There Is No Global Warming Hiatus After All

Improved data and better analysis methods find no slowdown in the pace of global temperature rise, NOAA scientists report

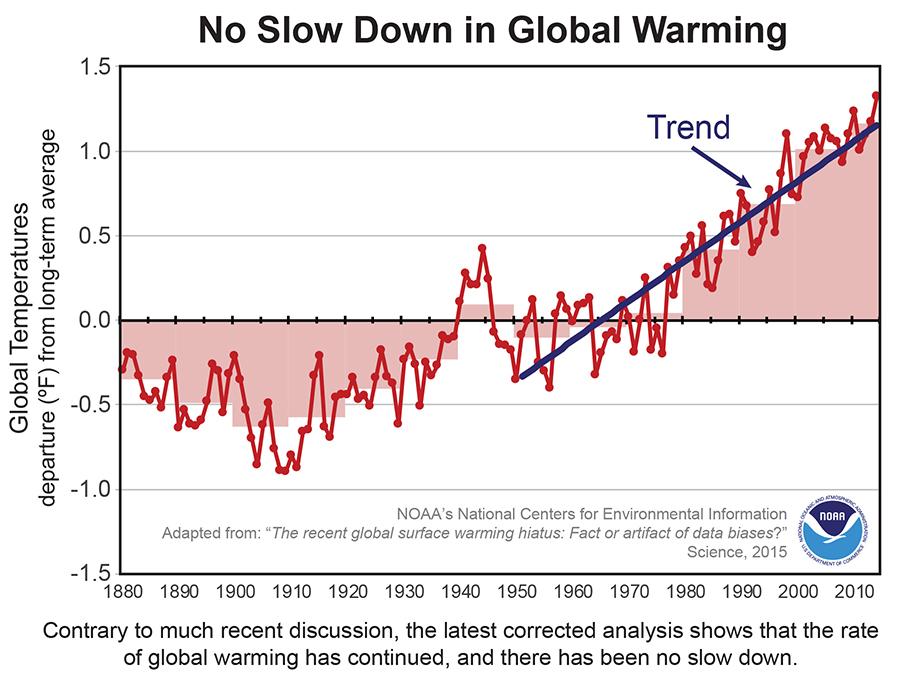

Did global warming take a breather in the early 21st century? Not at all, according to fresh analysis of temperature data that incorporates more information and better methods for parsing historical trends.

In 2013, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released an assessment report that found what appeared to be a halt in the pace of warming. The rate at which surface temperatures rose between 1998 and 2012 was only about a third to a half that seen between 1951 and 2012. This was termed the “hiatus,” and climate change skeptics jumped on the result as evidence that there was no reason to worry.

Earlier this year, though, scientists at NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declared that 2014 was the warmest year since 1880. And now researchers have found that the record temperatures, when combined with better analysis methods, have eliminated any evidence of a pause in global warming.

When the IPCC report was unveiled, scientists tried to figure out where the missing heat had gone. Some thought it may have gotten stored away in the Atlantic or Pacific oceans. Others noted that 1998 was the year of a strong El Niño that caused particularly warm weather around the globe, and using it as the starting point for any trend was problematic.

In their new study, published online today by Science, NOAA scientists address another concern about the temperature data—inconsistencies in how and where it was collected.

“We know that the raw temperature records contain various inconsistencies over the long time history," says co-author Boyin Huang. "Stations may have been moved, sensors are replaced and improved, observation techniques change, and so on.” Before World War II, for instance, most researchers took water temperatures by putting a bucket over the side of a ship. After the war, water temperatures were mostly monitored at engine intakes. Later, more of the water data was collected at buoys instead of from ships.

Each method of collecting data produces slightly different results, similar to what might happen if someone measured their oven temperature with both a mercury and a digital thermometer—the data may be close, but it's not an exact match. Accounting for those differences using established mathematical methods makes the full dataset more consistent.

“These homogenization techniques make it possible to compare temperature data collected from locations around the world and over many decades, improving the accuracy of temperature trend estimates,” Huang says. “The homogenization methods used are carefully documented in journal articles and agency websites that are publicly available.”

image: http://public.media.smithsonianmag.com//filer/c5/a6/c5a6a97f-87d9-435b-bcd4-99176d9cfd52/karl1hr.jpg

There have also been advancements made in where air temperature data is collected on land. Many parts of the Earth, especially in Africa, Asia, South America, the Arctic and the Antarctic, have had few measurement stations. But due to a recent effort, the number of data collection stations has doubled, and coverage has improved.

The new analysis accounts for the changes in data collection on land and sea, and the results show that the rate of global warming between 1998 and 2012 is almost double that reported in the IPCC assessment. Adding 2013 and 2014 to the dataset increases the rate further, and the pace of warming between 2000 and 2014—0.209 degrees Fahrenheit per decade—is nearly the same as that seen in the latter half of the 20th century, the researchers note.

“Science is a cumulative and continuous process, and this is reflected in our continued improvements to the land and ocean surface temperature datasets,” says study co-author Huai-Min Zhang. “The notion of a warming hiatus in the most recent decades, as defined by the [IPCC report], is no longer valid. The global warming rate has been just as fast over the last 15 years as over the previous 50 years.”

Related Content

Read more: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/there-no-global-warming-hiatus-after-all-180955501/#I4Cy2lqRvBwoGbWh.99

Give the gift of Smithsonian magazine for only $12! http://bit.ly/1cGUiGv

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter