Standing Strong for Chief Standing Bear, A Native Hero

The route of the Ponca Tribe’s forced march from Nebraska to Oklahoma in 1877 could soon be designated a National Historic Trail, thanks in part to students at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

The little-known trail is important not only because it retraces yet another devastating removal of Indigenous Peoples from their homeland under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1834, but also because the ruling in a lawsuit resulting from the march was the first time the U.S. legally recognized American Indians as persons. Nebraska and Kansas have passed resolutions supporting the designation; Oklahoma will vote this month on its resolution.

The Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs has been spearheading the effort, in consultation with the Ponca tribes. Executive Director Judi gaiashkibos, Ponca Tribe of Nebraska, says, “The Standing Bear Trail [federal] legislation represents a major step towards national recognition of this important civil rights story. It has been the focus of the work of many people who believe as I do that Chief Standing Bear is an American hero. It is time to tell this story.”

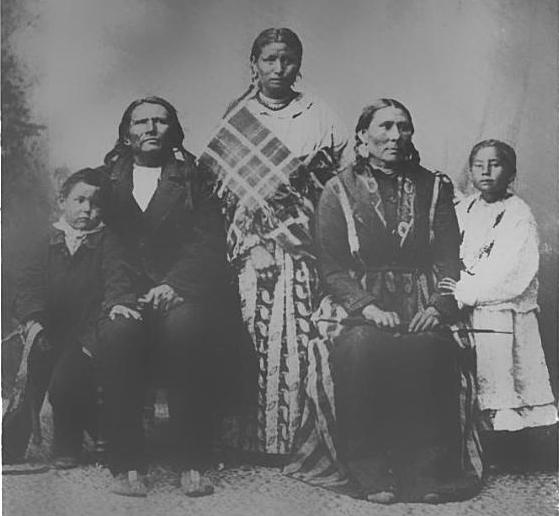

Until the late 19th century, the Ponca Tribe’s homeland was situated between the Missouri and the Niobara rivers in Nebraska and South Dakota. The tribe had ceded most of its land to the U.S. by the mid 1860s, ending up on a reservation near the Niobara.

The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie mistakenly included the Ponca land in the Great Sioux Reservation, forcing the tribe in 1875 to agree to move to “Indian Territory.”

Ten Ponca chiefs went to what would later become Oklahoma to select the land the tribe would occupy but returned to Nebraska on foot after refusing to agree their people would live on the malaria-infested land they were offered. Standing Bear was one of the chiefs who returned “weary and footsore and sick at heart,” according to a letter he sent to the Sioux City Daily Journal.

In 1877, U.S. soldiers force-marched 523 Ponca along the 600-mile Ponca Trail of Tears to their new disease-ridden reservation. Nine people, including Standing Bear’s daughter, died along the way. Two years after relocation, a third of the tribe, Standing Bear’s son Bear Shield among them, had died.

Standing Bear had promised his son that he would take his body home for burial. He and 26 others left for Nebraska in January 1879. Alerted that the Ponca had left their reservation without permission, the Interior Secretary sent General George Crook to arrest them.

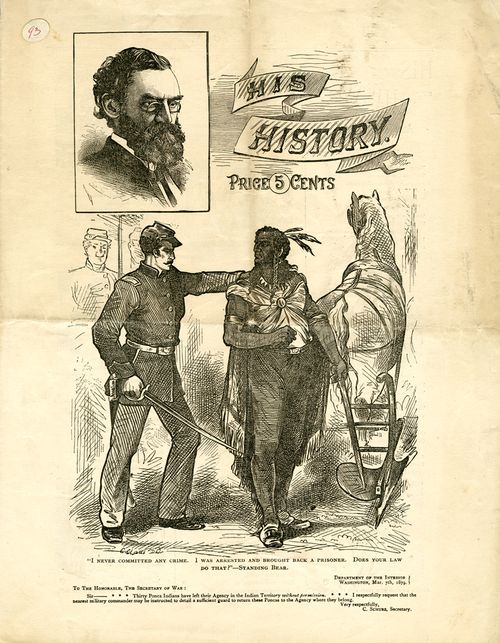

Crook, however, also arranged for Standing Bear to meet with minister and abolitionist Thomas Henry Tibbles, then an editor of the Omaha Herald. Tibbles published an account of the Poncas’ situation and hired two lawyers to represent them after Crook recommended that they seek a writ of habeus corpus. Nebraska District Court Judge Elmer Scipio Dundy issued the writ, saying that Standing Bear should be released and allowed to return to his land.

The trial to determine whether Standing Bear had been illegally arrested and detained started on May 1, 1879, over the objections of the Indian Affairs Commissioner. Standing Bear’s lawyers argued that he had the protections guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

According to a contemporary account by Tibbles, Standing Bear addressed the court, extending his hand toward the judge's bench. “That hand is not the color of yours, but if I pierce it, I shall feel pain. If you pierce your hand, you also feel pain. The blood that will flow from mine will be the same color as yours. I am a man. God made us both,” he said.

Judge Dundy ruled on May 12, “An Indian is a ‘person’ within the meaning of the laws of the United States, and has, therefore, the right to sue out a writ of habeas corpus in a federal court, or before a federal judge, in all cases where he may be confined or in custody under color of authority of the United States, or where he is restrained of liberty in violation of the constitution or laws of the United States.” Standing Bear was released and allowed to go home.

This was the first time a U.S. court had recognized an Indian as a person with equal protection under the law. It would be nearly another half century before American Indians were recognized as citizens of the U.S.

RELATED: Native History: Court Rules an Indian Is a Man With Rights

The NCIA enlisted the help of students in Andy Jewell’s Digital Humanities Practicum at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln to create a digital map of the trail integrated with historical documents to help convince Congress to fund a feasibility study for the historic trail designation.

“The Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs challenged the students to think about ways to make information about the trail more available,” Jewell said. The result is a multi-layered map now available on the commission’s website.

The commission’s Alicia Harris, Fort Peck Assiniboine, says, “The map has newspaper articles from the time period, quotations from the journal for the Indian agent, contemporary documents and historical documents” all in one place.

“We created a deep map that included pictures and videos and text to help tell the story,” says Nora Greiman, one of four students who worked on the project.

The Ponca now comprise two federally-recognized entities, the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska and the Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma. The 3,770-member landless Nebraska tribe is headquartered in Niobara. The 3,600-member Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma is headquartered in Ponca City.

The U.S. House passed legislation to fund the feasibility study in late April. It now goes to the Senate. Oklahoma Rep. Tom Cole, Chickasaw, was a cosponsor. He said in a news release, “Chief Standing Bear’s unwavering fight to secure equal treatment under the law for America’s Native people has helped pave the way for many more remarkable achievements by Native Americans across America. Designating a trail in his memory would rightly honor his memory, secure his legacy and inspire generations to come.”

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/05/20/standing-strong-chief-standing-bear-native-hero-160411