored the lurid 1973 biography Mick Jagger: The Singer, Not the Song, and the book's brief about-the-author page concludes with the line "J Marks is the pen name for Jamake Mamake Highwater." With his Indian name now established, and the seed of a life story tied to his mother "Marcia," Marks the Indian was off and running. The 1975 Fodor's Indian America is credited to Jamake Highwater and makes mention of his mother Marcia.

Although by then, Marcia was no longer Indian, according to a 1974 affidavit. Marcia and Alexander Marks, the document said, were the adoptive parents of J Marks, born Jamake Hightower to a half-Blackfoot mother and Cherokee father. Marks' writing and revising of his story goes on and on, constantly at odds with impartial genealogical records—I'll leave it to you to read Hank Adams' account if you want every gory detail. But as Marks/Highwater was getting his own story straight (or trying, at least) he was also doing his research, making contacts, insinuating himself into Indian circles and any acceptance would end up in his expanding resume, which would boost his credibility to the highest levels of the art world, literary scene, and academia.

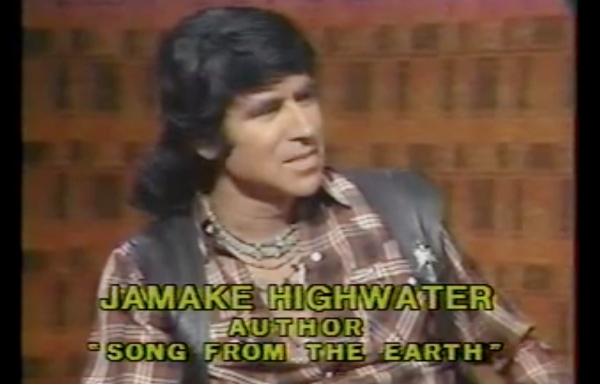

Witness him as the charming con-man in the 1978 video and how unsuspecting white cultural gate-keepers swallow it all hook, line and sinker. Native critics have always said this is the insidious part where imposters like Highwater present themselves as True Intellectuals who have overcome their pathetic Indian past to be able to lift up their own Native culture while informing the dominant American society.

The highlights of Jamake Highwater’s career included his well-reviewed books Song From the Earth: American Indian Painting (1976); Anpao: An American Indian Odyssey (1977), which won Newbery Honors; The Sun, He Dies: A Novel about the End of the Aztec World (1980); and The Primal Mind (1981) book and PBS special. There were not that many Native authors and titles receiving national media attention, so Highwater was able to charm both Native and non-Natives. When researchers could find no “Highwater” among the Blackfoot and Cherokee tribal records, he crossed the border into Canada and got himself “adopted” in a Blackfoot tourist ceremony. Years before, he had pestered his brand new Native contacts into “being invited to join The White Buffalo Council”, which he then placed in his new books’ bio.

Akwesasne Notes published an essay by Highwater, titled “Second-Class Indian” in 1983, in which he related to many other Natives who felt slighted as mixed-race or “some kind of Indian”; this article led Deloria and Adams to approach us with the exposé the next year. Adams' article ruined the CPB/PBS deal that Highwater then had in the works, as the funding was eventually pulled. Highwater phased out the overt Native references in the 90’s, writing about trendy sexuality, gay and mythological themes. The controversy never really died down, just went hot and cold as Highwater travelled the country (he allegedly had offices in Zurich and Istanbul) and dealt with criticisms (“since he was adopted, he knew nothing about his past”). He had a network of high-end supporters who would normally not associate with his critics—angry, unsophisticated Indians. An amazing cultural moment has Jamake Highwater advising Star Trek: Voyager producers on the Native character Chakotay in 1993.

