Origin of Antarctica’s eerie Blood Falls

New work confirms zones of liquid salt water hundreds of meters below the bright red waterfall in icy Antarctica, known as Blood Falls.

Blood Falls pouring into Lake Bonney. A tent can be seen in the lower left for size comparison. Photo from the United States Antarctic Program Photo Library.

Blood Falls is a bright red waterfall oozing from Antarctica’s ice. It’s nearly five stories high, in the McMurdo Dry Valley region, one of the coldest and most inhospitable places on Earth, a place scientists like to compare to the cold, dry deserts of Mars. Geomicrobiologist Jill Mikucki, now at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, published what’s still accepted as the best explanation for Blood Falls in 2009. The tests of her team showed that Blood Falls’ waters contained almost no oxygen and hosted a community of at least 17 different types of microorganisms, thought to be flowing from a lake trapped beneath the ice for some 2 million years. Now Mikucki’s work in this area confirms zones of liquid briny water hundreds of meters below Blood Falls. This groundwater network appears to harbor a hidden ecosystem of microbial life, prompting scientists to wonder whether a similar ecosystem could exist on Mars.

Mikucki and her team published their new study in Nature Communications on April 28, 2015. She told the Christian Science Monitor:

We’ve learned so much about the Dry Valleys in Antarctica just by looking at this curiosity.

Blood Falls is not just an anomaly, it’s a portal to this subglacial world.

Researchers suggested in the past that a deep salty groundwater system might lie beneath the Dry Valleys, known for decades to have its own permafrost and above-ground network of small frozen lakes. Mikucki and her colleagues partnered with SkyTEM, a Denmark-based airborne geophysical survey company. They used a helicopter to fly a giant transmitter loop over the Dry Valleys. The loop induced an electrical current in the ground. Then the scientists measured the resistance to the current as far as 350 meters (over 1,000 feet) below the surface.

The video clip below shows the sensor flying over Lake Bonney in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica.

In this way, the researchers identified two distinct zones where there may be concentrated brines (salt water) below Antarctica’s ice.

The scientists say this hidden groundwater might create subsurface links between glaciers, lakes, and possibly even McMurdo Sound, part of the ocean around Antarctica into which the ice of the Dry Valleys continually flows.

The zones of underground water appear to stretch from the Antarctica’s coast to at least 7.5 miles (12 kilometers) inland. The water is thought to be twice as salty as seawater. In fact, Mikucki told the Christian Science Monitor, in her recent study:

Salty water shone like a beacon.

Australian explorer and geologist Griffith Taylor discovered Blood Falls in Antarctica in 1911.

The Falls seep through a crack in what’s now called Taylor Glacier, which flows into Antarctica’s Lake Bonney. Geologists first believed that the color of the water came from algae, but later – thanks to Jill Mikucki’s 2009 study – they accepted that the red color was due to microbes from what had to be a lake hidden beneath Taylor Glacier. Lake water trickles out at the glacier’s end and deposits an orange stain across the ice as its iron-rich waters rust on contact with air.

How can the microbes that color Blood Falls survive underground, with no light or oxygen? According to a 2009 story in ScienceNow from the AAAS:

Mikucki and her team uncovered three main clues. First, a genetic analysis of the microbes showed that they were closely related to other microorganisms that use sulfate instead of oxygen for respiration. Second, isotopic analysis of sulfate’s oxygen molecules revealed that the microbes were modifying sulfate in some form but not using it directly for respiration. Third, the water was enriched with soluble ferrous iron, which would happen only if the organisms had converted ferric iron, which is insoluble, to the soluble ferrous form. The best explanation … is that the organisms use sulfate as a catalyst to ‘breathe’ with ferric iron and metabolize the limited amounts of organic matter trapped with them years ago. Lab experiments [had] suggested this might be possible, but it [had] never been observed in a natural environment.

Read Mikucki and colleagues’ 2009 paper, explaining Blood Falls’ red color, in the journal Science

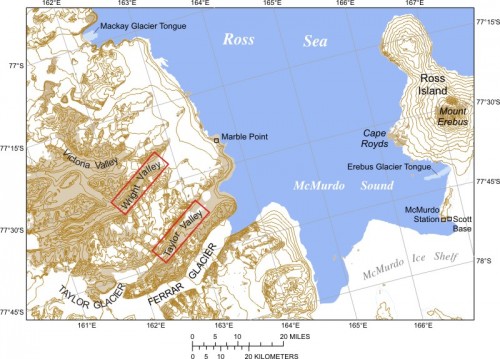

Dry Valleys and McMurdo Sound, via Wikimedia Commons and USGS

False-color image of Taylor Glacier, flowing into Lake Bonney in Antarctica. Blood Falls is on the left side of both photos. Image acquired by NASA’s Terra satellite on November 29, 2000. Read more about this image from NASA’s Earth Observatory.

The image above is a wider view, via satellite, of the area in Antarctica where Taylor Glacier and its Blood Falls flow into Lake Bonney.

This region – the McMurdo Dry Valleys – is a series of parallel valleys between the Ross Sea and the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. Note the lack of snow on the surface. A nearly relentless katabatic wind — cold, dry air that rolls downhill toward the sea from the high altitudes of the ice sheet – sweeps the ground free of snow and ice.

There are many ice-covered lakes on the surface of the Dry Valleys. Each is chemically different from the others. Geologists who work in Antartica have studied for years to try to understand how the lakes formed and why they evolved so differently through time.

Now they will be trying to understand more about the hidden groundwater – and the ecosystem it must contain – revealed by the presence of Blood Falls.

Bottom line: The red color of Blood Falls in Antarctica was known to be caused by microbes living off sulfur and iron in what was surmised to be oxygen-free water trapped beneath the ice for nearly 2 million years. Recent work by Jill Mikucki at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, confirms that there are indeed zones of liquid briny water hundreds of meters below Blood Falls, likely harboring a hidden ecosystem of microbial life.

Via Science and Christian Science Monitor.

© 2014 Earthsky Communications Inc

http://earthsky.org/earth/blood-falls-five-stories-high-seeps-from-an-antarctic-glacier