Grid Resilience: at what cost -- and how?

By Peter Asmus

Since 1980, the United States has sustained 144 weather disasters whose damage cost reached or exceeded $1 billion, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. The total cost to the nation's economy of these events exceeds $1 trillion. According to the National Climate Assessment, the incidence and severity of extreme weather will continue to increase in the coming years, due largely to climate change. According to the president's U.S. Council of Economic Advisers delaying action on climate change will cost the economy $150 billion annually.

The increasing variability of weather patterns suggests that today's systems of energy provision require a more flexible, dynamic, and sophisticated approach than in the past. California is proving that it is possible to curb emissions without grinding economic activity to a halt. Yet most of its efforts to date have been on reducing causes of climate change, rather than adapting to the reality that extreme weather may be with us for decades to come.

That said, making power grids more resilient has become a primary focus for governments and utilities across the nation. A handful of states on the Eastern seaboard are moving forward with state investments to bolster resilience, but so far, they report mixed results. The states now offering incentives and program support for community resilience microgrids include Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York.

Show Us the Money

The challenge facing technology providers, governments and investors is that there is no established financial value for resilience or metrics to calculate different levels of resilience. While such a value would, in reality, vary from project to project, showing zero value has proven problematic. In the case of the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), undervaluing resilience led to the decision to purchase large amounts of renewable energy at the lowest possible cost. The end result: the majority of these investments cannot be incorporated into microgrids, since they are located off-site, elsewhere on the utility distribution grid, and are therefore vulnerable to grid outages, leaving mission-critical facilities at risk and at the mercy of diesel generators that have notoriously high failure rates.

| CRMs are an emerging market opportunity still fraught with peril in terms of regulatory issues, rising stakeholder expectations and a lack of clear financial business models. |

Connecticut, the first state to enact a law promoting community resilience via microgrids, has taken some radical steps to accelerate adoption of new technology to ensure critical services during emergencies. For example, municipal governments in Connecticut can develop community resilience microgrids that cross public rights of way, a major obstacle in many states to developing any kind of microgrid if a utility is not involved. However, only one microgrid has come online to date, as many municipal governments resiliencewant more reliable grids but don't want to see their electric rates go up. Again, with no financial value assigned to community resilience, the value proposition remains incomplete.

The easiest way to enhance resilience is to place a back-up diesel generator at key community assets. But how sustainable is that? Not only might diesel fuel run-out during a prolonged power outage, but burning diesel also contributes to emissions accelerating climate change. The Environmental Defense Fund argues that linking solar PV to energy storage is more resilient, but can also be more expensive than diesel generators, at least on an upfront capital basis. Again, if we had metrics to measure different grades of resilience, perhaps decision-making by military bases, local governments, and vendors could take a larger, systems view of the problem.

Microgrids are one of the few technology platforms that can provide both mitigation and adaptive services for climate change. In terms of mitigation, microgrids can be designed to reduce carbon emissions by incorporating distributed renewables, thereby shrinking the overall carbon footprint of electricity generation. In terms of adaptive features, microgrids can island (i.e., operate independently of the wider grid), thereby providing emergency power during and in the aftermath of weather-related power outages and fuel supply interruptions.

Next Steps

While the federal and state funding now flowing to microgrids in the name of community resilience is productive, more heavy lifting needs to be done in the regulatory process to assign a reasonable value to the services microgrids provide, especially smart microgrids that incorporate diverse renewable resources into a system that can be justified on economic equations that factor in a much fuller spectrum of public and private benefits.

Perhaps the primary difference between this segment and other microgrid segments is that it is being stimulated by specific government programs that provide funding and regulatory support. In many cases, this is also a necessity for this specific microgrid segment, since these microgrids are plowing new ground in terms of the relationship between distribution utilities and their customers. Ironically, community resilience microgrids garner the widest public support among the tools for making the grid more dynamic and reliable, yet face the largest regulatory barriers. Since they require significantly more buy-in from diverse and often unsophisticated stakeholders, their development cycle is likely longer.

A Threatening Ideal

Furthermore, the ability to finance and finish CRMs on a fully commercial basis would appear to be a very challenging path. Among the challenges facing this microgrid market beyond the lack of metrics for resilience are the following:

- Mixed customer classes that lead to regulatory complexity

- Customer equity issues, especially when utilities are involved with providing CRM services

- Unique financing challenges when addressing community-scale projects

In short, CRMs are an emerging market opportunity still fraught with peril in terms of regulatory issues, rising stakeholder expectations and a lack of clear financial business models. They represent both the epitome of community idealism when it comes to the concept of resilience, as well as the ultimate threat to incumbent utilities. It's one thing to have well-heeled commercial and industrial enterprises investing in their own premium power infrastructure. Quite another situation emerges when entire communities investigate how to become independent in light of disappointments with the service they get from their distribution utilities.

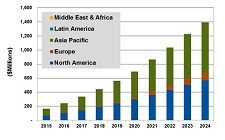

Despite these obstacles, the opportunity is exciting. According to Navigant Research's forthcoming report, Community Resilience Microgrids, worldwide revenues annual revenues from CRMs are expected to grow from $162.9 million annually in 2015 to $1.4 billion by 2024. Though the U.S. leads in terms of policy and technology innovation, the Asia Pacific region is expected to capture the largest market share. By 2024, Asia Pacific is expected to represent roughly half of the total CRM market, largely due to deployments in China and Japan.

Total Community Resilience Microgrid Implementation Revenues, Base Scenario, World Markets: 2015-2024

|

|

Source: Navigant Research |

A Beautiful Model

CRMs may not represent the largest segment of the overall market for distributed energy resources (DER), but they point the way to the future when it comes to addressing the expected growth in DERs in the coming decade. Due to the nascent nature of this market, forecasts of capacity and implementation revenues are speculative. The CRM segment is receiving the most attention from state governments in the U.S., but these systems must also compete against traditional back-up generators and solar PV plus battery nanogrids, both established options for disaster and extreme-weather response. But these approaches have limitations and unfortunate effects, if true community resilience is the goal. The beauty of the microgrid model is that it offers some level of redundancy and contingency in networking assets into a larger system, capturing efficiencies not possible with a single back-up generator powering up a single building.

Revenue growth for CRMs is substantial since they are likely tio grow in complexity over time, and will shift from an early emphasis on aggregating and optimizing existing legacy fossil assets to a more sustainable blend of resources, including solar PV, advanced energy storage, and sophisticated load management technologies that provide value both inside the microgrid and outside the fence. The key for this market is the ability to capture new revenue streams from sales of ancillary services while the grid is up and running to compensate for the lack of assigned vale of resilience benefitsóbenefits that become abundantly obvious when the larger grid goes down, and CRMs are called upon to provide emergency power services.

Navigant Research will examine the future of this important and burgeoning market in a free webinar, "Community Resilience Microgrids," on Tuesday March 17.

About the Author

Peter Asmus is a principal research analyst contributing to

Navigant Research's renewable energy practice, with a focus on

wind energy as well as emerging energy distribution models such

as microgrids and virtual power plants. Asmus has 20 years of

experience in energy and environmental markets, both as a writer

and a research consultant.

© 2015 FierceMarkets, a division of Questex Media Group LLC. All rights reserved.

http://www.smartgridnews.com/story/grid-resilience-what-cost-and-how/2015-03-16