Then it all came out again when the leading newspapers of record, the New York Times, L.A. Times and Washington Post, reported the death of “noted Native American author Jamake M. Highwater on June 3, 2001”. There may have been passing mention of controversy, but these major media outlets had accepted and printed his false name, status, credentials, biography and birth date. He was their Golden Indian Expert, welcomed into the hallowed halls of academia, literature, publishing, PBS-TV, non-profits, he was “The Indian” they preferred to deal with. Just as he was “The Indian” that procured drugs in his rock & roll days. The list of famous people he knew, went to school with, who he conversed with and who supported him is quite extensive: Susan Sontag, Joseph Campbell, Bill Moyers, Karlheinz Stockhousen, Anais Nin, Studs Terkel—yet over time, most admitted to not actually knowing him. One supporter at the Mythos Festival in Philadelphia in 1991, acclaimed anthropologist Ashley Montagu, declared, "I don't see a point in (the criticism) even if he murdered four people and crucified 35 others.” At the same festival, Renee Renouf, a critic for Dance News in San Francisco when J Marks ran the San Francisco Contemporary Dancers in the early '60s, said, "He's the biggest myth of them all."

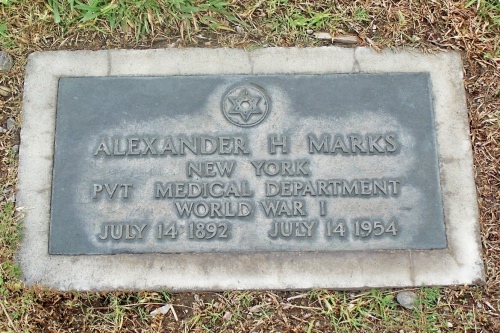

After the death notice, Hank Adams found that Marks’ social security number was wrong, and after it was corrected, he could verify his correct birthdate of Feb. 14, 1931, to mother Martha (Marcia) Turetz and father Alexander Marks (she was born in Russia, he was born in NYC but his parents came from eastern Europe); the father was also listed as an actor and writer in the Hollywood movie industry, which makes sense in defining the real Jackie Marks. That was the name listed on his birth certificate: Jackie Marks. His mother died on September 24, 1984, as Marcia Harrington in Los Angeles. Adams produced a 1959 gravestone of J Marks' father, Alexander Hill Marks, with family-requested military-markings of the Jewish Star of David. Highwater’s death certificate said he died of a heart attack, had other health issues including a decade long diagnosis of AIDS, and was cremated with his ashes spread in the Pacific Ocean.

Adams credits his friend, Joe DeLaCruz, Quinalt activist and President of NCAI in 1984, who said this when he booted Highwater out of the organization:

This person is not an Indian, has no personal or professional experience or academic expertise regarding Indians, has falsely held himself forth as an Indian and an Indian expert, has claimed academic credentials he does not possess and has published under his own name extremely derivative materials from the works of others. Importantly, this person has invented and repeated stereotypic and biased information about Indians.

In “The Golden Indian” article by Hank Adams, his obsessive research made connections with Gregory J. Markopoulos, a reclusive Greek-American experimental filmmaker, whose career happened to share idiosyncrasies with Marks/Highwater. That sensational and uncorroborated detail would leave wiggle room for Jamake Highwater and his supporters to disparage the critics and allow his career to continue another 15 years. To counter the exposé of his past lives, Highwater used his mother to create the idea that he was an adopted Indian child, which rationalized the Marks name and available records.

Hank Adams told me that he eventually did talk (by phone) to Gregory J. Markopoulos, the filmmaker. Markopoulos joked to Adams that “Highwater had plagiarized my life.” The filmmaker had offered to help Adams, but then also let it be known that “it was too late in life to do anything”, and had communicated to his associates to not talk anymore about the issue. Hank and I felt that there was some connection, co-operation or communication between the two men, if not conspiratorial then commiserating. Adams said he met the cult filmmaker Kenneth Anger at a film festival; Anger’s underground films (Scorpio Rising, Hollywood Babylon, Lucifer Rising, the Magick Lantern Cycle), made him among the first openly gay film-makers in Hollywood, tied him to Gregory J. Markopoulos and this connection led to Maya Deren (avant-garde dance/film cult figure) as well as to Marks/Highwater. These were coincidences that came from them associating in the same small circles. Adams recalls sharing a laugh with Anger over Highwater’s death notice—with Hank joking that he also had Kenneth's incorrect death notice from the Village Voice. (Kenneth Anger is alive and well, age 88.)

But it’s all over now. Filmmaker Markopoulos passed away in 1992. Jamake M. Highwater aka J Marks né Jackie Marks died of a heart attack in Los Angeles in 2001. Adams sent me copies of J Marks' birth certificate, and his mother’s (Marcia Turetz) as well. The actions of associates who knew both men in the film and arts community led you to wonder if there was some grand design between the two men, or among the cultural elite. Adams says that people alternately steered him toward and away from the fantastically appealing idea that J Marks and Gregory Markopoulos were actually the same man. Even though, in our imaginations, it was conceivable that such insulated people high above the fray were playing some kind of live cinema fantasy with Native Americans as a backdrop, the plot twist of a dual identity seems far-fetched—even for a faker like J Marks. Highwater's supporters in the arts community continued to invite him to speak and it was one such talk that Adams was able to serve Highwater with papers for a lawsuit. A judge had to dismiss the suit on a technicality; Adams had to pay lawyers’ fees of $25 each.

Gerald Vizenor (Anishinaabe), in his 1988 book, The Trickster of Liberty, has a character Homer Yellow Snow—based on Jamake Highwater—who says to his Native audience: “If you knew who you were, why did you find it so easy to believe in me? … because you want to be white, and no matter what you say in public, you trust whites more than you trust Indians, which is to say, you trust pretend Indians more than real ones.”

Homer Yellow Snow might have gotten his ideas from Vine Deloria, who said this in a speech at the University of Colorado, 1982:

The realities of Indian belief and existence have become so misunderstood and distorted at this point that when a real Indian stands up and speaks the truth at any given moment, he or she is not only unlikely to be believed, but will probably be publicly contradicted and corrected by the citation of some non-Indian and totally inaccurate ‘expert.’ More, young Indians in universities are now being trained to view themselves and their cultures in the terms prescribed by such experts rather than in the traditional terms of the tribal elders. The process automatically sets the members of Indian communities at odds with one another, while outsiders run around picking up the pieces for themselves. In this way, the experts are perfecting a system of self-validation in which all semblance of honesty and accuracy are lost. This is not only a travesty of scholarship, but it is absolutely devastating to Indian societies.

I'll let Hank Adams have the last words on Marks:

This man was the Golden Indian ... he made gold, he made money. It's about stolen voices ... he blocked millions of dollars in funding to real Indian writers. We ended his federal funding and TV contracts, but he's still an Indian author, he sold more books than Vine Deloria, his work is still taught in schools and universities to Native and non-Native students. He died an Indian, his lawyer handles his estate and all its Indian royalties. At least this ends it for sure ... it finishes his career as an Indian and an Indian expert. He's Jack Marks...not Jamake Highwater.

Remember that. He's Jack Marks ... not Jamake Highwater. There never was a Jamake Highwater.

Hank Adams is now completing a study titled: "100 Years of Infamy: The 1915 Assault on the 1870 Mountain Guide Saluskin (Sluiskin) in a Century's Design of Denying Yakama Identity and Access to Treaty Lands for Indian Hunting, Gathering & Ceremonial Sacred Rites in a National Park." Adams describes the story as "an epic scandal involving a crushing identity theft of the highest order as engaged in by government agencies and uncaring accomplices and authors in the academic and professional writing worlds."

Alex Jacobs

Santa Fe NM

June 18, 2015

© 1998 - 2015 Indian Country Today. All Rights Reserved To subscribe or visit go to: http://www.indiancountry.com

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/06/18/fools-gold-story-jamake-highwater-fake-indian-who-wont-die-160773